In Colorado, freedom to burn – ‘It ain’t our fire’

By DINA FINE MARON of ClimateWire

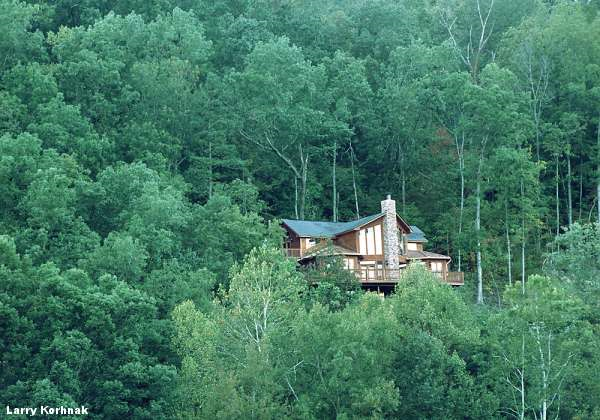

October 26, 2010 FOURMILE CANYON, Colo. — On a hot afternoon in late September, Allen Owen looked into the distance, hoping for rain. He crawled along unmarked dirt roads in his white Dodge Ram four-wheel drive truck, passing handwritten signs saying, “Thank you firefighters!” and “Be hopeful!” surveying the mounds of charred metal and debris that had been homes just three weeks earlier. There was other damage he couldn’t see. The state’s emergency wildfire fund was now down to zero — drained to extinguish the blazes that cut through more than 6,000 acres of land that month. As for the local and federal firefighting forces that brought the fire under control after eight days, they were exhausted. Though the fire had been contained, Owen, the Boulder District forester for the Colorado State Forest Service, was still worried. Fire had dried out the trees and brush that had not succumbed to the blazes, and the resulting risk of future fire on the Front Range was high. Weeks earlier, fierce winds had apparently helped embers from a backyard fire pit take flight, and the resulting megafire had destroyed more than 160 homes in an area where fancy suburban houses are nestled in woodland settings several miles west of Boulder. Land managers call places like this “the wildland-urban interface,” or WUI, for short. As Western forests grow hotter and drier, WUI areas have become an increasingly risky and expensive proposition for nearly everyone involved. This most recent fire cost roughly $10 million to fight and caused an estimated $217 million in property damage, making it the most expensive wildfire in Colorado history. Fires like this put questions about climate change into stark relief: With climate models predicting snowpack melts earlier, giving way to future hotter, drier summers, there will likely be increased fire risk. Meanwhile, homes that are continuing to sprout up within wildlands are not helping the situation. Roughly 20 percent of Coloradans — 1 million people — have chosen to live close to nature, surrounded by that wilderness high-risk space. But the same trees that give homeowners their seclusion also could incinerate their property. … But in Colorado, at least, the people who chose to live in homes abutting wilderness are not planning on surrendering the territory. In fact, the state’s population is projected to blossom in the next 30 years — with much of the growth expected to occur in those woodsy areas, according to the Colorado Statewide Forest Resource Assessment. …

In Colorado, Freedom to Burn — ‘It Ain’t Our Fire’

Nice to see those two stories grouped together. Somehow related.