Earth’s greatest mass extinction caused by coal: study

About 250 million years about 95 per cent of life was wiped out in the sea and 70 per cent on land. Researchers at the University of Calgary believe they have discovered evidence to support massive volcanic eruptions burnt significant volumes of coal, producing ash clouds that had broad impact on global oceans. About 250 million years ago, about 95 percent of life was wiped out in the sea and 70 percent on land. Researchers at the University of Calgary believe they have discovered evidence to support massive volcanic eruptions burnt significant volumes of coal, producing ash clouds that had broad impact on global oceans. “This could literally be the smoking gun that explains the latest Permian extinction,” says Dr. Steve Grasby, adjunct professor in the U of C’s geoscience department and research scientist at Natural Resources Canada. Grasby and colleagues discovered layers of coal ash in rocks from the extinction boundary in Canada’s High Arctic that give the first direct proof to support this and have published their findings in Nature Geoscience.

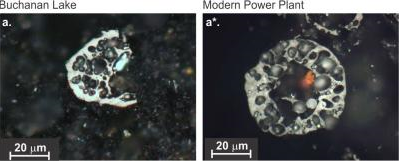

Unlike the end of the dinosaurs, 65 million years ago—where there is widespread belief that the impact of a meteorite was at least the partial cause—it is unclear what caused the late Permian extinction. Previous researchers have suggested massive volcanic eruptions through coal beds in Siberia would generate significant greenhouse gases causing run away global warming. “Our research is the first to show direct evidence that massive volcanic eruptions—the largest the world has ever witnessed—caused massive coal combustion thus supporting models for significant generation of greenhouse gases at this time,” says Grasby. At the time of the extinction, the Earth contained one big land mass, a supercontinent known as Pangaea. The environment ranged from desert to lush forest. Four-limbed vertebrates were becoming more diverse and among them were primitive amphibians, early reptiles and synapsids: the group that would, one day, include mammals. The location of volcanoes, known as the Siberian Traps, are now found in northern Russia, centered around the Siberian city Tura and also encompass Yakutsk, Noril’sk and Irkutsk. They cover an area just under two-million-square kilometers, a size greater than that of Europe. The ash plumes from the volcanoes travelled to regions now in Canada’s arctic where coal-ash layers where found. Grasby studied the formations with Dr. Benoit Beauchamp, a fellow professor in the geosciences department. They called upon Dr. Hamed Sanei adjunct professor at the U of C and a researcher at NRCan to look at some of peculiar organic layers they had discovered. “We saw layers with abundant organic matter and Hamed immediately determined that they were layers of coal-ash, exactly like that produced by modern coal burning power plants,” says Beauchamp. Sanei adds: “Our discovery provides the first direct confirmation for coal ash during this extinction as it may not have been recognized before.” The ash, the authors suggest, may have caused even more trouble for a planet that was already heating up with its oceans starting to suffocate because of decreasing oxygen levels. “It was a really bad time on Earth. In addition to these volcanoes causing fires through coal, the ash it spewed was highly toxic and was released in the land and water, potentially contributing to the worst extinction event in earth history,” says Grasby. Read the Nature Geoscience article, “Catastrophic dispersion of coal fly ash into oceans during the latest Permian extinction”.

Researchers find smoking gun of world’s biggest extinction

Desdemona accidentally deleted this comment from rpauli:

Wow ! Our civilization was SO close.

Here we recently learned that of our two neighboring planets – one is too hot and one is too cold.

Now we learn that too much coal burned up our world.

What else is it too late to learn?