Balkan wildlife faces extinction threat from border fence to control migrants

By Arthur Neslen

11 August 2016 Ljubljana, the Upper Kolpa valley, and Zagreb (Guardian) – The death toll of animals killed by a razor wire fence designed to stop migrants crossing into Europe is mounting, amid warnings that bears, lynx, and wolves could become locally extinct if the barrier is completed and consolidated. The rising tally of dead roe and red deer is still mercifully small, but contested by local people who claim that it is being systematically under-counted. Slovenia began erecting the barrier across 180km of its river border with Croatia last winter, as a temporary measure to staunch the flow of asylum seekers, mostly from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan. Inadvertently, it has also created a huge obstacle to animals freely moving across the border in a wildlife rich corner of Europe. But even though the human migration crisis has dramatically eased, Slovenia’s interior ministry is seeking a change in the law to prevent environmental factors from slowing the barrier’s extension. A government spokesperson said that while refugee numbers were falling, “there are still more than 57,000 migrants in Greece. The situation in Turkey remains very uncertain after the military coup. There is a political crisis in Macedonia, and an increasing number of migrants are gathering in Serbia, which lacks sufficient accommodation capacities. Also, the number of people travelling the migrant route across the Mediterranean to Italy has increased again.” While the fence is supposed to be a temporary measure, fears that the crisis could be prolonged were heightened when the government signalled its intent to fence its entire 670km border with Croatia in December. […] Geographical isolation would throw the continued survival of the region’s 10 wolf packs into doubt, disrupting centuries-old mating migration routes, according to a peer-reviewed paper published in the journal PLOS Biology. Other carnivores could fare even worse. “For the Dinaric lynx, the construction of the razor wire fence may just be the last push for the population to spiral down the extinction vortex,” the study’s authors said. The mountain cat was only reintroduced to the Dinaric mountain chain in 1973, after human activity wiped it out. [more]

Balkan wildlife faces extinction threat from border fence to control migrants

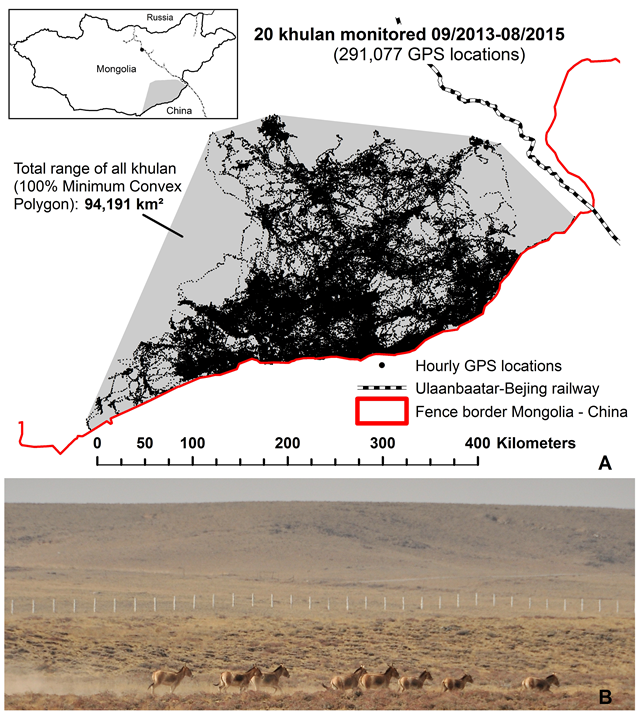

ABSTRACT: The ongoing refugee crisis in Europe has seen many countries rush to construct border security fencing to divert or control the flow of people. This follows a trend of border fence construction across Eurasia during the post-9/11 era. This development has gone largely unnoticed by conservation biologists during an era in which, ironically, transboundary cooperation has emerged as a conservation paradigm. These fences represent a major threat to wildlife because they can cause mortality, obstruct access to seasonally important resources, and reduce effective population size. We summarise the extent of the issue and propose concrete mitigation measures.

Border Security Fencing and Wildlife: The End of the Transboundary Paradigm in Eurasia?

The SOLUTION to all these human caused problems is FEWER HUMANS.

If we followed that rule long enough and widely enough, we would have finally addressed the root causes that we can't seem to solve.

Wildlife Dying En Masse As South American Rivers Dry UP

"The SOLUTION to all these human caused problems is FEWER HUMANS." Could not agree more!