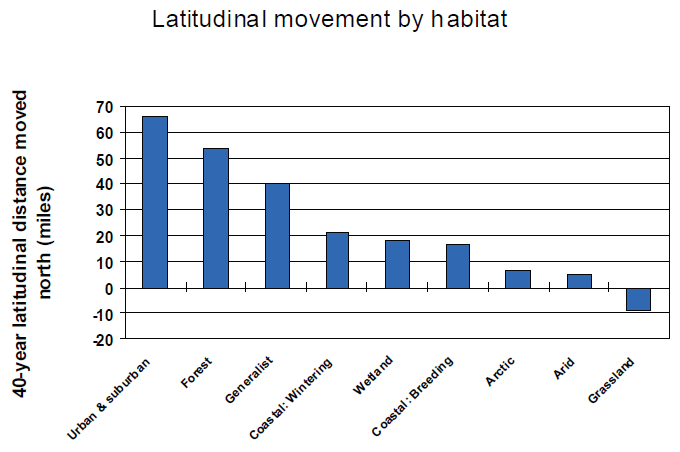

Graph of the Day: Latitudinal movement of US bird species by habitat, 1960s-2006

Christmas Bird Count (CBC) show that the warmer winters in recent decades have played an important role in shifting winter bird ranges to the north. CBC data from the mid-1960s through 2006 show that 170 (56%) of the 305 most widespread, regularly occurring species have shifted their ranges to the north, whereas only 71 species (23%) have shifted to the south and 64 species (21%) have not shifted significantly north or south. Species also shifted east or west, but an equal number of species moved east as moved west. Overall, the average shift over 40 years was 35 miles north. Many of the species that increased in northern states or provinces also decreased in southern states. Among states and provinces, rates of bird population change are correlated with rates of temperature change, independent of latitude.

During the 40 years of the study, birds were found farther north in winters that were relatively warm and father south in colder winters. Predictions of future temperature changes suggest that birds will continue to shift north and that more sedentary species may be vulnerable if they are unable to shift as temperatures increase. Birds in most habitats showed the northern range shift (see graph). Urban and suburban birds shifted the most, and forest birds shifted the second most. Arctic and aridland birds did not show biologically important shifts, and grassland birds were the only group that shifted to the south more than to the north. Generalists (species with fewer specific habitat preferences) shifted their ranges north more than those with more specific habitat preferences except for forest birds. Each of the 305 species in the study showed a different amount of range shift. Some birds and many other species of wildlife are not able to shift rapidly in response to changing temperatures. If climate continues to change, future wildlife communities will look very different from those of today.