Amphibian “apocalypse” caused by most destructive pathogen ever – Chytrid fungi have caused extinctions and declines in at least 501 frog and salamander species

By Michael Greshko

28 March 2019

(National Geographic) – For decades, a silent killer has slaughtered frogs and salamanders around the world by eating their skins alive. Now, a global team of 41 scientists has announced that the pathogen—which humans unwittingly spread around the world—has damaged global biodiversity more than any other disease ever recorded.

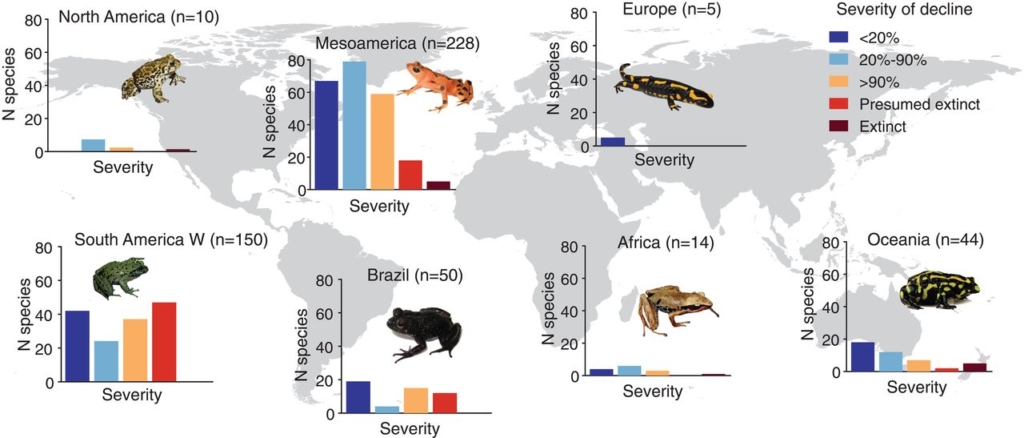

The new study, published in Science on Thursday, is the first comprehensive tally of the damage done by the chytrid fungi Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd) and Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal). In all, the fungi have driven the declines of at least 501 amphibian species, or about one out of every 16 known to science.

Of the chytrid-stricken species, 90 have gone extinct or are presumed extinct in the wild. Another 124 species have declined in number by more than 90 percent. All but one of the 501 declines was caused by Bd.

“We’ve known that’s chytrid’s really bad, but we didn’t know how bad it was, and it’s much worse than the previous early estimates,” says study leader Ben Scheele, an ecologist at Australian National University. “Our new results put it on the same scale, in terms of damage to biodiversity, as rats, cats, and [other] invasive species.”

Scheele has seen the fungus’s carnage firsthand. At one of his field sites in Australia, an extended El Niño fueled mass frog breeding and dispersal—letting Bd spread as never before. Before the fungus, populations of the alpine tree frog were so abundant there, he had to watch his step when he went out at night. Now, the species is nearly impossible to find.

Saddened and shocked, Scheele resolved to put numbers to the decline. Four years—and innumerable email conversations—later, Scheele’s team has finally combined all known reports of chytrid declines into a single consistent database, revealing Bd and Bsal‘s record-breaking toll.

“Chytrid fungus is the most destructive pathogen ever described by science—that’s a pretty shocking realization,” adds Wendy Palen, a biologist at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia who wrote about the study for Science. [more]

Amphibian ‘apocalypse’ caused by most destructive pathogen ever

Mass amphibian extinctions globally caused by fungal disease

29 March 2019 (ANU) – An international study led by ANU has found a fungal disease has caused dramatic population declines in more than 500 amphibian species, including 90 extinctions, over the past 50 years.

The disease, which eats away at the skin of amphibians, has completely wiped out some species, while causing more sporadic deaths among other species. Amphibians, which live part of their life in water and the other part on land, mainly consist of frogs, toads and salamanders.

The deadly disease, chytridiomycosis, is present in more than 60 countries – the worst affected parts of the world are Australia, Central America and South America.

Lead researcher Dr Ben Scheele said the team found that chytridiomycosis is responsible for the greatest loss of biodiversity due to a disease.

“The disease is caused by chytrid fungus, which likely originated in Asia where local amphibians appear to have resistance to the disease,” said Dr Scheele from the Fenner School of Environment and Society at ANU.

He said the unprecedented number of declines places chytrid fungus among the most damaging of invasive species worldwide – similar to rats and cats in terms of the number of species each of them endangers.

“Highly virulent wildlife diseases, including chytridiomycosis, are contributing to the Earth’s sixth mass extinction,” Dr Scheele said.

“The disease we studied has caused mass amphibian extinctions worldwide. We’ve lost some really amazing species.”

Dr Scheele said more than 40 frog species in Australia had declined due to the fungal disease during the past 30 years, including seven species that had become extinct.

“Globalisation and wildlife trade are the main causes of this global pandemic and are enabling the spread of disease to continue,” he said.

“Humans are moving plants and animals around the world at an increasingly rapid rate, introducing pathogens into new areas.”

Dr Scheele said improved biosecurity and wildlife trade regulation were urgently needed to prevent any more extinctions around the world.

“We’ve got to do everything possible to stop future pandemics, by having better control over wildlife trade around the world.”

Dr Scheele said the team’s work identified that many species were still at high risk of extinction over the next 10-20 years from chytridiomycosis due to ongoing declines.

“Knowing what species are at risk can help target future research to develop conservation actions to prevent extinctions.”

Dr Scheele said conservation programs in Australia had prevented the extinction of frog species and developed new reintroduction techniques to save some amphibian species.

“It’s really hard to remove chytrid fungus from an ecosystem – if it is in an ecosystem, it’s pretty much there to stay unfortunately. This is partly because some species aren’t killed by the disease,” he said.

“On the one hand, it’s lucky that some species are resistant to chytrid fungus; but on the other hand, it means that these species carry the fungus and act as a reservoir for it so there’s a constant source of the fungus in the environment.

Co-researcher Dr Claire Foster, who is also from the Fenner School of Environment and Society, said the ANU-led study involved close collaboration with Professor Frank Pasmans and Dr Stefano Canessa at the University of Ghent, Belgium, alongside 38 different amphibian and wildlife disease experts from around the world.

“These collaborators enabled us to get first-hand insight into what has been happening on the ground in those countries,” she said.

The study is published in Science and was supported by the Threatened Species Recovery Hub of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program: http://science.sciencemag.org/cgi/doi/10.1126/science.aav0379.

Mass amphibian extinctions globally caused by fungal disease

Amphibian fungal panzootic causes catastrophic and ongoing loss of biodiversity

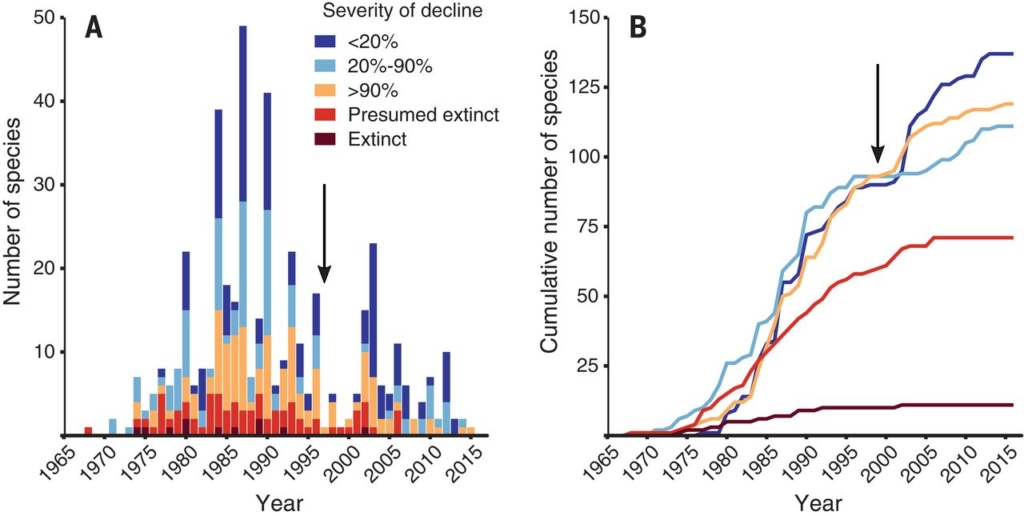

ABSTRACT: Anthropogenic trade and development have broken down dispersal barriers, facilitating the spread of diseases that threaten Earth’s biodiversity. We present a global, quantitative assessment of the amphibian chytridiomycosis panzootic, one of the most impactful examples of disease spread, and demonstrate its role in the decline of at least 501 amphibian species over the past half-century, including 90 presumed extinctions. The effects of chytridiomycosis have been greatest in large-bodied, range-restricted anurans in wet climates in the Americas and Australia. Declines peaked in the 1980s, and only 12% of declined species show signs of recovery, whereas 39% are experiencing ongoing decline. There is risk of further chytridiomycosis outbreaks in new areas. The chytridiomycosis panzootic represents the greatest recorded loss of biodiversity attributable to a disease.

SIGNIFICANCE: The demise of amphibians? Rapid spread of disease is a hazard in our interconnected world. The chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis was identified in amphibian populations about 20 years ago and has caused death and species extinction at a global scale. Scheele. et al., found that the fungus has caused declines in amphibian populations everywhere except at its origin in Asia (see the Perspective by Greenberg and Palen). A majority of species and populations are still experiencing decline, but there is evidence of limited recovery in some species. The analysis also suggests some conditions that predict resilience.

Amphibian fungal panzootic causes catastrophic and ongoing loss of biodiversity