Graph of the Day: Arctic Sea Ice Change, 1981-2010

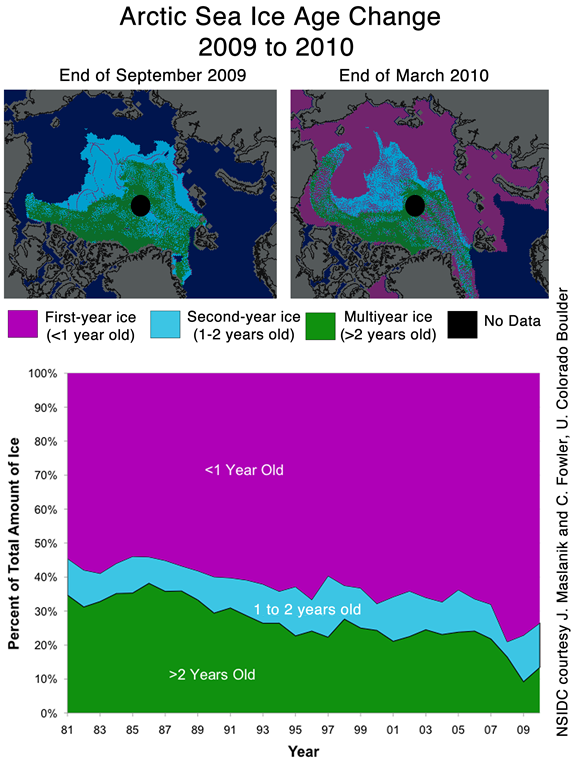

These images show the change in ice age from fall 2009 to spring 2010. The negative Arctic Oscillation this winter slowed the export of older ice out of the Arctic. As a result, the percentage of ice older than two years was greater at the end of March 2010 than over the past few years. The late date of the maximum extent, though of special interest this year, is unlikely to have an impact on summer ice extent. The ice that formed late in the season is thin, and will melt quickly when temperatures rise. Scientists often use ice age data as a way to infer ice thickness—one of the most important factors influencing end-of-summer ice extent. Although the Arctic has much less thick, multiyear ice than it did during the 1980s and 1990s, this winter has seen some replenishment: the Arctic lost less ice the past two summers compared to 2007, and the strong negative Arctic Oscillation this winter prevented as much ice from moving out of the Arctic. The larger amount of multiyear ice could help more ice to survive the summer melt season. However, this replenishment consists primarily of younger, two- to three-year-old multiyear ice; the oldest, and thickest multiyear ice has continued to decline. Although thickness plays an important role in ice melt, summer ice conditions will also depend strongly on weather patterns through the melt season. At the moment there are no Arctic-wide satellite measurements of ice thickness, because of the end of the NASA Ice, Cloud, and Land Elevation Satellite (ICESat) mission last October. NASA has mounted an airborne sensor campaign called IceBridge to fill this observational gap.