Greenland ice sheet melt nears critical tipping point ‘into a state of inevitable decline’

By Andrew Freedman

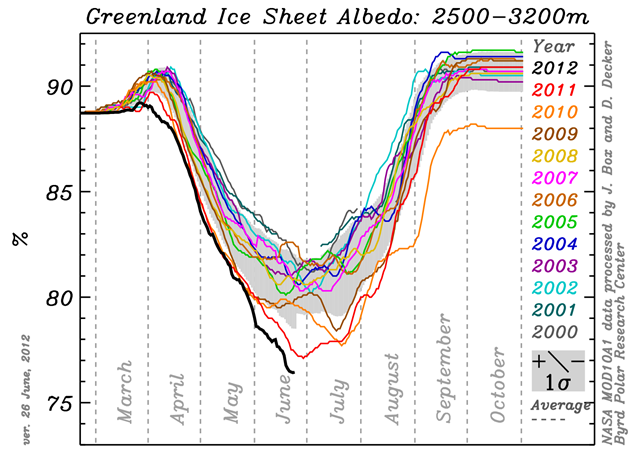

29 June 2012 The Greenland ice sheet is poised for another record melt this year, and is approaching a “tipping point” into a new and more dangerous melt regime in which the summer melt area covers the entire land mass, according to new findings from polar researchers. The ice sheet is the focus of scientific research because its fate has huge implications for global sea levels, which are already rising as ice sheets melt and the ocean warms, exposing coastal locations to greater damage from storm surge-related flooding. Greenland’s ice has been melting faster than many scientists expected just a decade ago, spurred by warming sea and land temperatures, changing weather patterns, and other factors. Until now, though, most of the focus has been on ice sheet dynamics — how quickly Greenland’s glaciers are flowing into the sea. But the new research raises a different basis for concern. The new findings show that the reflectivity of the Greenland ice sheet, particularly the high-elevation areas where snow typically accumulates year-round, have reached a record low since records began in 2000. This indicates that the ice sheet is absorbing more energy than normal, potentially leading to another record melt year — just two years after the 2010 record melt season. “In this condition, the ice sheet will continue to absorb more solar energy in a self-reinforcing feedback loop that amplifies the effect of warming,” wrote Ohio State polar researcher Jason Box on the meltfactor.org blog. Greenland is the world’s largest island, and it holds 680,000 cubic miles of ice. If all of this ice were to melt — which, luckily won’t happen anytime soon — the oceans would rise by more than 20 feet. In a new study, Box and a team of researchers describe the decline in ice sheet reflectivity and the reasons behind it, noting that if current trends continue, the area of ice that melts during the summer season is likely to expand to cover all of Greenland for the first time in the observational record, rather than just the lower elevations at the edges of the continent, as is the case today. The study has been accept for publication in the open access journal The Cryosphere. The high reflectivity of snow is what has kept Greenland so cold by redirecting incoming heat from the sun back out toward space. But with several factors combining to increase temperatures in Greenland and reduce the reflectivity of the snow and ice cover, the ice sheet is becoming less efficient at reflecting that heat energy, and as a consequence melt seasons are becoming more severe. Freshly fallen snow reflects up to 84 percent of incoming sunlight, but during the warm season the reflectivity declines as the ice grains within the snowpack change shape and size. In addition, once snow cover melts completely it often reveals underlying ice that has been darkened by dust and other particles, whose surface absorbs more solar energy, promoting heating. Box’s research has shown that the change in the reflectivity of the Greenland ice sheet during the 12 summers between 2000 and 2011 allowed the ice sheet to absorb an extra 172 “quintillion joules” of energy, nearly twice the amount of energy consumed in the U.S. in 2009. This extra energy has gone into raising the temperature of the snow and ice cover during summer. “If the area of the Greenland Ice Sheet experiencing net melt expands to eclipse the accumulation zone of the ice sheet, the ice sheet will, by definition, be tipped into a state of inevitable decline,” said William Colgan, a research associate at the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) who did not participate in the new research. […]

Greenland Ice Sheet Melt Nearing Critical ‘Tipping Point’