Report revels 56 percent of UK species have declined since 1970 and 1,199 species are threatened with extinction

By Dr. Barnaby Smith

14 September 2016 (CEH) – The State of Nature 2016 UK report is launched by Sir David Attenborough and UK conservation and research organisations at the Royal Society in London this morning (Wednesday, September 14). Following on from the first State of Nature report published in 2013 the report reveals that over half (56%) of UK species studied have declined since 1970, while more than one in ten (1,199 species) of the nearly 8000 species assessed in the UK are under threat of disappearing from our shores altogether. The State of Nature Partnership is led by RSPB and is made up of 53 organisations, comprising conservation charities, biological recording schemes and societies, and a small number of research organisations including the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (CEH). The partnership has pooled expertise and knowledge to present the clearest picture to date of the status of the UK’s native species across land and sea. CEH has contributed two large datasets to the 2016 report: long term trends for 1,300 plants from the Countryside Survey which we’ve run since 1978, and annual indices of status for 1,600 species from the Biological Records Centre (BRC). CEH also contributed long term population trends in 60 butterfly species from the UK Butterfly Monitoring Scheme, which is run as a partnership with Butterfly Conservation. Together, these datasets make up around 75% of the 3,816 species on which the State of Nature 2016 analysis are based. Sir David Attenborough said, “The rallying call issued after the State of Nature report in 2013 has promoted exciting and innovative conservation projects. Landscapes are being restored, special places defended, struggling species being saved and brought back. But we need to build significantly on this progress if we are to provide a bright future for nature and for people. The future of nature is under threat and we must work together; Governments, conservationists, businesses and individuals, to help it. Millions of people in the UK care very passionately about nature and the environment and I believe that we can work together to turn around the fortunes of wildlife.”

Dr Isaac added, “We’re working now to make our analyses more suitable for rare species and under-recorded taxonomic groups, so that the next State of Nature report, hopefully out in 2019, will cover the status of a much broader set of species and is increasingly representative of UK biodiversity.” The report reveals that since 2002 more than half (53%) of UK species studied have declined and there is little evidence to suggest that the rate of loss is slowing down. In order to reduce the impact we are having on our wildlife, and to help struggling species, we needed to understand what’s causing these declines. Using evidence from the last 50 years, the report states that significant and ongoing changes in agricultural practices are having the single biggest impact on nature. The report highlights many inspiring examples of conservation action that is helping to turn the tide. From pioneering science that has revealed for the first time the reasons why nature is changing in the UK, to conservation work – such as the reintroductions of the pine marten and large blue butterfly (which was led by CEH scientists), and the restoration of areas of our uplands, meadows and coastal habitats. Mark Eaton from the RSPB, lead author on the report, said, “Never before have we known this much about the state of UK nature and the threats it is facing. Since the 2013, the partnership and many landowners have used this knowledge to underpin some amazing scientific and conservation work. But more is needed to put nature back where it belongs – we must continue to work to help restore our land and sea for wildlife. Of course, this report wouldn’t have been possible without the army of dedicated volunteers who brave all conditions to survey the UK’s wildlife. Knowledge is the most essential tool that a conservationist can have, and without their efforts, our knowledge would be significantly poorer.” [more]

UK State of Nature 2016 report

- Between 1970 and 2013, 56% of species declined, with 40% showing strong or moderate declines. 44% of species increased, with 29% showing strong or moderate increases. Between 2002 and 2013, 53% of species declined and 47% increased. These measures were based on quantitative trends for almost 4,000 terrestrial and freshwater species in the UK.

- Of the nearly 8,000 species assessed using modern Red List criteria, 15% are extinct or threatened with extinction from Great Britain.

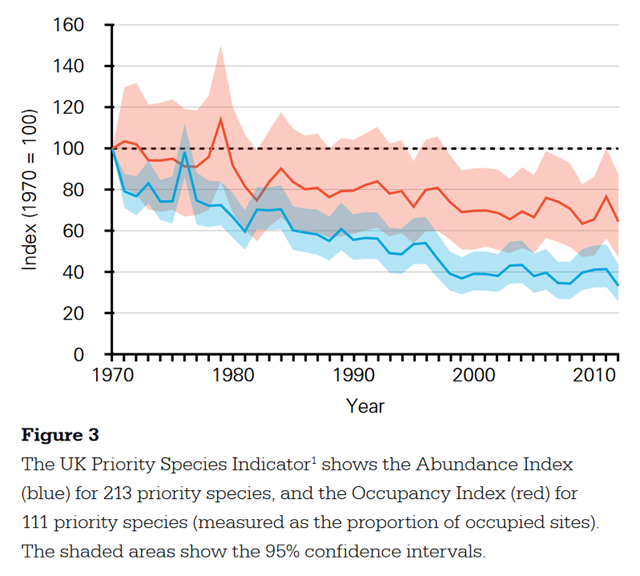

- An index of species’ status, based on abundance and occupancy data, has fallen by 16% since 1970. Between 2002 and 2013, the index fell by 3%. This is based on data for 2,501 terrestrial and freshwater species in the UK.

- An index describing the population trends of species of special conservation concern in the UK has fallen by 67% since 1970, and by 12% between 2002 and 2013. This is based on trend information for 213 priority species.

- A new measure that assesses how intact a country’s biodiversity is, suggests that the UK has lost significantly more nature over the long term than the global average. The index suggests that we are among the most nature-depleted countries in the world.

- The loss of nature in the UK continues. Although many short-term trends suggest improvement, there was no statistical difference between our long and short-term measures of species’ change, and no change in the proportion of species threatened with extinction.

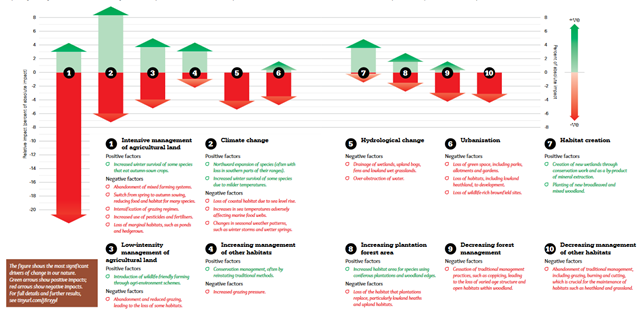

- Many factors have resulted in changes to the UK’s wildlife over recent decades, but policy-driven agricultural change was by far the most significant driver of declines. Climate change has had a significant impact too, although its impact has been mixed, with both beneficial and detrimental effects on species. Nevertheless, we know that climate change is one of the greatest long-term threats to nature globally.

- Well-planned conservation projects can turn around the fortunes of wildlife. This report gives examples of how governments, non-governmental organisations, businesses, communities and individuals have worked together to bring nature back.

- We have a moral obligation to save nature and this is a view shared by the millions of supporters of conservation organisations across the UK. Not only that, we must save nature for our own sake, as it provides us with essential and irreplaceable benefits that support our welfare and livelihoods. [more]

Pictures of a depauparate country:

http://witsendnj.blogspot.com/2016/09/the-waste-land.html