Amazon drought caused doubling of tree mortality, reduced carbon sink by 1.4 billion tons of CO2

(RTCC) – Severe drought five years ago caused an observed doubling in the rate of tree mortality in the Amazon rainforest, according to a study published in the journal Nature on Wednesday, 4 March 2015. In addition, the drought caused the forest to take up about 1.4 billion tonnes less carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The Amazon forest acts as a carbon sink, because trees suck the greenhouse gas CO2 out of the atmosphere as they grow, during photosynthesis, converting this to plant matter including bark, wood and roots. The Nature article showed how droughts may disrupt this carbon sink, both as a result of reduced photosynthesis and tree die-back. The study may be a concern, if climate change in future caused more frequent, severe droughts. The main finding of the study was that trees still grew even during a severe drought, but that was at the expense of using energy for tissue maintenance, defence and putting aside sugars against future stresses. Weakened maintenance may have contributed to greater death tree mortality observed in the years following the drought, the authors said.They found that rates of tree mortality at least doubled in the drought-affected areas, to 4-7%, from a long-term trend of 1.6%. “Our data indicate that mortality rates peaked one to two years after the drought, consistent with the hypothesis that trees were weakened during the drought from decreased maintenance but only succumbed later.” [more]

Amazon drought led to doubling of tree mortality

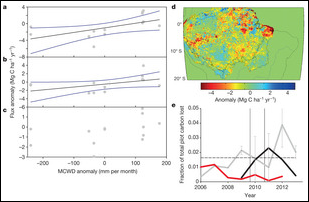

ABSTRACT: In 2005 and 2010 the Amazon basin experienced two strong droughts1, driven by shifts in the tropical hydrological regime2 possibly associated with global climate change3, as predicted by some global models3. Tree mortality increased after the 2005 drought4, and regional atmospheric inversion modelling showed basin-wide decreases in CO2 uptake in 2010 compared with 2011 (ref. 5). But the response of tropical forest carbon cycling to these droughts is not fully understood and there has been no detailed multi-site investigation in situ. Here we use several years of data from a network of thirteen 1-ha forest plots spread throughout South America, where each component of net primary production (NPP), autotrophic respiration and heterotrophic respiration is measured separately, to develop a better mechanistic understanding of the impact of the 2010 drought on the Amazon forest. We find that total NPP remained constant throughout the drought. However, towards the end of the drought, autotrophic respiration, especially in roots and stems, declined significantly compared with measurements in 2009 made in the absence of drought, with extended decreases in autotrophic respiration in the three driest plots. In the year after the drought, total NPP remained constant but the allocation of carbon shifted towards canopy NPP and away from fine-root NPP. Both leaf-level and plot-level measurements indicate that severe drought suppresses photosynthesis. Scaling these measurements to the entire Amazon basin with rainfall data, we estimate that drought suppressed Amazon-wide photosynthesis in 2010 by 0.38 petagrams of carbon (0.23–0.53 petagrams of carbon). Overall, we find that during this drought, instead of reducing total NPP, trees prioritized growth by reducing autotrophic respiration that was unrelated to growth. This suggests that trees decrease investment in tissue maintenance and defence, in line with eco-evolutionary theories that trees are competitively disadvantaged in the absence of growth6. We propose that weakened maintenance and defence investment may, in turn, cause the increase in post-drought tree mortality observed at our plots.

Drought impact on forest carbon dynamics and fluxes in Amazonia