Fish stocks declining worldwide as phytoplankton at base of food web die off

By Clare Leschin-Hoar

14 December 2015 (NPR) – For anyone paying attention, it’s no secret there’s a lot of weird stuff going on in the oceans right now. We’ve got a monster El Nino looming in the Pacific. Ocean acidification is prompting hand wringing among oyster lovers. Migrating fish populations have caused tensions between countries over fishing rights. And fishermen say they’re seeing unusual patterns in fish stocks they haven’t seen before. Researchers now have more grim news to add to the mix. An analysis published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences finds that the ability of fish populations to reproduce and replenish themselves is declining across the globe. “This, as far as we know, is the first global-scale study that documents the actual productivity of fish stocks is in decline,” says lead author Gregory L. Britten, a doctoral student at the University of California, Irvine. Britten and some fellow researchers looked at data from a global database of 262 commercial fish stocks in dozens of large marine ecosystems across the globe. They say they’ve identified a pattern of decline in juvenile fish (young fish that have not yet reached reproductive age) that is closely tied to a decline in the amount of phytoplankton, or microalgae, in the water. “We think it is a lack of food availability for these small fish,” says Britten. “When fish are young, their primary food is phytoplankton and microscopic animals. If they don’t find food in a matter of days, they can die.” The worst news comes from the North Atlantic, where the vast majority of species, including Atlantic cod, European and American plaice, and sole are declining. In this case, Britten says historically heavy fishing may also play a role. Large fish, able to produce the biggest, most robust eggs, are harvested from the water. At the same time, documented declines of phytoplankton made it much more difficult for those fish stocks to bounce back when they did reproduce, despite aggressive fishery management efforts, says Britten.[more]

Fish Stocks Are Declining Worldwide, And Climate Change Is On The Hook

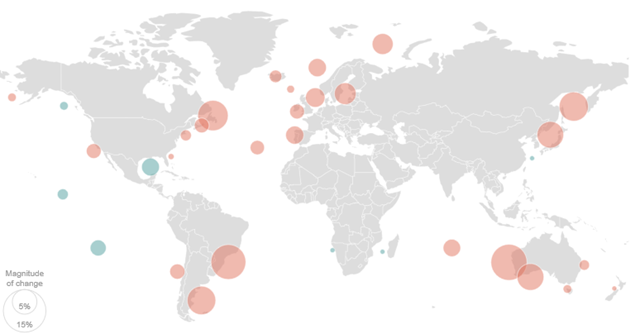

ABSTRACT: Marine fish and invertebrates are shifting their regional and global distributions in response to climate change, but it is unclear whether their productivity is being affected as well. Here we tested for time-varying trends in biological productivity parameters across 262 fish stocks of 127 species in 39 large marine ecosystems and high-seas areas (hereafter LMEs). This global meta-analysis revealed widespread changes in the relationship between spawning stock size and the production of juvenile offspring (recruitment), suggesting fundamental biological change in fish stock productivity at early life stages. Across regions, we estimate that average recruitment capacity has declined at a rate approximately equal to 3% of the historical maximum per decade. However, we observed large variability among stocks and regions; for example, highly negative trends in the North Atlantic contrast with more neutral patterns in the North Pacific. The extent of biological change in each LME was significantly related to observed changes in phytoplankton chlorophyll concentration and the intensity of historical overfishing in that ecosystem. We conclude that both environmental changes and chronic overfishing have already affected the productive capacity of many stocks at the recruitment stage of the life cycle. These results provide a baseline for ecosystem-based fisheries management and may help adjust expectations for future food production from the oceans.

Freshwater scarcity also appears to worsen rapidly prior to two degrees warming, and worsen more slowly after. The ruining of crop land appears to slow down around 3 degrees of warming, after significant damage, as indicated by the steep upward slope of the red line, has already been done. The same holds true for damage to UNESCO World Heritage sites.

The paper also does away with another common trope: that as the effects of climate change get worse, governments will feel more and more pressure to do something about it, like dramatically reduce emissions. But, Caldeira says, the opposite is probably true. “Once all the sensitive components of our planet are already damaged, incentive to decrease emissions may decrease…. The incentive to avoid climate change may be greatest before we have done substantial damage.”