Desdemona at 2: The Environmentalist’s Paradox

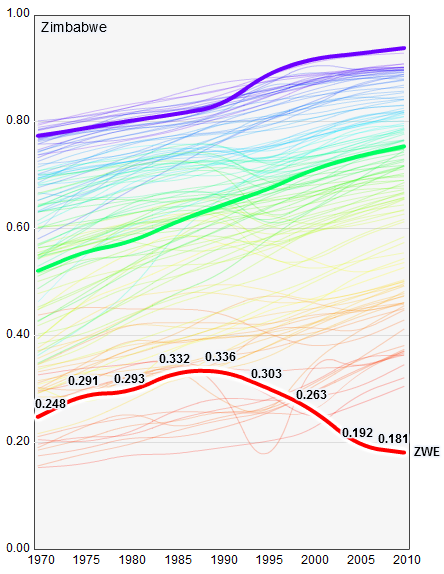

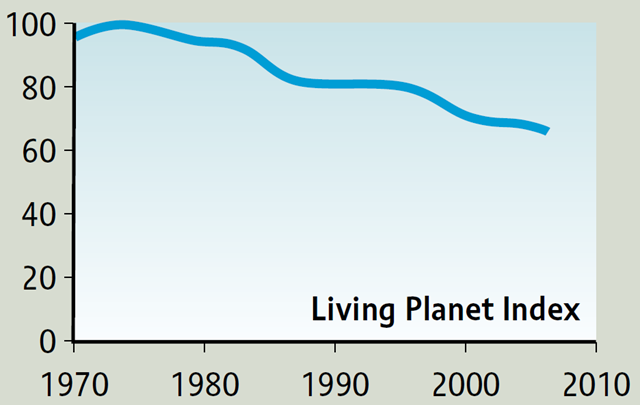

Of the many important results published during Desdemona’s second year of blogging, one stood out: a BioScience paper titled “Untangling the Environmentalist’s Paradox: Why Is Human Well-being Increasing as Ecosystem Services Degrade?” This question is central to the Desdemona Thesis. Essentially, the authors of this paper (Ciara Raudsepp-Hearne, et al.) challenge us to reconcile the following two graphs. The first shows the the Human Development Index (HDI), which is an aggregate measure of human well-being globally, for the 40-year period from 1970 to 2010. The second shows the Living Planet Index (LPI) for the same period. Despite a nearly 30 percent decline in the LPI, the HDI has risen for almost all nations.

| Worldwide Trends in the Human Development Index, 1970-2010. HDI values for all nations are shown. Zimbabwe (red) has the lowest score. Australia (violet) has the highest score, Turkey (green) the median score. hdr.undp.org |

| Global Living Planet Index, 1970-2007. The global index shows that vertebrate species populations declined by almost 30 per cent between 1970 and 2007. ZSL / WWF, 2010 / wwf.panda.org |

It’s an article of faith among doomers that as humans wreck the biosphere, the consequences for civilization will be severe. These graphs provide pretty solid empirical evidence that this hasn’t been the case over the 40-year time period studied here. The BioScience paper provides a framework for considering this paradox. From the abstract:

Environmentalists have argued that ecological degradation will lead to declines in the well-being of people dependent on ecosystem services. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment paradoxically found that human well-being has increased despite large global declines in most ecosystem services. We assess four explanations of these divergent trends: (1) We have measured well-being incorrectly; (2) well-being is dependent on food services, which are increasing, and not on other services that are declining; (3) technology has decoupled well-being from nature; (4) time lags may lead to future declines in well-being.

The authors acknowledge that there are other possible hypotheses:

We synthesized these four to represent major lines of discussion on the topic of ecosystem services and human wellbeing. Although we present the alternative explanations as individual hypotheses, they are not mutually exclusive.

The four hypotheses cover most of the reasonable scenarios that Desdemona could think of. The following table summarizes the authors’ conclusions. After that, Desdemona has a few thoughts.

| Hypothesis | Origin of hypothesis | Evaluation | Supporting Evidence |

| 1. Critical dimensions of declining human well-being are not captured adequately. | Debate on how to measure human well-being (Alkire 2002). | Rejected | Empirical, strong |

| 2. Only provisioning services are important for human well-being. Human well-being is not measurably affected by declines in regulating and cultural ecosystem services. | The Green Revolution demonstrated that human well-being dramatically increases with access to more food, which is far more important to well-being than other ecosystem services (e.g., Evenson and Gollin 2003). | Supported |

|

| 3.Technology and innovation have decoupled human well-being from ecosystem condition. | Environmental problems stimulate technological innovations that allow environmental problems to be overcome (e.g., Boserup 1976) |

|

Empirical, strong against decoupling of society and ecosystems, and for long-term increases in efficiency. |

| 4. There is a time lag after ecosystem service degradation before human well-being is affected. | Limits to Growth highlighted the idea that a society could develop to such an extent that it degrades the resources that sustain it (Meadows et al., 1972). | Mixed evidence |

|

And here’s the conclusion:

The environmentalist’s paradox is not fully explained by any of the four hypotheses we examined. Our evidence indicates that we can largely reject the hypothesis that human wellbeing is decreasing; however, some aspects of each of the other three hypotheses are supported, whereas other aspects are invalidated (table 3). For hypothesis 2, it is clear that agriculture provides benefits to humanity, but locally those benefits can be outweighed by the loss of other services. The efficiency with which people have been able to extract benefits from nature has increased, supporting hypothesis 3, but technological innovation has not decoupled society from the biosphere. And while there are many important time lags in Earth’s systems, which supports hypothesis 4, the consequences of those lags for human well-being are unclear.

Despite the conclusion that Hypothesis 4 has “weak empirical support,” Desdemona favors it over the others. The following sections describe the evidence for the four hypotheses in more detail. Critical dimensions of declining human well-being are not captured adequately Does the HDI really measure human well-being? The authors consider the obvious objections and present a strong refutation.

The indicators that are components of the composite HDI, specifically, GDP per capita, childhood survival, and education, are all improving at the global scale (WRl 2009). Although the HDI captures only some dimensions of human well-being, it is strongly correlated with other dimensions. A review by McGillivray (2005) found that health-adjusted life expectancy, adult and youth literacy, gender equality, and other measures are strongly correlated with the HDI. The most widely used data set for comparisons across nations of more abstract well-being indicators (such as happiness) is the World Values Survey (WVS; EWVS 2006), which shows a positive relationship between happiness and the HDI (Leigh and Wolfers 2006). Additionally, studies of social capital, or the value placed on social ties and networks, show a strong correlation with the subjective perceptions of happiness from the WVS (Bjornskov 2003), and thus with the HDI. Some measures of human well-being show more ambiguous trends. Personal security is one dimension of human well being that does not show clear trends, and by some measures is worsening at the global scale. For example, the total number of people displaced by warfare has increased since the 1940s (Mack 2005). Crime, as measured at the global level, including rates of homicide and rape, has more than doubled since the 1970s; however, because these data track reports of incidents rather than the underlying crimes themselves, they may not

accurately reflect actual crime (Mack 2005).

Desdemona finds nothing to dispute here, but the next objection does loom large.  Data aggregation masks declines in human well-being The potential problem here is with the weighting of the various inputs to the HDI. For example, there might be a bias that favors the Northern Hemisphere over the Southern Hemisphere, or smoothing that masks important regional effects. But the authors conclude that this can’t be the case, because several different metrics show that poverty is declining globally.

Data aggregation masks declines in human well-being The potential problem here is with the weighting of the various inputs to the HDI. For example, there might be a bias that favors the Northern Hemisphere over the Southern Hemisphere, or smoothing that masks important regional effects. But the authors conclude that this can’t be the case, because several different metrics show that poverty is declining globally.

Measuring average well-being across entire populations may cause us to overlook negative trends among segments of populations, or the effects of increasing global inequality. Nonetheless, the absolute number of people living in poverty—across a range of definitions—has consistently declined at the global scale over the past half century, with the percentage of people living in poverty dropping even faster.

If the HDI trend did not match the poverty trend, there would be cause for questioning one metric or the other. As it stands, the various metrics are mutually reinforcing. The authors conclude:

Despite weak evidence of declines in some aspects of well-being, existing global data sets strongly support the … finding that human well-being is increasing. … [T]he body of evidence does not support the hypothesis that a more comprehensive assessment of human well-being would resolve the environmentalist’s paradox by revealing declines in human well-being.

After two years of doom blogging, it’s hard for Desdemona to swallow this pill; with so much disaster pummeling humans from every direction, it’s counterintuitive to see these measurements trending upward, in spite of it all. But by every measure, the trend is real. Food production is more crucial than other ecosystem services for human well-being Maybe agriculture is more important than any other ecosystem service.

This hypothesis proposes that the benefits associated with greater provisioning services, in particular, food production, outweigh the costs of declines in other services.

In the engineer’s spirit of testing a model at its boundary conditions, this hypothesis invites us to imagine a world in which all ecosystem services have been destroyed, except for those that directly support agriculture. One can imagine a Soylent Green scenario, in which humans are the only remaining animal species, and they farm the anoxic, algae-dominated oceans for food. Would the HDI increase in such a world? Quite possibly, but it’s hard to argue that the experience would be an improvement for most of humanity.  The authors argue for thresholds and regional effects:

The authors argue for thresholds and regional effects:

In theory, the cumulative effects of ecosystem-service degradation could exert a dampening effect on human well-being at the global scale without reversing positive trends in well-being. Although trends in well-being have risen in conjunction with food production, there may be a threshold at which the mounting costs associated with losses of other services outweigh further gains in well-being from additional food production. For example, in contrast to some multifunctional food production systems, many industrial food production systems in which the HDI continues to rise have become depopulated of human communities, have suffered decreased water quality, have lost many regulating ecosystem services and biodiversity, and are no longer areas of cultural or recreational importance (Brouwer et al., 2008). Net human well-being could theoretically be higher in these areas if food production were achieved without degrading these other services; however, this dampening effect is difficult to demonstrate at large scales.

Regionally, there is ample evidence for this dampening effect:

… [A] significant portion of the global burden of ill health is attributable to degraded land, water, and air; for example, 8% to 10% of malnutrition cases may be attributable to land degradation (Smith et al. 1999). Other studies state that as much as 40% of world deaths are due to environmental degradation, although the term “environmental” is used in the broadest sense to include all forms of pollution and some lifestyle choices (Pimentel et al. 2007). Environmental health scientists suggest that in many parts of the world, the environmental carrying capacity has been exceeded, and people in these areas will suffer from crop shortages caused by erosion and other forms of soil degradation, fish shortages, health impacts from poor sanitation and lack of drinking water, and conflict over resources (McMichael 1997). It is likely that net human well-being could be higher if these issues were better managed; however, at present we do not see a clear effect of these human well-being trends in national or global data sets.

The conclusion is a bit surprising, because it implies something about the contribution of regional effects to the global metric:

… [A]vailable evidence suggests that the benefits of food production currently outweigh the costs of declines in other ecosystem services at the global scale, and that this is a strong contributing factor to the environmentalist’s paradox. However, we also found considerable evidence at smaller scales that the loss of supporting and regulating services can have significant direct effects on human well-being (e.g., through increased floods), as well as indirect effects through impacts to food production.

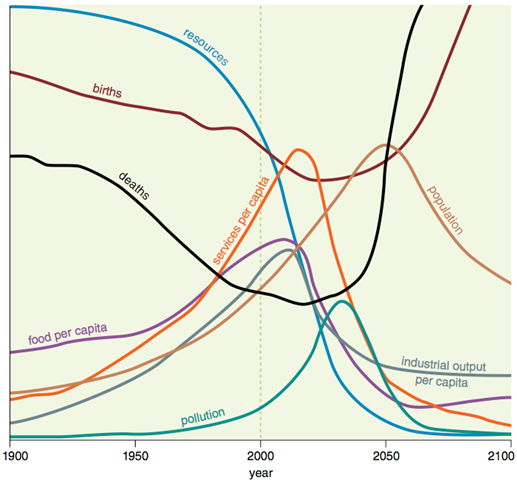

What’s the “glue” that holds the global system together as regional systems fail? Presumably the hyper-globalized economy is capable of smoothing the regional craters in the HDI curve, but for how long?  Technology and social innovation have decoupled human well-being from ecosystem degradation This argument is popular with the cornucopians: human ingenuity is infinitely substitutable for any depleted resource or service. Against this, we have the Limits To Growth study, which has shown pretty remarkable fidelity with reality since the simulations were run in 1972. The BioScience paper concludes that increased technological efficiency has not reduced societies’ use of ecosystem services but might in the future.

Technology and social innovation have decoupled human well-being from ecosystem degradation This argument is popular with the cornucopians: human ingenuity is infinitely substitutable for any depleted resource or service. Against this, we have the Limits To Growth study, which has shown pretty remarkable fidelity with reality since the simulations were run in 1972. The BioScience paper concludes that increased technological efficiency has not reduced societies’ use of ecosystem services but might in the future.

Despite these large gains in efficiency, humans’ overall use of ecosystem services has not declined, and demand is in fact growing for 80% of the services investigated by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA 2005). Growth in demand has more than kept pace with improvements in efficiency … the increasing efficiency with which we are able to benefit from provision of ecosystem services suggests that there is a potential for reducing our vulnerability to future ecosystem service losses, but this has yet to occur and may depend on our ability to curb the rising global consumption of resources.

Not much help for the cornucopian argument. Also interesting is the observation that demand for ecosystem services is actually growing, presumably because human population growth is overwhelming efficiency improvements. There is a time lag between ecosystem service degradation and impacts to human well-being Desdemona favors this hypothesis. It argues that humans “have yet to see global consequences to human well-being as a result of ecosystem service decline because of a time lag between the accumulating effects of human transformations of ecosystems and the impact of these changes on human well-being.” In other words, we’re living on borrowed time. The authors also favor this hypothesis, but admit that the evidence is weak:

… [A]nthropogenically driven ecological change has substantial and novel impacts on the biosphere. These changes present new challenges to humanity. The existence of a time lag between the destruction of natural capital and the decline in ecosystem service production provides an explanation of the environmentalist’s paradox, but uncertainty about the duration, strength, and generality of this lag prevents us from providing strong support for this hypothesis. However, evidence of past collapses and of declines in natural capital does mean that this hypothesis cannot be rejected.

When will we begin to see the impacts on a global scale, i.e., when (if ever) will the HDI curve begin to deflect downward? It may be Desdemona’s imagination, and you’d need to do some rigorous curve-fitting to support the idea, but eyeballing the HDI curve, it seems to be approaching a plateau, with a Limits to Growth-style inflection point looming. In the following graph, the three Limits to Growth curves that should be peaking about now are Food per Capita (violet), Industrial Output (gray), and Services per Capita (orange).

| The original projections of the limits-to-growth model examined the relation of a growing population to resources and pollution, but did not include a timescale between 1900 and 2100. If a halfway mark of 2000 is added, the projections up to the current time are largely accurate, although the future will tell about the wild oscillations predicted for upcoming years. Hall and Day, Jr, 2009 |

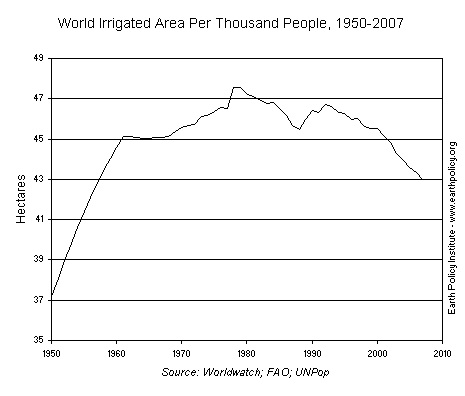

If we accept the Limits to Growth simulations, we can expect HDI to peak any time now, since that’s about when Food per Capita peaks. We know of some other significant peaks that have passed, all of which should contribute to a downward deflection in HDI, for example, in the amount of irrigated land per thousand people:

| World Irrigated Area Per Thousand People, 1950-2007. FAO / UNPop via Grist |

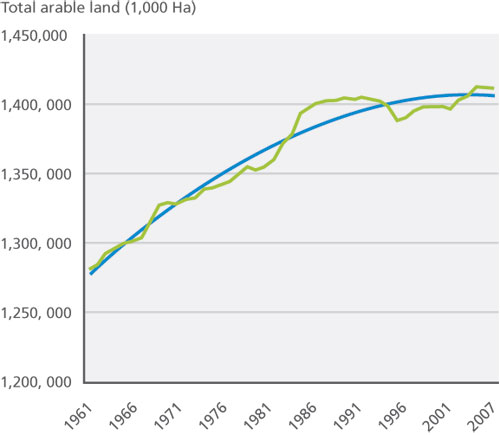

The total area of arable land appears to have reached a plateau:

| Total Arable Land, 1961-2007. Arable land expansion has slowed down substantially in the last 50 years. This implies that much of the best arable land is already in use. landcommodities.com |

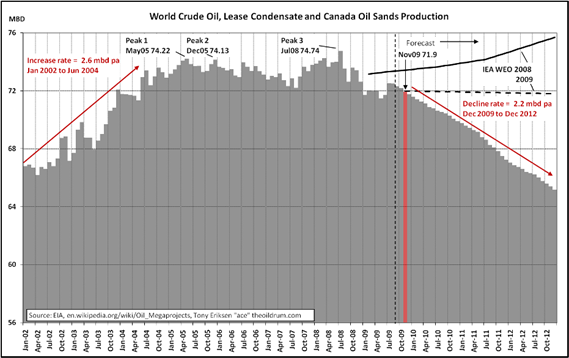

And, of course, world oil production appears to have peaked in May 2005.

| World Oil Production to 2012. Oil includes crude oil, lease condensate and oil sands. The Oil Drum |

The folks at The Oil Drum have collected a few more interesting peaks, such as those in US wages and consumer credit. In the face of these and other peaks, it seems highly likely to Desdemona that an inflection point in HDI is near, but like any pragmatic prophet of doom, can’t put a date on it. Ciara Raudsepp-Hearne, Garry D. Peterson. Maria Tengo, Elena M. Bennett Tim Holland, Karina Benessaiah, Graham K. Macdonald, And Laura Pfeifer, “Untangling the Environmentalist’s Paradox: Why Is Human Well-being Increasing as Ecosystem Services Degrade?” [abstract] [pdf], BioScience, September 2010, Vol. 60, No. 8, Pages 567–589 , DOI 10.1525/bio.2010.60.8.1

I think it just means we still have sufficient fossil fuel energy available at the moment, which can be substituted for a remarkable number of other ecological inputs which are in decline. We can grow food in sterile soils and transport it anywhere. We can create fresh water from salt water. We can live in climate controlled buildings. Fossil fuel makes us possible. Without it….

Ergo,

When the earth

is completely dead,

we humans

will be entirely happy.

.

I think this is missing the most basic of all inputs: energy itself.

Energy (by definition) is the capacity to do work. More energy == greater capacity for work. So, as the earth as been stripped of its resources by the industrial system, this system has used energy to do it, and primarily from fossil fuels.

Therefore, if alternatives to fossil fuel are not found in adequate volumes, then the total energy content of the civilisation will decrease and then you will see declines in the HDI.

The declines will be staved off through optimisation practices, but eventually those too will fail, and at that point people will simply have to make "other arrangements". These arrangements will necessarily be on a different axis of consideration from the HDI and therefore, the HDI will see this as suboptimal and therefore a lower HDI value will follow.

In reverse: if humans had access to arbitrarily large amounts of energy, they could do utterly crazy stuff like strain gold out of sea water or give everyone a luxury vehicle to drive. The environment would continue to suffer, but with more energy, humans could apply that to materials that would mitigate these problems.

So, I would scrap the analysis above and look directly at energy states and volumes to figure out this particular conundrum.

Quite a treatise. I put a date on it:

2011.

Crash.