A year into Detroit’s bankruptcy, many residents still feel abandoned – ‘It’s more than a tough pill to swallow. It’s tantamount to eating an elephant in one bite.’

By Alana Semuels

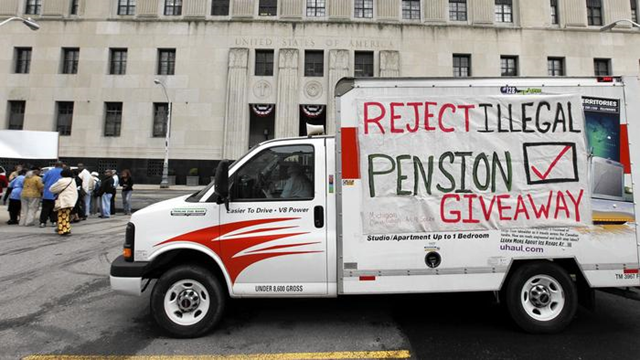

16 July 2014 DETROIT (Los Angeles Times) – In the year since this city filed for bankruptcy, becoming the largest municipality ever to do so, leaders have adopted a more optimistic tone about the future, pledging to fix streetlights and attract new residents and jobs.. But Eric Byrd isn’t buying it. “No change round here yet,” said the 30-year-old, looking around his neighborhood on the west side of the city. Nearly every house on the block is abandoned, hollowed out by fire or vandals. Yards have been reclaimed by tall grass and wildflowers, and the roads are potholed and empty. By all accounts, Detroit’s bankruptcy has been handled quickly and evenhandedly under the guidance of Judge Steven Rhodes. Already, the city has come up with a plan of adjustment and given retirees and employees the chance to vote on it; their ballots were due July 11. It also has enlisted $816 million from private funds and the state to help limit cuts to city pensions and protect the Detroit Institute of Arts from a fire sale. The city even recently launched an initiative to recruit natives back to the city, inviting them to an event to experience the new Detroit. Not everyone is impressed, though, especially current and past city employees, who have seen big changes to their health insurance and probably will see reductions in their pensions. Their anger was evident Tuesday, when Rhodes held a hearing to give some the opportunity to voice their objections to the bankruptcy. “It’s more than a tough pill to swallow. It’s tantamount to eating an elephant in one bite. And I can’t do that,” said Beverly Holman, a city retiree, in her testimony. Their complaints are fueled by fear and distrust: that the process through which retirees had to accept or reject the bankruptcy plan was rigged; that the city is shutting off water to residents unfairly; that retirees will be forced on the dole if the bankruptcy plan goes forward; that City Council members are getting a 5% raise while many retirees are struggling to pay the bills. Perhaps the biggest objection was to this: The city says the pension funds overpaid into some retirees’ accounts and wants that money back. One man testified Tuesday that the city wanted $89,000 from him. Like all retirees in this situation, he has the option of paying it back in a lump sum or having his pension reduced. In a room open to the public to watch the proceedings, a crowd of 50 or so retirees had gathered, many of them saying they feared they would lose their homes if the bankruptcy plan went forward. They applauded and whooped during the testimony of Holman and others. Applauding is about all they can do at this point because the votes are already in and the city has hinted that the retirees have approved the plan. “My life is at stake because I can’t afford the insurance,” said Gisele Caver, another retiree, through tears after telling Rhodes that the cuts to her health plan have made it impossible to pay for the medicine she needs. [more]

A year into Detroit’s bankruptcy, many residents still feel abandoned

I feel bad for the people of Detroit. The infighting and bickering will continue for many more months.

Will Detroit be able to satisfy all parties involved?

The promises that were made could never be kept. They have kicked the can down the road as far as they could, and now reality has become evident.

Detroit, because its poor management and dwindling tax base, just happens to be the first large government institution that has been forced to capitulate, and basically reneg on their promises.

Get used to it, because more of this is coming, to other cities, to other states, and eventually even the federal government.