Research shows continued decline of Oregon’s largest glacier

Media Contact: David Stauth, 541-737-0787

Source: Cody Beedlow, 541-737-1248

3 September 2010

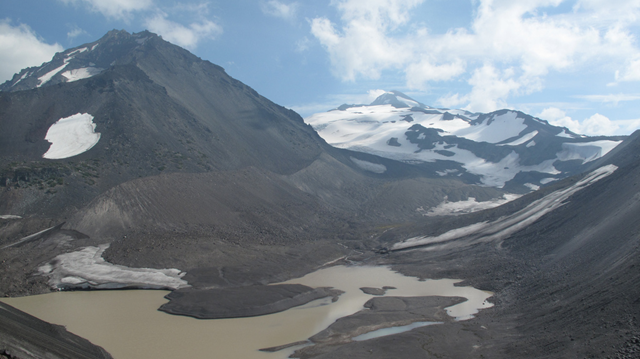

CORVALLIS, Ore. – An Oregon State University research program has returned to Collier Glacier for the first time in almost 20 years and found that the glacier has decreased more than 20 percent from its size in the late 1980s. The findings are consistent with glacial retreat all over the world and provide some of the critical data needed to help quantify the effects of global change on glacier retreat and associated sea level rise. Flowing down the flanks of the Three Sisters in the central Oregon Cascade Range, Collier Glacier is at an elevation of more than 7,000 feet. It’s one of the largest glaciers in Oregon and is on a surprisingly short list – maybe 100 in the entire world – of glaciers that have been intensively studied and monitored for extended periods of time. Glacier monitoring is difficult, dangerous and labor-intensive, OSU researchers say, and the current work, supported by the National Science Foundation, is showing an ice mass that by now has shrunk to about half of its peak size in the 1850s, when it once was nearly two miles long. Monitoring has been aided by records from early Oregon mountaineering clubs, particularly the Mazamas, founded in 1894 on the summit of Mount Hood. A research program that began last year and is continuing this summer is now finding some rocks that are being exposed to daylight for the first time in thousands of years. “Glaciers can tell us a lot about climate change, because they respond to both changes in temperature and precipitation,” said Peter Clark, an OSU professor of geosciences who conducted the last studies on Collier Glacier in the late 1980s and early 1990s. “They are like a checking account where you make both deposits and withdrawals, and can see the long-term effects of climate change, through the year-to-year variation in the balance between the two.” … In most of the world, including the Pacific Northwest, glaciers have been in a slow global retreat since the end, in the late-1800s, of a 600-year period called the “Little Ice Age,” Clark said. Some of that melting will cause a noticeable increase in sea level, and some water resources will be affected where glacial fields feed irrigation streams and reservoirs. … Some of the locations where researchers now camp would have been several hundred feet deep in ice in the 1800s.

Research Shows Continued Decline of Oregon’s Largest Glacier