Effects of human carbon emissions could last 10,000 years – ‘Our greenhouse gas emissions today produce climate-change commitments for many centuries to millennia’

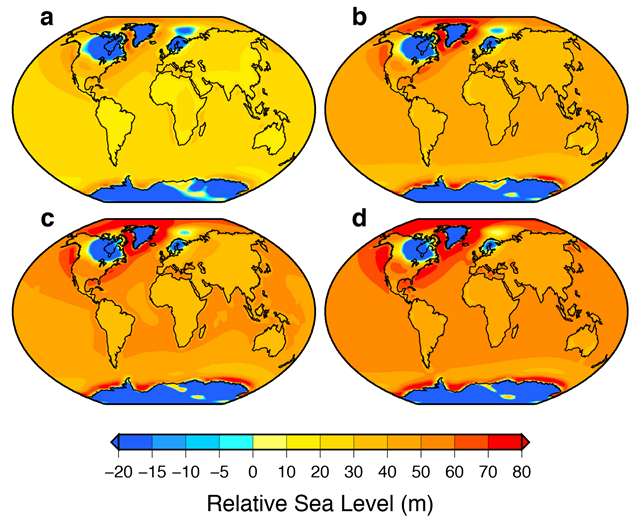

CORVALLIS, Oregon, 8 February 2016 (OSU) – At the rate humans are emitting carbon into the atmosphere, the Earth may suffer irreparable damage that could last tens of thousands of years, according to a new analysis published this week. Too much of the climate change policy debate has focused on observations of the past 150 years and their impact on global warming and sea level rise by the end of this century, the authors say. Instead, policy-makers and the public should also be considering the longer-term impacts of climate change. “Much of the carbon we are putting in the air from burning fossil fuels will stay there for thousands of years – and some of it will be there for more than 100,000 years,” said Peter Clark, an Oregon State University paleoclimatologist and lead author on the article. “People need to understand that the effects of climate change on the planet won’t go away, at least not for thousands of generations.” The researchers’ analysis is being published this week in the journal Nature Climate Change. Thomas Stocker of the University of Bern in Switzerland, who is past-co-chair of the IPCC’s Working Group I, said the focus on climate change at the end of the 21st century needs to be shifted toward a much longer-term perspective. “Our greenhouse gas emissions today produce climate-change commitments for many centuries to millennia,” said Stocker, a climate modeler and co-author on the Nature Climate Change article. “It is high time that this essential irreversibility is placed into the focus of policy-makers. “The long-term view sends the chilling message (about) what the real risks and consequences are of the fossil fuel era,” Stocker added. “It will commit us to massive adaptation efforts so that for many, dislocation and migration becomes the only option.” Sea level rise is one of the most compelling impacts of global warming, yet its effects are just starting to be seen. The latest IPCC report, for example, calls for sea level rise of just one meter by the year 2100. In their analysis, however, the authors look at four difference sea level-rise scenarios based on different rates of warming, from a low end that could only be reached with massive efforts to eliminate fossil fuel use over the next few decades, to a higher rate based on the consumption of half the remaining fossil fuels over the next few centuries. With just two degrees (Celsius) warming in the low-end scenario, sea levels are predicted to eventually rise by about 25 meters. With seven degrees warming at the high-end scenario, the rise is estimated at 50 meters, although over a period of several centuries to millennia. “It takes sea level rise a very long time to react – on the order of centuries,” Clark said. “It’s like heating a pot of water on the stove; it doesn’t boil for quite a while after the heat is turned on – but then it will continue to boil as long as the heat persists. Once carbon is in the atmosphere, it will stay there for tens or hundreds of thousands of years, and the warming, as well as the higher seas, will remain.” Clark said for the low-end scenario, an estimated 122 countries have at least 10 percent of their population in areas that will be directly affected by rising sea levels, and that some 1.3 billion – or 20 percent of the global population – live on lands that may be directly affected. The impacts become greater as the warming and sea level rise increases. “We can’t keep building seawalls that are 25 meters high,” noted Clark, a professor in OSU’s College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences. “Entire populations of cities will eventually have to move.” Daniel Schrag, the Sturgis Hooper Professor of Geology at Harvard University, said there are moral questions about “what kind of environment we are passing along to future generations.” “Sea level rise may not seem like such a big deal today, but we are making choices that will affect our grandchildren’s grandchildren – and beyond,” said Schrag, a co-author on the analysis and director of Harvard’s Center for the Environment. “We need to think carefully about the long time-scales of what we are unleashing.” The new paper makes the fundamental point that considering the long time scales of the carbon cycle and of climate change means that reducing emissions slightly or even significantly is not sufficient. “To spare future generations from the worst impacts of climate change, the target must be zero – or even negative carbon emissions – as soon as possible,” Clark said. “Taking the first steps is important, but it is essential to see these as the start of a path toward total decarbonization,” Schrag pointed out. “This means continuing to invest in innovation that can someday replace fossil fuels altogether. Partial reductions are not going to do the job.” Stocker said that in the last 50 years alone, humans have changed the climate on a global scale, initiating the Anthropocene, a new geological era with fundamentally altered living conditions for the next many thousands of years. “Because we do not know to what extent adaptation will be possible for humans and ecosystems, all our efforts must focus on a rapid and complete decarbonization –the only option to limit climate change,” Stocker said. The researchers’ work was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Energy, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the German Science Foundation and the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Scientists say window to reduce carbon emissions is small

ABSTRACT: Most of the policy debate surrounding the actions needed to mitigate and adapt to anthropogenic climate change has been framed by observations of the past 150 years as well as climate and sea-level projections for the twenty-first century. The focus on this 250-year window, however, obscures some of the most profound problems associated with climate change. Here, we argue that the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, a period during which the overwhelming majority of human-caused carbon emissions are likely to occur, need to be placed into a long-term context that includes the past 20 millennia, when the last Ice Age ended and human civilization developed, and the next ten millennia, over which time the projected impacts of anthropogenic climate change will grow and persist. This long-term perspective illustrates that policy decisions made in the next few years to decades will have profound impacts on global climate, ecosystems and human societies — not just for this century, but for the next ten millennia and beyond.

Consequences of twenty-first-century policy for multi-millennial climate and sea-level change