By FELICITY BARRINGER

By FELICITY BARRINGER

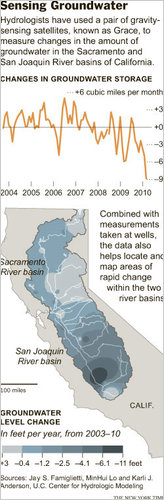

30 May 2011 IRVINE, Calif. — Scientists have been using small variations in the Earth’s gravity to identify trouble spots around the globe where people are making unsustainable demands on groundwater, one of the planet’s main sources of fresh water. They found problems in places as disparate as North Africa, northern India, northeastern China and the Sacramento-San Joaquin Valley in California, heartland of that state’s $30 billion agricultural industry. Jay S. Famiglietti, director of the University of California’s Center for Hydrologic Modeling here, said the center’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment, known as Grace, relies on the interplay of two nine-year-old twin satellites that monitor each other while orbiting the Earth, thereby producing some of the most precise data ever on the planet’s gravitational variations. The results are redefining the field of hydrology, which itself has grown more critical as climate change and population growth draw down the world’s fresh water supplies. Grace sees “all of the change in ice, all of the change in snow and water storage, all of the surface water, all of the soil moisture, all of the groundwater,” Dr. Famiglietti explained. Yet even as the data signals looming shortages, policy makers have been relatively wary of embracing the findings. California water managers, for example, have been somewhat skeptical of a recent finding by Dr. Famiglietti that from October 2003 to March 2010, aquifers under the state’s Central Valley were drawn down by 25 million acre-feet — almost enough to fill Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir. Greg Zlotnick, a board member of the Association of California Water Agencies, said that the managers feared that the data could be marshaled to someone else’s advantage in California’s tug of war over scarce water supplies. “There’s a lot of paranoia about policy wonks saying, ‘We’ve got to regulate the heck out of you,’ ” he said. … While Dr. Famiglietti says he wants no part of water politics, he acknowledged that this might be hard to avoid, given that his role is to make sure the best data about groundwater is available, harvesting and disseminating all of the information he can about the Earth’s water supply as aquifers dry up and shortages loom. “Look, water has been a resource that has been plentiful,” he said. “But now we’ve got climate change, we’ve got population growth, we’ve got widespread groundwater contamination, we’ve got satellites showing us we are depleting some of this stuff. “I think we’ve taken it for granted, and we are probably not able to do that any more.” …

Groundwater Depletion Is Detected From Space

By FELICITY BARRINGER