Great Barrier Reef coral seeing ‘major decline’ – Starfish moving ‘in massive waves down the Reef like a plague’

By Miguel Llanos, NBC News

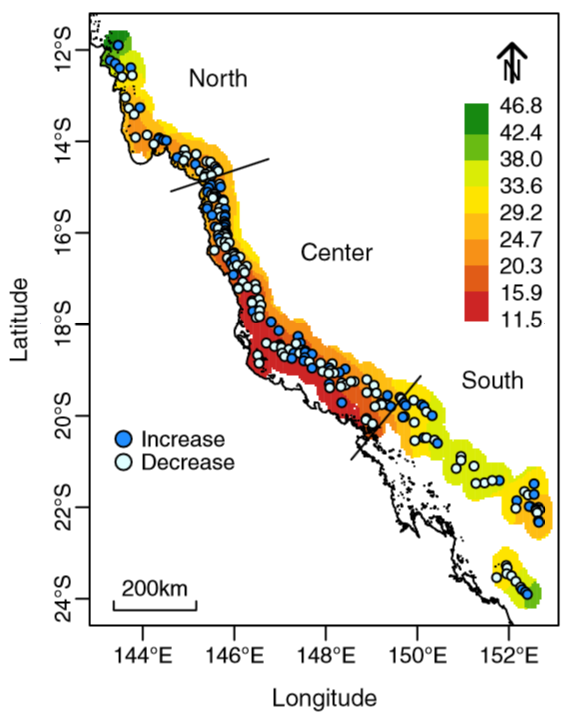

1 October 2012 Calling it the most extensive review of how coral on Australia’s Great Barrier Reef is faring, scientists on Monday reported some alarming news: The amount of coral covering reefs there has been cut in half since 1985 and will likely continue to decline unless steps are taken to at least attack the easiest of several factors. “We show a major decline in coral cover from 28 percent to 13.8 percent” of the entire system, the experts wrote after reviewing 2,258 surveys of 214 reefs within the marine sanctuary. “Two-thirds of that decline has occurred since 1998,” they added. John Bruno, a coral expert who was not part of the study, called the findings “really grim” and reflecting loss even higher than deforestation in the tropics, a topic that generally gets much more attention. In 2007, we first sounded the alarm that the Great Barrier Reef, and Pacific reefs in general, were not as pristine and resilient as a lot of people wanted to believe,” Bruno, a marine biology professor at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, told NBC News. “But still, this is really shocking to me.” “This is a really high rate of loss for an entire region,” he added. “This is just nuts and it appears to have been sustained over the last five to 10 years. Just mind blowing. I really didn’t expect this.” The researchers estimated that tropical storms, coral predation by crown-of-thorns starfish and coral bleaching accounted for 48 percent, 42 percent and 10 percent of the respective estimated loss in coral cover. Coral bleaching, whereby coral expels the tiny single-celled algae inside that provide color, is triggered by stress such as warm seas or pollution. The experts didn’t have much faith in quick actions to counter warming seas, storms and bleaching, but they believe it might be possible to reduce starfish populations. They based their hope on evidence that starfish are linked to poor water quality, and the fact that the northern Great Barrier Reef, which has little starfish predation, showed no overall decline. Nutrient-rich waters stimulate plankton, which starfish larvae thrive on, the experts noted, and if fertilizer and other nutrient-rich pollution in the water is cleaned up, starfish populations would decline and coral cover could increase by nearly a percentage point a year, they estimated. “Survival of the plankton-feeding larvae … is high in nutrient-enriched flood waters, whereas few larvae complete their development in seawater with low phytoplankton concentrations,” the experts wrote. Bruno, for his part, said the impact of starfish on the reef is “striking,” with the carnivores actually eating away at coral. “They are huge and scary beasts,” he said, citing outbreaks in which the starfish “move in massive waves down the Great Barrier Reef like a plague.” The study’s authors predicted that without intervention the coral cover on the reef will probably decline up to 10 percent in the next 10 years. The study by experts at the Australian Institute of Marine Science and the University of Wollongong was published in the peer-reviewed Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. […]

Great Barrier Reef coral seeing ‘major decline,’ scientists report