Global warming: The changing face of the Arctic

By Nicole Mortillaro

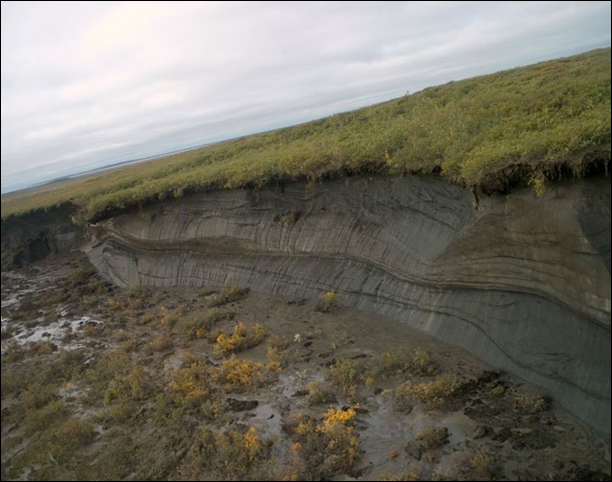

9 December 2013 TORONTO (Global News) – Autumns are now longer and warmer than they once were in the Arctic, and the first cases of sunburn were reported to researchers by Inuit in Tuktoyaktuk, according to a study on the effects of climate change on the Inuit culture. In the same study, Canadian Inuit Perspectives on Climate Change, Inuit reported skinnier and less healthy caribou, as a caribou food source — lichen — is becoming more difficult to get to due to winter freezing-rain events. The Inuit said it is more difficult to hunt as animals change their migration patterns. “Climate change is already having very detrimental impacts on the Arctic environment, including melting permafrost leading to the collapse of buildings and houses, ‘drunken’ forests, disappearing sea ice (and with it, loss of the environment that is home to the walrus and polar bear), and massive disturbance of ecosystems,” Michael Mann, distinguished Professor of Meteorology at Penn State University and author of the book The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars told Global News. is this variability and unpredictability that is making life in the Arctic more difficult. Three recent studies back up those claims: according to these studies (including one in November from journal PLoS One), permafrost is thawing, releasing methane into the atmosphere and changing the vegetation. Some of the biggest effects of climate change can be seen in the northern ecosystems. Take the Mackenzie Delta, for instance. The delta is home to large populations of fish, caribou, and other animals. But it is also rich in petroleum resources. In the 1970s and ’80s, petroleum companies sought to determine exactly how much oil and gas lay beneath the surface. In doing so, they drilled test sites around several areas of the Mackenzie Delta. Once testing was completed, the companies covered the massive pits, creating sumps. They believed that the permafrost would keep the saline water used in the drilling in a permanent state. However, with climate change, the permafrost is no longer so permanent. If the Arctic continues to warm as it has been, it will continue to thaw permafrost, creating melt ponds. In fact, in some areas, this is already happening. These thaw ponds can leach the saline solution into the ground and surrounding natural ponds. A recent study conducted by researchers at Queen’s University, Brock University, the University of Ottawa, Carleton University and the Northwest Geoscience Office examined the effects of these sump thaws. We had 101 lakes, 20 of them had sumps in them…what the petroleum industry left behind,” said John Smol, professor of biology Queen’s University and Canada Research Chair in Environmental Change. “And 34 … had obvious thaw slumps, which means permafrost falling apart. “Looking at the water chemistry, it was quite clear that many of the lakes that were in close proximity to the petroleum industry sumps, had higher salinity or higher chloride concentration,” said Smol. “And the question was … if they’re falling apart, what does that mean to the local ecology?” [more]