West Nile virus outbreak worst ever in U.S. – Outbreaks may get worse as climate gets hotter, experts say

By Jon Bardin

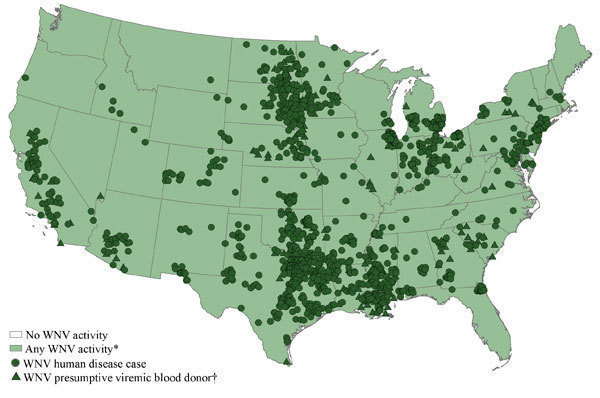

10 September 2012 (Los Angeles Times) – West Nile virus has caused symptoms in at least 1,993 Americans and killed 87 so far this year. And it’s unlikely that this virus, which humans contract from infected mosquitoes, will be getting any less dangerous in the near future. Though the CDC believes that this year’s caseload has probably peaked, a group of public health officials writing in the new edition of Annals of Internal Medicine explains why West Nile has been so deadly this year. West Nile virus made its first appearance in the United States in 1999, when the virus, which had previously affected people in Uganda, Algeria and Romania, arrived in New York City. This year is shaping up to be the worst in a decade, particularly in Texas, which has reported nearly half of all cases. Things have gotten so bad that officials in Dallas had to blanket the city in anti-mosquito pesticide for the first time in 45 years. Why the sudden epidemic? Catherine M. Brown and Dr. Alfred Demaria Jr., of the Massachusetts Bureau of Infectious Disease argue in Annals that the most likely explanation is that the extreme weather patterns we have seen this year — in particular, abnormally high temperatures across the country — may have led to the outbreak. High temperatures increase the rate of mosquito breeding, as well as the rate of development of viruses within those mosquitoes. So this year’s weather may have not only increased the number of West Nile-carrying mosquitoes, but also raised the likelihood that a new strain would arise, which would cause the disease to spread more rapidly. While there is no firm evidence as yet that a new strain has emerged, Brown and Demaria point to an observed increase in dead birds. (Birds also catch the virus from mosquitoes, and infected birds can transmit it to the mosquitoes that bite them.) There is no effective treatment or vaccine for West Nile virus. So the best thing for people to do, write Brown and Demaria, is to prevent mosquitoes from infecting us in the first place: “Mosquito prevention messages must be unrelenting, directed at personal protective behaviors (avoidance, repellents, clothing) and reduction of breeding sites. The public must be constantly prodded, with a balance of sensible precautions and serious awareness of the possibility for severe disease.” The potential role of environmental factors in this year’s outbreak also raises a discomforting idea: That changes in climate may lead to unpredictable changes in disease propagation. If we are likely to have more extremely hot, drought-filled summers in the future, we would also seem more likely to have more serious outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases. As Brown and Demaria write: “The interplay of heat, drought, human habitats, increased mosquito populations, and enhanced viral development all act in concert to increase the force of transmission. At least that’s the theory. The truth of what lies behind the resurgence of [West Nile virus] activity this year will take time to uncover.”

West Nile virus may get worse as climate gets hotter, experts say

By Thomas H. Maugh II

5 September 2012 This year’s outbreak of West Nile virus is the worst since the illness was first observed in the United States in 1999, officials from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Wednesday. The number of confirmed cases rose by 25% last week to 1,993 — although only an estimated 2% to 3% of cases are reported to the government. Those are generally the most serious infections: Most people who contract the virus do not develop severe symptoms, and many never even know they were infected. The most common symptoms are a fever and neck stiffness. Severe cases can lead to encephalitis or meningitis. The number of deaths rose to 87, up from 65 a week ago. The death total seems unlikely to break the record of 260 set in the 2002-03 season, however. Almost half of the reported cases (888) are in Texas, which has seen 35 deaths from the disease. Other states with high rates include Mississippi, South Dakota, Oklahoma, and Louisiana. California has had 55 confirmed cases and two deaths. The outbreak probably peaked in August, CDC officials said, although the number of new cases will most likely continue to grow until October – at least in part because of lags in reporting them. Officials said a mild spring, very hot summer and heavy rains in some areas probably contributed to this year’s increases.