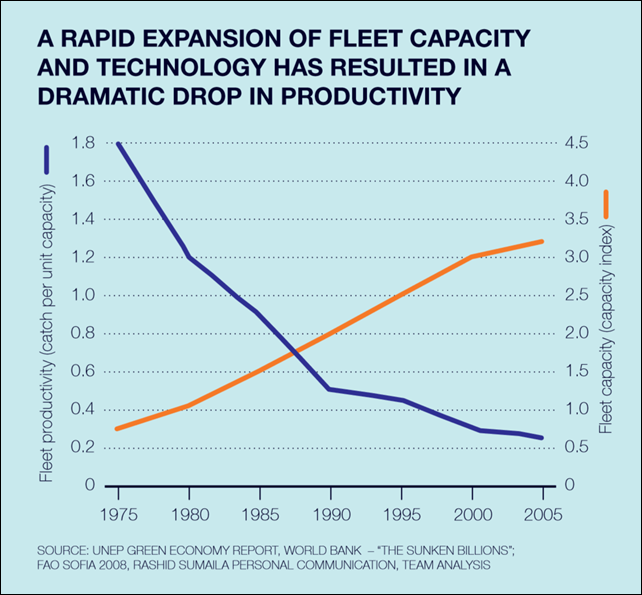

Graph of the Day: Global fishing fleet capacity and productivity, 1975-2005

24 June 2014 (Global Oceans Commission) – The main drivers leading to overfishing on the high seas are vessel overcapacity and mismanagement. However, measures to improve management alone will not succeed without solving the problem of overcapacity caused by subsidies, particularly fuel subsidies. Overcapacity is often described as “too many boats trying to catch too few fish”. Indeed, the size of the world’s fleet is currently two-and-a-half times what is necessary to sustainably catch global fish stocks. But it is not only the number of vessels that is of concern, it is also the type of vessel. Many argue that having fewer vessels, when they have larger engines and use more-destructive industrial fishing gear, is of equal weight to the number of vessels fishing as a driver of overcapacity. Many high seas fisheries destroy value from a societal perspective as the industry requires significant amounts of subsidies to achieve operating profits. This raises significant equity concerns since, in most cases, only those States that can afford subsidies have the opportunity to fish the high seas. Economic models show that the introduction of cost-reducing subsidies in a fishery system encourages the increase of fishing effort. Vessel overcapacity can be tied to government subsidies because the reduction of operating costs enables the activity to continue when it might not otherwise be economically viable. “Capacity-enhancing” subsidies include tax exemption programmes; foreign access agreements; boat construction renewal and modernising programmes; fishing port construction and renovation programmes; fishery development projects and supporting services; and fuel subsidies. As an example specific to the high seas, subsidies for the high seas bottom trawl fleets of the 12 top high seas bottom trawling nations amount to US$152 million per year, which represents 25% of the total landed value of the fleet. Typically, the profit achieved by this vessel group is not more than 10% of landed value, meaning that this industry effectively operates at a deficit.

From Decline to Recovery – A Rescue Package for the Global Ocean [pdf]

"The main drivers leading to overfishing on the high seas are vessel overcapacity and mismanagement."

No. The main drivers leading to overfishng….. is…. what for it….. OVERPOPULATION.

You know. That giant, undiscussed, politically incorrect and religiosly guarded "secret" that can't be discussed.

Virtually NOTHING on planet Earth will be resolved by refusing to address the core problem of "too many people demanding too much".

End of story.

If i remember correctly this graph is remarcably similar to the overcapacity vs landings of whale oil once the population levels had began to plummet due to overharvesting.

The only problem in this case is that instead of going after just one kind of species (whales) we are literally assaulting a whole segment of the marine ecosystem.

whereas some whale populations have rebounded, and might be in the mend (some, not all) The obliteration of a whole segment of an ecosystem will carry far deeper consequences, and very likely a much longer recovery process. A process that things like ocean acidification, eutropification, and the introduction of invasive species might delay, or even negate.

The biosphere as we know it is really coming to an abrumpt..change

MARR