‘Past the tipping point’ – Megafires may change the U.S. Southwest forever

By Brandon Keim

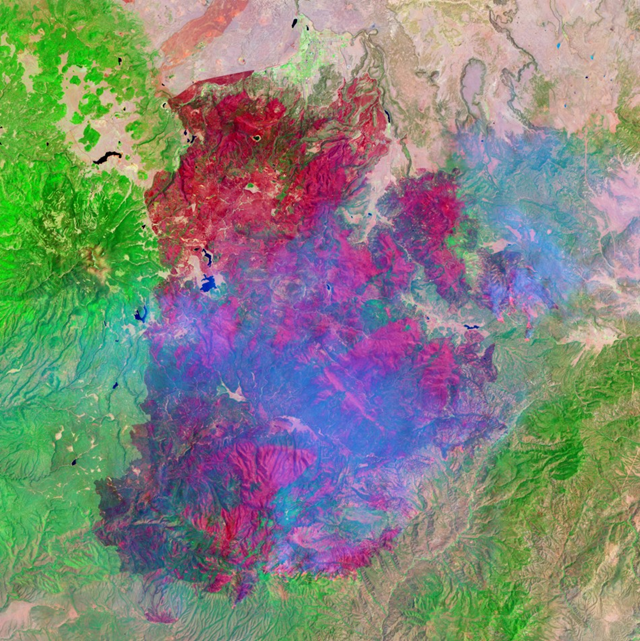

June 30, 2011 The plants and animals of the southwestern United States are adapted to fire, but not to the sort of super-sized, super-intense fires now raging in Arizona. The product of drought and human mismanagement, these so-called megafires may change the southwest’s ecology. Mountainside Ponderosa forests could be erased, possibly forever. Fire may become the latest way in which people are profoundly altering modern landscapes. “If a few acres burn, a forest can recover. But at really large scales, the opportunity to recover is limited,” said forest ecologist Dan Binkley of Colorado State University. “The large-scale devastation has taken away the ecological future.” Fire itself is not rare in the southwest. It’s a constant feature, not at all distressing, a fact obscured by the tendency of local news stations to seize upon dramatic footage of every flame-encroached house. But fires like the ongoing Wallow fire, already the largest in Arizona’s recorded history, and the record fires seen in Texas in April, are fairly unusual. They used to happen every few centuries, but now seem to happen every few years. That’s partly because of a severe ongoing drought, but also because people have spent the last century trying to protect settled areas by putting out every small fire. That allows shrubs to grow, needles and twigs to gather on the ground, and low-hanging branches to spread. The southwestern region known as the Sky Islands, where tree-covered mountain ranges rise from desert valleys, has become a series of tinderboxes. […] To show how fire traditionally behaved, fire ecologist Don Falk of the University of Arizona pointed to the Miller fire, a blaze that started in May in the Gila National Forest. Because the region is so sparsely settled, forest managers have historically allowed burns to run their course. The latest fire covered 90,000 acres, but it wasn’t intense. Animals could escape and completely defoliated areas were small. […] “The sorts of plants that thrive during droughts are different than those that survive in normal times,” said Falk. For at least the next few centuries, if not millenniums, towering Ponderosa forests will not come back. Instead there will be pine and Gambel oak and New Mexico locust trees. “It will convert to a more shrubby ecosystem. The system will have gone past the tipping point.” […]