Arctic warming and our extreme weather: New study finds no clear link

By Jason Samenow

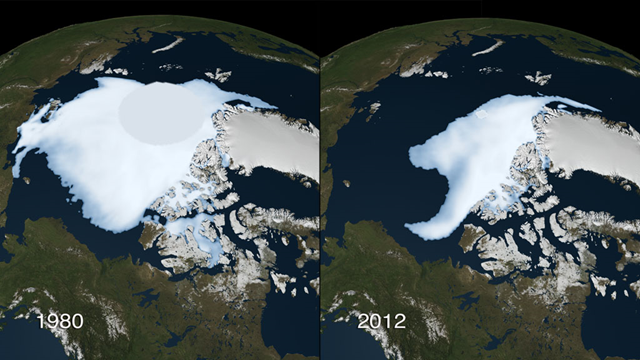

19 August 2013 (Washington Post) – Is the dramatic decline of Arctic sea ice, spurred by manmade global warming, making the weather where we live more extreme? Several recent studies have made this claim. But a new study finds little evidence to support the idea that the plummeting Arctic sea ice has meaningfully changed our weather patterns. The research, published today in Geophysical Research Letters, says links between declining Arctic sea ice and extreme weather are “an artifact of the methodology” and not real. Earlier work, suggesting a connection between the disintegrating Arctic ice and weather mania in the mid-latitudes, is intriguing. It is based on the idea that the jet stream – the river of high altitude winds that steers our storms and positions cold snaps and heat waves – is slowing down and weakening due to a pronounced warming in the Arctic compared to other places, a phenomenon known as Arctic amplification. Rather than zipping right along a straight path, a more listless jet stream is now prone to straying so the theory goes. “Just as a river of water tends to meander when it reaches the gentle slopes of coastal plains, a weaker jet stream tends to have steeper north-south waves,” explained Rutgers University atmospheric professor Jennifer Francis, in a guest blog post here at CWG. “The slower the waves move, the longer the weather associated with them will persist.” When the jet stream gets stuck, trouble ensues: a storm dumps copious rains in the same place, a heat wave stagnates, and a drought grows more severe, for example. Francis, a leading scientist of some of the research linking Arctic amplification and more extreme weather patterns in the mid-latitudes, said the unusual path of Superstorm Sandy may have been a consequence of the connection. The record loss of Arctic ice last fall favored a “block” or extreme slowing in the jet stream over Greenland that pushed Sandy towards the Jersey shore Francis contends. “The block was what scared [Sandy] into the west,” Francis told the New Jersey Star Ledger. “It’s a very, very unusual pattern for a hurricane to take…” But the new research by Colorado State professor Elizabeth Barnes, which examined the waviness of the jet stream over the period 1980-2011, found no changes in its speed and no signs of increased blocking. “We conclude that the mechanism put forth by previous studies … that amplified polar warming has lead to the increased occurrence of slow-moving weather patterns and blocking episodes, is unsupported by the observations,” Barnes writes. While Barnes’ study did not identify jet stream changes in the last 30 years, the most rapid decline in Arctic sea ice has occurred in the last decade – so it’s possible the Barnes’ analysis smoothed over a very recent change in jet stream behavior. A NOAA-led study last year noted a change in Arctic winds beginning in 2007, which may have signaled the point at which this mechanism became observable. “This shift demonstrates a physical connection between reduced Arctic sea ice in the summer, loss of Greenland ice, and potentially, weather in North America and Europe,” said James Overland, of NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory and study lead author. Since the sea ice and jet stream mechanism was first proposed, the research community has been somewhat divided on its presence. “[W]ith respect to the Arctic connection, I don’t believe it,” University Center for Atmospheric Research (UCAR) scientist Kevin Trenberth told the NY Times’ Andrew Revkin in the aftermath of Sandy and possible links. “… the null hypothesis has to be that this is just “weather” and natural variability.” [more]

Arctic warming and our extreme weather: no clear link new study finds

I'm not sure I would want to publish a paper saying that I failed to find something.

The study ended in 2011 – recent changes have been more radical… this seems like a way to skew data.