By Stephen Leonard

By Stephen Leonard

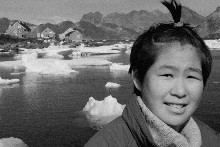

12:36 PM Saturday Oct 9, 2010 Melting sea ice threatens the way of life of Greenland’s Inughuit people, who hunt whale and seal by kayak and dog sled. Living in the most northern permanently inhabited settlements in the world, the Inughuit people, or Polar Eskimos as they are often known, have eked out an existence in this Arctic desert in the northwest corner of Greenland for centuries. The Inughuit are one of the smallest indigenous groups in the world with a population of just 800 people spread across the four settlements that make up the Thule region. Eighteen hundred kilometers away from the capital, Nuuk, and occupying an unfeasibly remote corner of our world, the Inughuit enjoy their own distinct subculture based on the hunting of marine mammals. Unlike other Inuit populations across the Arctic, the Inughuit have maintained where possible their ancient way of life, using kayaks and harpoons to hunt narwhal and travelling by dog-sled in the winter. This unique way of life is now under threat. A tiny society whose basis is just a half dozen families, some of whom are descendants of the polar explorers Robert Peary and Matthew Henson, say they are being “squeezed” out of existence. … My journey to Greenland took me through pretty, picture-postcard Ilulissat in the south. Small amphitheatres of ice collect dirt before sinking into oblivion. Skirting the ice sheet, heading northwards, it seemed grey and thinning. Lakes appeared all over the ice, a tragic testament of the all too rapidly changing natural environment. It is a picture of transition and a disturbing one at that: it speaks dislocation and a sense of foreboding. … But now these displaced people face a new and unprecedented threat to their culture: global warming. A local woman who has spent nearly all her life living in Qaanaaq stands in my green prefabricated wooden hut, on the vast polar bear and musk-oxen skins that cover the floor. Dried, pungent blubber sits on the racks outside. Looking out across Ingelfield Bay and the whale-shaped Herbert Island, towards the exploding icebergs that sit like vast lumps of polystyrene in the Murchison Sound, there is a sadness in her eyes: “Twenty years ago, my children used to go skating on the ice at this time of the year. Just 15 years ago, the sea ice in the bay was up to 3m thick. Last year the ice was so thin that a young hunter and his dog team of 12 fell through the thin ice to their early deaths. If the sea ice goes completely, there will be no need for the dogs [huskies] and our culture will disappear.” …

Vanishing world of the last Arctic hunters via The Oil Drum

Technorati Tags:

Greenland,

global warming,

climate change,

climate refugees,

deglaciation,

glacier,

ice sheet,

sea ice,

mammal decline,

marine mammal,

Arctic

By Stephen Leonard