Arctic boreal forests burning at ‘unprecedented’ rate

By Andrew Freedman

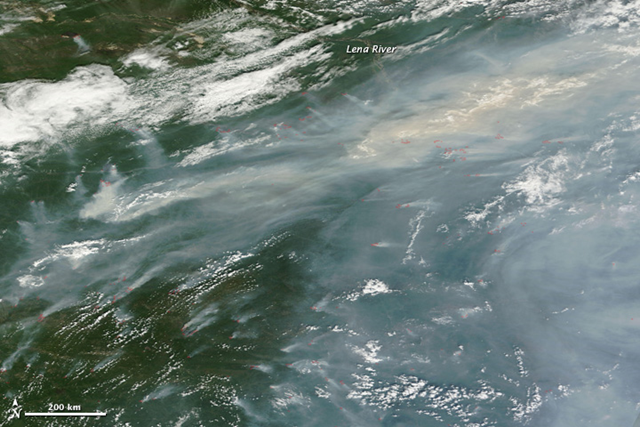

22 July 2013 (Climate Central) – In a sign of how swiftly and extensively climate change is reshaping the Arctic environment, a new study has found that the region’s mighty boreal forests — stands of mighty spruce, fir, and larch trees that serve as the gateway to the Arctic Circle — have been burning at an unprecedented rate during the past few decades. The study, published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that the boreal forests have not burned at today’s high rates for at least the past 10,000 years, and climate change projections show even more wildfire activity may be to come. The study links the increase in fire activity to increased temperatures and drier conditions in the region, which is driving wholesale changes in the massive forests that encircle the northern portion of the globe. Wildfire activity in the boreal forest biome, which is also known as taiga, plays a crucial role in the globe’s carbon budget, since these forests represent nearly 10 percent of the planet’s land surface and contain more than 30 percent of the carbon that is stored on land, in plants and soils. Globally, the boreal forest covers 6.41 million square miles, forming a ring along and just below the Arctic Circle. Increased burning in recent years has meant that more stored carbon has been freed from these ecosystems, which acts as a feedback, leading to more global warming, and hence more wildfires. In addition, the black carbon, or soot, emitted from the fires can land on snow and ice in the Arctic, hastening melting. Alaska has seen a significant increase in wildfire activity in recent years, which has been linked to the effects of a warming climate, including warmer, drier summers with greater thunderstorm activity. So far this year, Alaska has seen 451 wildfires (not all of them in the boreal forest), which have burned 1.3 million acres, the most of any state in the country. The new study found that while global warming is likely to lead to even greater wildfire activity in the coming decades, vegetation changes as a result of such fires may keep a lid on the magnitude of the surge in wildfire activity, as apparently occurred during the so-called “Medieval Warm Period” between about 800 to 1400 AD. For the study, researchers used charcoal records from 14 lakes in the Yukon Flats of interior Alaska, which is one of the most flammable parts of the boreal forest biome, to infer changes in the wildfire regime during the past 10,000 years. Scientists employ charcoal records as a “proxy” indicator of past wildfire activity, in much the same way that other climate researchers have used tree rings to study drought history. The researchers found that recent wildfire activity exceeded the range of natural variability during the past 10,000 years, which they attributed to climatic warming during the past few decades and “the legacy effect” of the Little Ice Age, which occurred from about 1350 to 1850 AD, and brought cold and wet conditions to Alaska that encouraged the growth of trees and plants in the boreal forests. Such vegetation is now serving as fuel for wildfires. “The ecosystems in this ecoregion appear to be undergoing a transition that is unprecedented” in the past 10,000 years, said Feng Sheng Hu, a coauthor of the study and a plant biologist at the University of Illinois. “We think this transition may occur in other boreal regions in the decades to come,” he said via email. [more]

Arctic’s Boreal Forests Burning At ‘Unprecedented’ Rate