The Big Lie behind Japan’s ‘scientific’ whaling program

By Peter Wynn Kirby

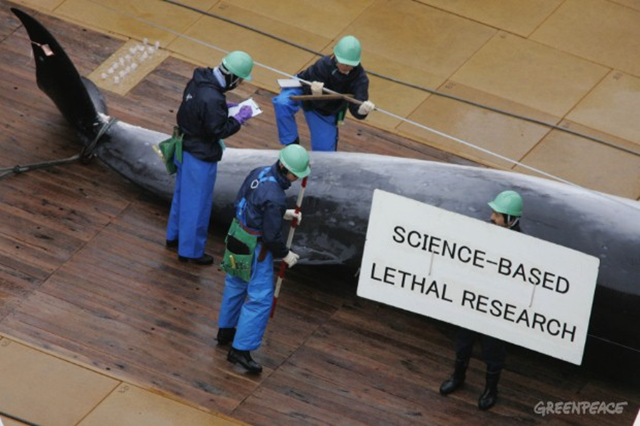

13 October 2014 TOKYO (The New York Times) – The International Court of Justice’s decision last March to prohibit Japan’s annual whale hunt in Antarctic waters was greeted by many as an historic step against a reprehensible practice. Yet last month, despite the enormous diplomatic toll, Japan vowed to continue its whaling activities under a controversial research program of dubious scientific merit. Japan’s determination may seem puzzling, but only if you assume its whaling activities are about science, or that its purportedly scientific whaling is a cover for commercial whaling. In fact, Japan’s pro-whaling stance isn’t really about whales at all; instead, it is about ensuring access to other fishing resources. Japan’s so-called research whaling program is far from scientific: Thanks to unprofessional methodology and sloppy standards, its findings are widely regarded as risible. Some 3,600 whales have been slaughtered since 2005, but Japan’s Institute for Cetacean Research (I.C.R.), the de facto government entity that oversees the country’s whaling program, has only two peer-reviewed scholarly articles to show for it. And much robust testing doesn’t even require killing whales. Meanwhile, the market for whale meat in Japan has slumped considerably. Whaling proponents claim the practice helps safeguard Japan’s culinary heritage against Western cultural imperialism. But survey after survey shows that outside a handful of small whaling communities, most Japanese regard whale meat with indifference, if not disgust. They eat less than 24 grams per capita annually. Thousands of tons of frozen whale steaks and whale bacon languish unwanted in expensive cold storage. As a result, the I.C.R., once largely funded by the sale of whale meat, is now claiming more taxpayer money. These inefficiencies result from a policy that hides its true motives: If the Japanese government adamantly defends its marginal whaling rights, it is because it fears encroachment on its critical fishing activities. This concern is not only a point of cultural pride and a commercial necessity; it is also perceived as a strategic imperative. Japan catches several million tons of seafood a year and is the third-largest importer of seafood, behind the European Union and the United States. Japanese eat more fish per capita than the people of any other industrialized nation. The problematic use of whaling to safeguard fisheries dates back to the early 1980s and discussions about an international moratorium on commercial whaling. With the negotiations stalled because Japan opposed the idea of a ban, the American government threatened to limit Japanese ships’ access to fishing stocks in United States waters unless Japan withdrew its objection. Japan complied in 1986, privileging fisheries over whaling. But the United States then curtailed Japan’s access to American fish stocks anyway. And in 1987 Japan announced it would resume whaling under the controversial pseudo-scientific program still in place today. Since then, more hidebound Japanese bureaucrats, particularly in the Fisheries Agency, have feared that giving ground on whaling would undermine Japan’s ability to harvest other seafood. Joji Morishita, now Japan’s commissioner to the International Whaling Commission, let slip this rationale in an interview in 2000. He said he worried that conceding too much would “set a precedent” and that “once the principle of treating wildlife as a sustainable resource is compromised, our right to exploit other fish and animal products would be infringed upon.” [more]

The Big Lie Behind Japanese Whaling

You see, it's all AWFUL! And you freaks want to SAVE this hideous mess? Let it go! You can't fix this existence, it's broken at the core.