Investors embrace climate change, chase hotter profits – ‘The climate is changing. Sea level is rising. That’s quite obvious. Cities close to the waterline continue to grow and need more protection. It’s almost a natural growth market.’

By Matthew Campbell and Chris V. Nicholson

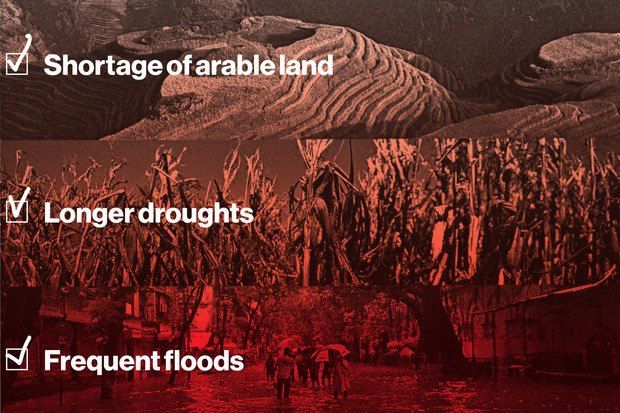

7 March 2013 (Bloomberg) – Investing in climate change used to mean financing the fight against global warming. Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs Group Inc., and other firms took stakes in wind farms and tidal-energy projects, and set up carbon-trading desks. Then, as efforts to curb greenhouse-gas emissions faltered, the appeal of clean tech dimmed: Venture capital and private- equity investments fell 34 percent last year, to $5.8 billion, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Now the smart money is taking another approach: Working under the assumption that climate change is inevitable, Wall Street firms are investing in businesses that will profit as the planet gets hotter. The World Bank said in November that the planet is on track to warm by 4 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, and risks “cataclysmic changes” as a result. Rising seas threaten floods in cities from Mexico to Mozambique; heat waves menace crop yields in India, the U.S. and Australia; and warming oceans may destroy coral reefs, it said. Betting on the failure of global efforts to contain warming may seem cynical, but it’s increasingly logical. Fifteen years after the Kyoto Protocol to rein in greenhouse gas emissions in industrialized countries was reached, the world is still without a comprehensive pact binding all emitters to deal with the issue. Since 1990, the benchmark for Kyoto’s emissions targets, global carbon dioxide output from fossil fuels has increased by 49 percent to 31.2 gigatons, according to International Energy Agency data. About 70 percent of the new emissions through 2010 came from China, the U.S. and India, the three biggest polluters. None are bound by Kyoto, a treaty the U.S. never ratified because it didn’t set targets for developing nations. Investor strategies include buying water-treatment companies, brokering deals for Australian farmland, and backing a startup that has engineered a mosquito to fight dengue, a disease that’s spreading as the mercury climbs. Derivatives that help companies hedge against abnormal weather and natural catastrophes are also drawing increased interest from some big players. In January, KKR & Co. bought a 25 percent stake in Nephila Capital Ltd., an $8 billion Bermuda hedge fund that trades in weather derivatives. The firm is named after a spider that, according to local folklore, can predict hurricanes. “Climate risk is something people are paying more and more attention to,” said Barney Schauble, managing partner at Nephila Advisors, the firm’s U.S. arm. “More volatile weather creates more risk and more appetite to protect against that risk.” One form of extreme weather — drought — is helping spur business at Water Asset Management LLC. The New York hedge fund, which has about $400 million under management, buys water rights and makes private equity and stock-market investments in water- treatment companies.

“Not enough people are thinking long term of (water) as an asset that is worthy of ownership,” said Water Asset Management Chief Operating Officer Marc Robert. “Climate change for us is a driver.” When investors think about global warming, “there is an overemphasis of its negative impacts,” said Michael Richardson, head of business development at Land Commodities, which advises rich individuals and sovereign wealth funds on purchases of Australian farmland. The company’s pitch: The prospect of hotter temperatures, scarce arable land, and rising populations will make inland cropland Down Under — far from rising seas yet close to Asia’s hungry customers — more valuable. The Baar, Switzerland-based company worked on more than $80 million in transactions last year, four times its 2011 total, Richardson said. For Ole Christiansen, the climate isn’t changing fast enough. Indeed, the chief executive officer of NunaMinerals A/S (NUNA), a mining startup based in Nuuk, Greenland, is counting on it. The 1,500-mile long ice sheet that covers the Danish territory is melting, exposing what Christiansen and other mining and energy executives say could be a bonanza of gold, rare earths, and base metal deposits that will attract deals and capital to one of the most remote corners of the world. For Nuna, simply put, less ice means more money. “Last summer, we were exploring in south Greenland, mainly for gold,” Christiansen said. “It has previously been covered by a glacier, but most of that glacier has disappeared, so suddenly we had access to a lot of ground that nobody had seen before.” […] In 2011, the management consultancy Mercer laid out various scenarios for asset values depending on how much temperatures rise. Among the “positive impacts” for warming up to 3 degrees: higher crop productivity in temperate latitudes, and a “decreased requirement for space heating.” On the negative side of the ledger: “malnutrition, heat stress, extreme events,” and “increasing adaptation costs in all regions to protect against flood risk.” Those downsides may hold significant opportunities, with the UN estimating the additional investment needed to adapt new infrastructure to climate change will total as much as an annual $130 billion by 2030. “The population is growing and more people want to live on the coastlines, so we keep building more valuable properties in harm’s way,” said Karen Clark, an expert in catastrophe risk who advises financial institutions. “We need to be rebuilding more resilient communities.” A leader in this field is Arcadis NV (ARCAD), a Dutch engineering firm that offers flood-protection services. The company has been on a buying spree in recent years, most recently snapping up ETEP Consultoria, Gerenciamento, e Servicos Ltda., a Brazilian water engineering and consulting firm. Arcadis’s revenue was up 26 percent last year, to 2.5 billion euros ($3.2 billion), thanks in part to superstorm Sandy. The company won contracts from New York’s Nassau County and New York City to help bring water-treatment facilities back online. In the past it has worked with authorities in New Orleans to upgrade levees and in San Francisco to create a plan to deal with rising sea levels. Piet Dircke, who oversees water management at Arcadis, said his phone was ringing nonstop in the days after Sandy. “The climate is changing. Sea level is rising. That’s quite obvious,” said Dircke. “At the same time, the cities that are close to the waterline continue to grow and have more money and need for protection. It’s almost a natural growth market.” [more]

Fucking capitalists.

They'd sell their own mothers to Satan if they could turn a profit.