Greenland melting – ‘It’s hard to get your mind around how fast the Arctic is changing’

By Jeff Goodell

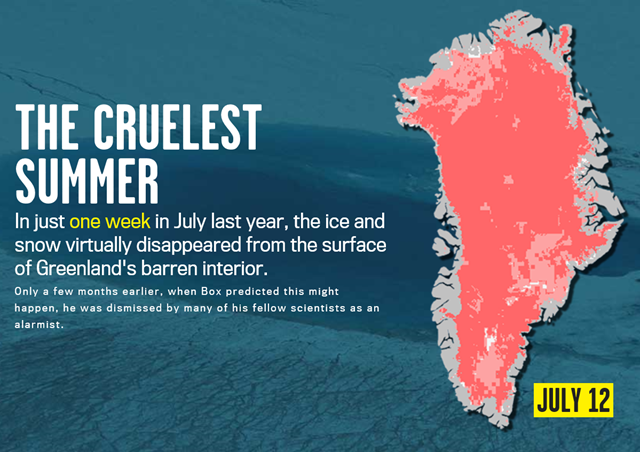

12 July 2013 (Rolling Stone) – A few weeks ago, on a blue-sky day on the west coast of Greenland, our helicopter swooped along the calving front of the Jakobshavn glacier, flying dangerously close to a 400-foot-high wall of ancient melting ice that stretches for about six miles across Disko Bay. Jakobshavn is the fastest-moving glacier in the world, and it is sliding into the sea at a top speed of 170 feet a day. How quickly this giant slab of ice and snow – and hundreds like it across the North and South Poles – disappears is the biggest uncertainty in the world of climate science. The faster these glaciers melt, the faster seas will rise, inundating cities throughout the world, and the more unpredictable the world’s weather system is likely to become. Our future is written in ice. The chopper cruised back and forth at the southern edge of the glacier, looking for a patch of open ground that Jason Box, a 40-year-old glaciologist who is leading the expedition, had identified in satellite photos. Box and the pilot exchanged words on the intercom, then Box gave a thumbs up. The chopper touched down on an unremarkable stretch of rocky tundra about the size of a Walmart parking lot, and Box jumped out, followed by a videographer. “Welcome to New Climate Land,” he announced and then launched into a giddy, erudite stand-up monologue for the camera that would have made his high school science teacher proud. “For thousands of years,” he explained, this spot had been covered by a tall building’s worth of ice and snow. But now, in the past few months, the final traces of that ancient ice had disappeared. “We are likely to be the first human beings to ever stand on this piece of ground,” Box said excitedly. It was all a tad melodramatic, perhaps. But Box doesn’t shy away from bold strokes. As he sees it, the general public has been betrayed by the reluctance of climate researchers to speak about the dangers of climate change with sufficient urgency. For Box, this has never been a problem. In 2009, he announced the Petermann glacier, one of the largest in Greenland, would break up that summer – a potent sign of how fast the Arctic was warming. Most glaciologists thought he was nuts – especially after the summer passed and nothing happened. In 2010, however, Petermann began to calve; two years later, it was shedding icebergs twice the size of Manhattan. Another example: In early 2012, Box predicted there would be surface melting across the entirety of Greenland within a decade. Again, many scientists dismissed this as alarmist claptrap. If anything, Box was too conservative – it happened a few months later. He also believes that the climate community is underestimating how much sea levels could rise in the coming decades. When I ask him if he thinks the high-end projections of six feet are too low, he doesn’t hesitate: “Shit, yeah.” “Jason has one very important quality as a scientist,” says Thomas Painter, a research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “He is willing to say crazy stuff and push the boundaries of conventional wisdom.” Though Box had predicted the severity of last summer’s melt, he struggled to understand why so much ice disappeared so quickly. Some climate modelers pointed to changes in atmospheric circulation patterns that pushed up temperatures across the Arctic. Others attributed it to the heat-trapping properties of low clouds. But Box decided to return to Greenland this summer – his 24th trip here in the past 20 years – to test a more startling hypothesis, part of what he calls “a unified theory” of glaciology: that tundra fires in Canada, massive wildfires in Colorado and pollution from coal-fired power plants in Europe and China had sent an unexpectedly thick layer of soot over the Arctic region last summer, which settled onto Greenland’s vast frozen interior, increasing the amount of sunlight the snow and ice absorbed, which in turn accelerated the melting. It was a powerful connection – but was it true? Savvy packager that he is, Box hasn’t just put forth this theory in scientific journals and grant proposals. He’s also branded it: The expedition, called the Dark Snow Project, is the first crowd-sourced scientific research trip to Greenland. “The old ways of doing things aren’t working,” Box tells me one evening. “I want to pursue big ideas, but I also want to communicate them in ways that the public understands. Scientists need to do everything they can to wake people up. It is our job, our moral responsibility.” “It’s hard to get your mind around how fast the Arctic is changing,” said Jennifer Francis, an atmospheric scientist at Rutgers University. According to NASA, Greenland and Antarctica are losing three times as much ice each year as they did in the 1990s. Summer sea-ice cover is half as big as it was from 1979 to 2000, and many scientists are predicting an ice-free Arctic by the end of the decade. Not so long ago, the Northwest Passage, the storied northern route from the Atlantic to the Pacific oceans, required an icebreaker ship to navigate it. This summer, people are attempting the passage in a sea kayak. [more]