Global biodiversity report shows “catastrophic decline” in wildlife populations – “In just my lifetime, 50 years, we’ve seen a decline of 73 percent in the average size of these wildlife populations”

By Molly McCrea

18 October 2024

(CBS News) – A shocking new report on global biodiversity is detailing what it calls “a catastrophic decline” in wildlife populations ahead of a major international conference on biodiversity.

On Monday, 21 October 2024, the United Nations will convene a two-week conference in Cali, Colombia called COP16. On the agenda are climate change and the protection of life. But hanging over this meeting is a new report by the World Wide Fund for Nature (formerly the World Wildlife Fund). The 2024 Living Planet Report details “a catastrophic 73 percent decline in the average wildlife populations over just 50 years.”

The concern is centered at points around the world – from the grassy fields in the Serengeti to the urban jungles of the San Francisco Bay Area. Creatures big and small are under threat.

“That means in just my lifetime, 50 years, we’ve seen a decline of 73 percent in the average size of these wildlife populations,” noted Dr. Robin Freeman, global biodiversity expert with the Zoological Society of London.

Among the biggest threats are humans and a warming planet. Both are leading to an accelerating change that will make it impossible for species to successfully adapt.

“Species are very often exquisitely tuned to local environments that have taken thousands to millions of years through co-evolution to kind of establish and create the selection across their genome as to what features are going to survive,” noted Stanford biology professor Dr. Elizabeth Hadly. “When we are changing things so rapidly, we unravel those connections, extinction happens in a heartbeat.”

Humans are encroaching into the critical habitats of multiple species and putting many ecosystems at risk, thereby threatening the planet’s biodiversity. The impacts are affecting the elephants in tropical forests, the hawksbill sea turtles off the Great Barrier Reef, and even the migrating birds that pass through the Bay Area.

“Most of our native birds need a lot of biodiversity in the plants and the insects in order to survive,” explained Dr. Katie LaBarbera, senior biologist and science director for the Land Bird Program at the San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory, who noted how around the world, some bird populations are in decline.

In addition to birds, some fish are in trouble. According to the WWF report, in California, the number of winter-run Chinook salmon dropped 88 percent since 1970. The Shasta Dam blocked off access to their historical spawning ground, while climate change threatens the Sacramento River – an important migration route.

Chief Caleen Sisk, spiritual leader of the Winnemem Wintu Tribe, and tribal members are working with Maori people of New Zealand and federal fish biologists to return Chinook salmon to the McCloud River and to find passage for them.

In the 19th century, millions of salmon eggs from the McCloud River were exported to 30 states and 14 different countries to create new salmon runs. New Zealand was the only location where the new run thrived, and in 2005, the Māori invited the Winnemem Wintu to bring wild salmon eggs back home to the McCloud.

“The water system here in California really are dependent on how we take care of the salmon,” said Sisk. “If the salmon survive, people will survive. If we want to drain the rivers and rename them as warm water rivers people will also suffer.”

These Bay Area experts say protecting the planet’s wildlife is an urgent wake-up call that no one should ignore.

“Biodiversity can never be recreated,” said Hadly. “It is what we rely on for our food, for our medicine, for our housing. It is so critically important for our humanity.”

“The bits of nature that we have around us are really precious and we’re not going to save them if we don’t first really appreciate them,” added LaBarbera.

“I wish that we could educate everyone about our salmon,” said Sisk. “They’re not just a food to eat. They dig down into the gravel and they let all the silt go out to the sea and they let that river breathe into the groundwater systems.”

The hope with this upcoming conference is that nations will agree to new standards on how to restore nature and halt the decline.

Global biodiversity report shows “catastrophic decline” in wildlife populations

2024 Living Planet Report: A System in Peril

18 October 2024 (WWF) – Nature is being lost – with huge implications for us all.

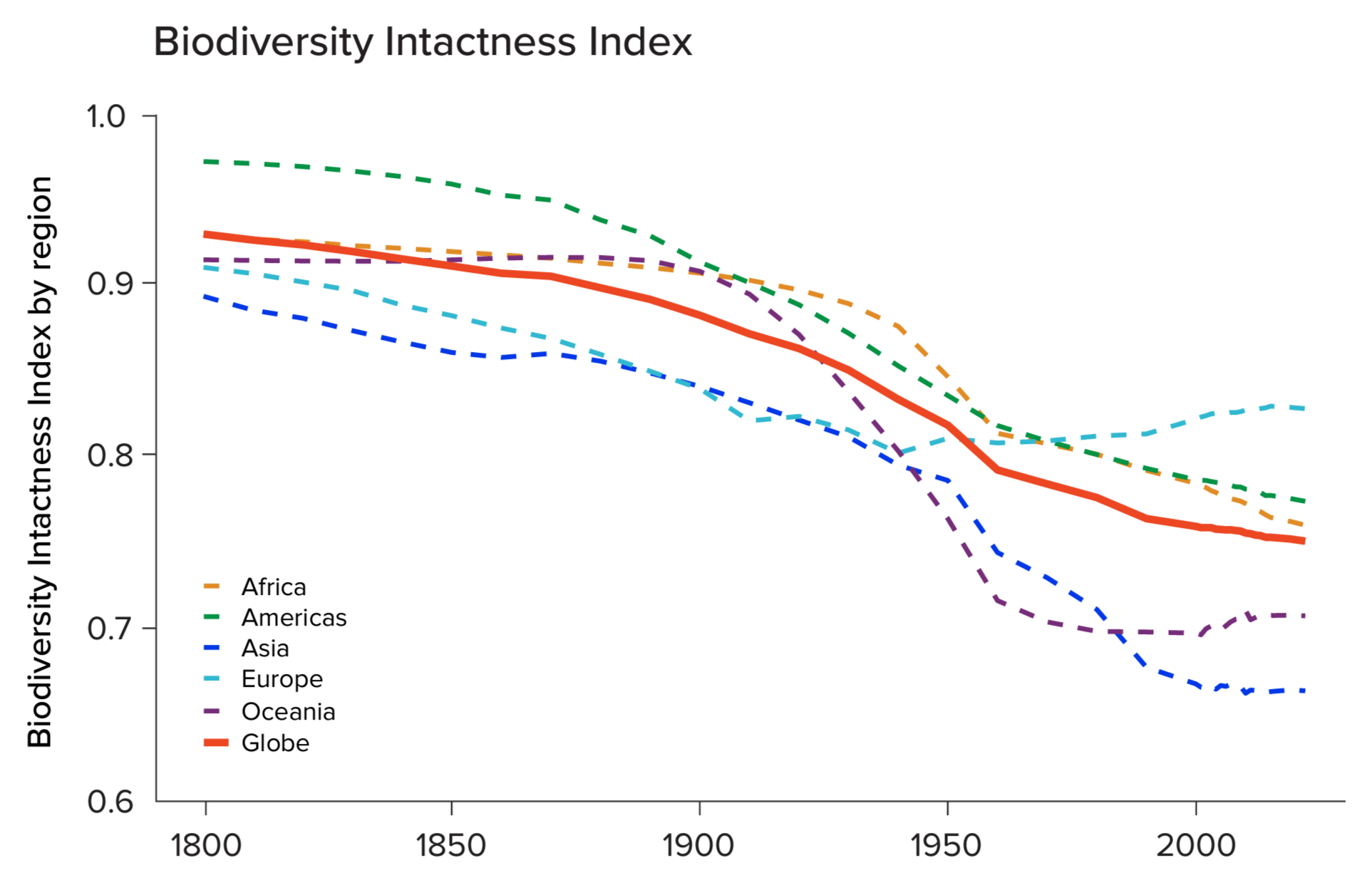

Biodiversity sustains human life and underpins our societies. Yet every indicator that tracks the state of nature on a global scale shows a decline.

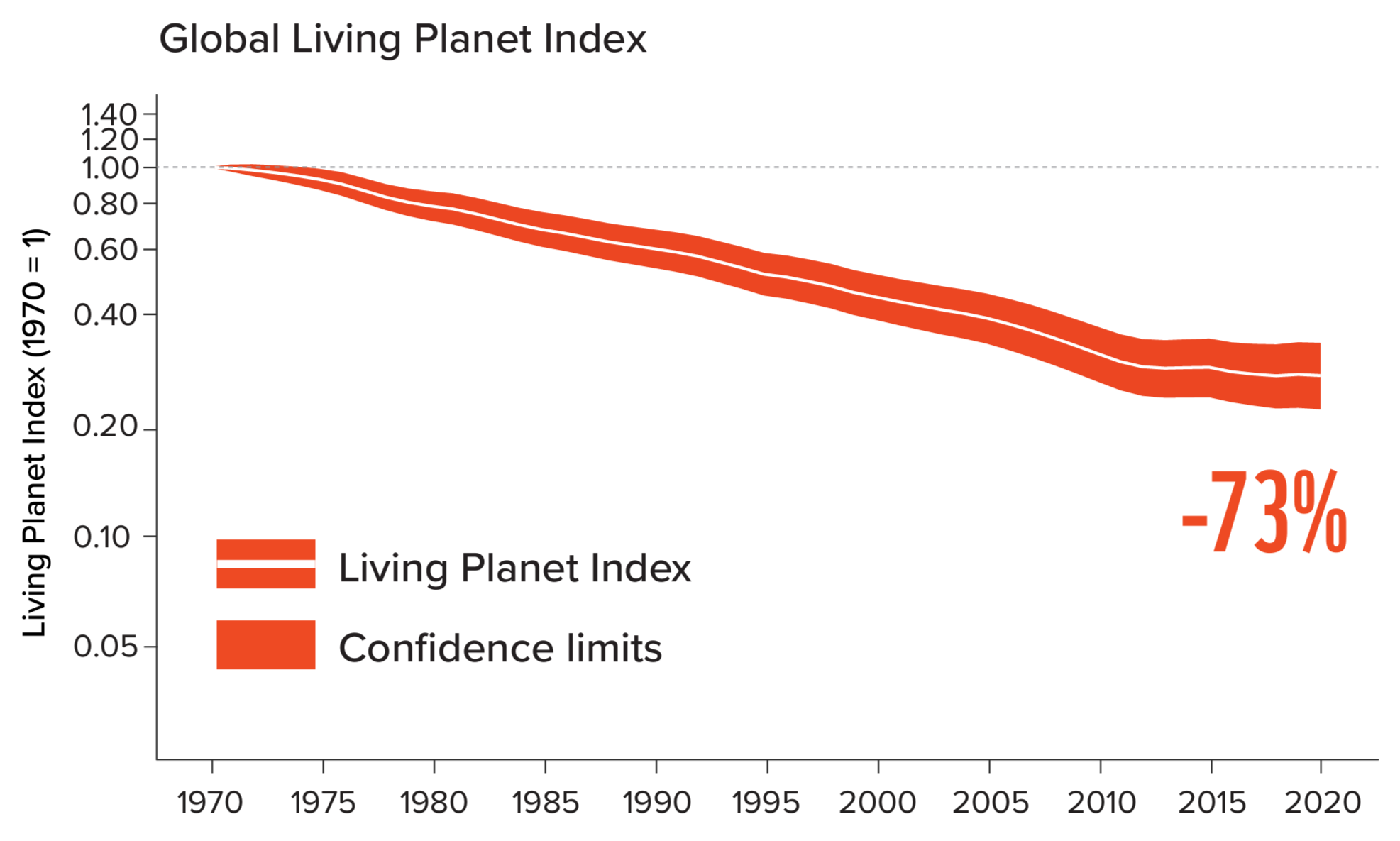

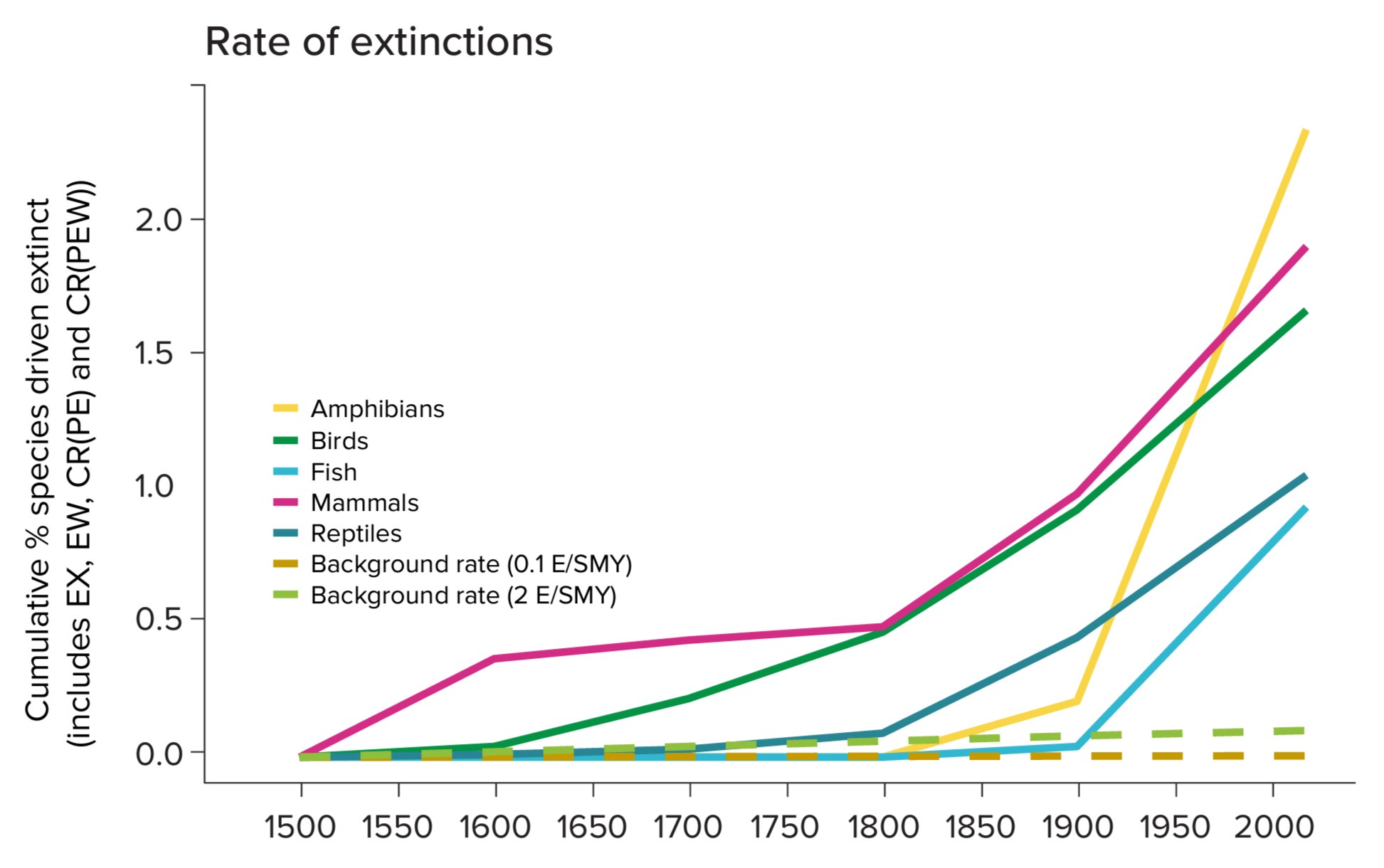

Over the past 50 years (1970–2020), the average size of monitored wildlife populations has shrunk by 73%, as measured by the Living Planet Index (LPI). This is based on almost 35,000 population trends and 5,495 species of amphibians, birds, fish, mammals and reptiles. Freshwater populations have suffered the heaviest declines, falling by 85%, followed by terrestrial (69%) and marine populations (56%).

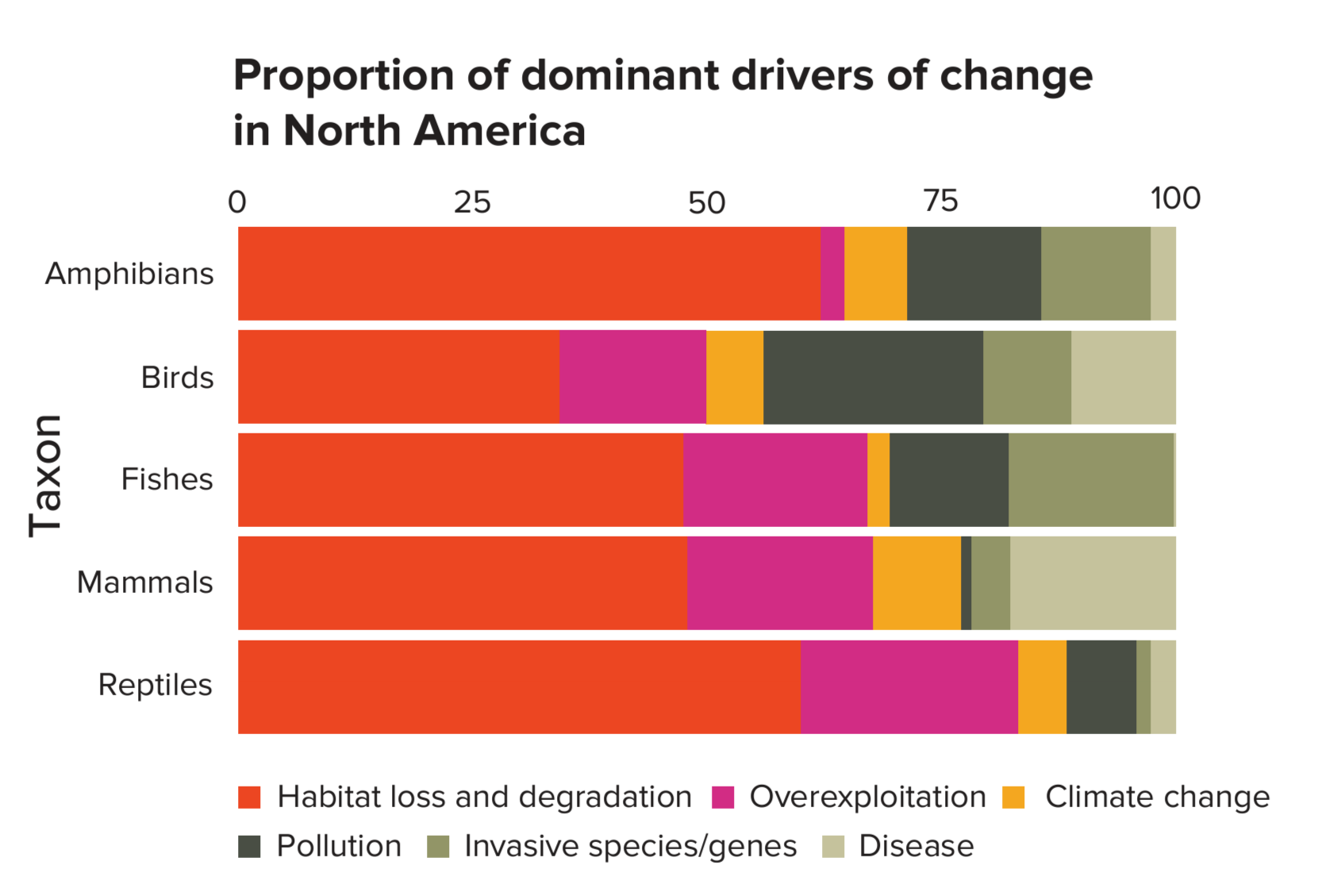

At a regional level, the fastest declines have been seen in Latin America and the Caribbean – a concerning 95% decline – followed by Africa (76%) and the Asia and the Pacific (60%). Declines have been less dramatic in Europe and Central Asia (35%) and North America (39%), but this reflects the fact that large-scale impacts on nature were already apparent before 1970 in these regions: some populations have stabilized or increased thanks to conservation efforts and species reintroductions. Habitat degradation and loss, driven primarily by our food system, is the most reported threat in each region, followed by overexploitation, invasive species and disease. Other threats include climate change (most cited in Latin America and the Caribbean) and pollution (particularly in North America and Asia and the Pacific).

By monitoring changes in the size of species populations over time, the LPI is an early warning indicator for extinction risk and helps us understand the health of ecosystems. When a population falls below a certain level, that species may not be able to perform its usual role within the ecosystem – whether that’s seed dispersal, pollination, grazing, nutrient cycling or the many other processes that keep ecosystems functioning. Stable populations over the long term provide resilience against disturbances like disease and extreme weather events; a decline in populations, as shown in the global LPI, decreases resilience and threatens the functioning of the ecosystem. This in turn undermines the benefits that ecosystems provide to people – from food, clean water and carbon storage for a stable climate to the broader contributions that nature makes to our cultural, social and spiritual well-being.

Dangerous tipping points are approaching

The LPI and similar indicators all show that nature is disappearing at an alarming rate. While some changes may be small and gradual, their cumulative impacts can trigger a larger, faster change. When cumulative impacts reach a threshold, the change becomes self-perpetuating, resulting in substantial, often abrupt and potentially irreversible change. This is called a tipping point.

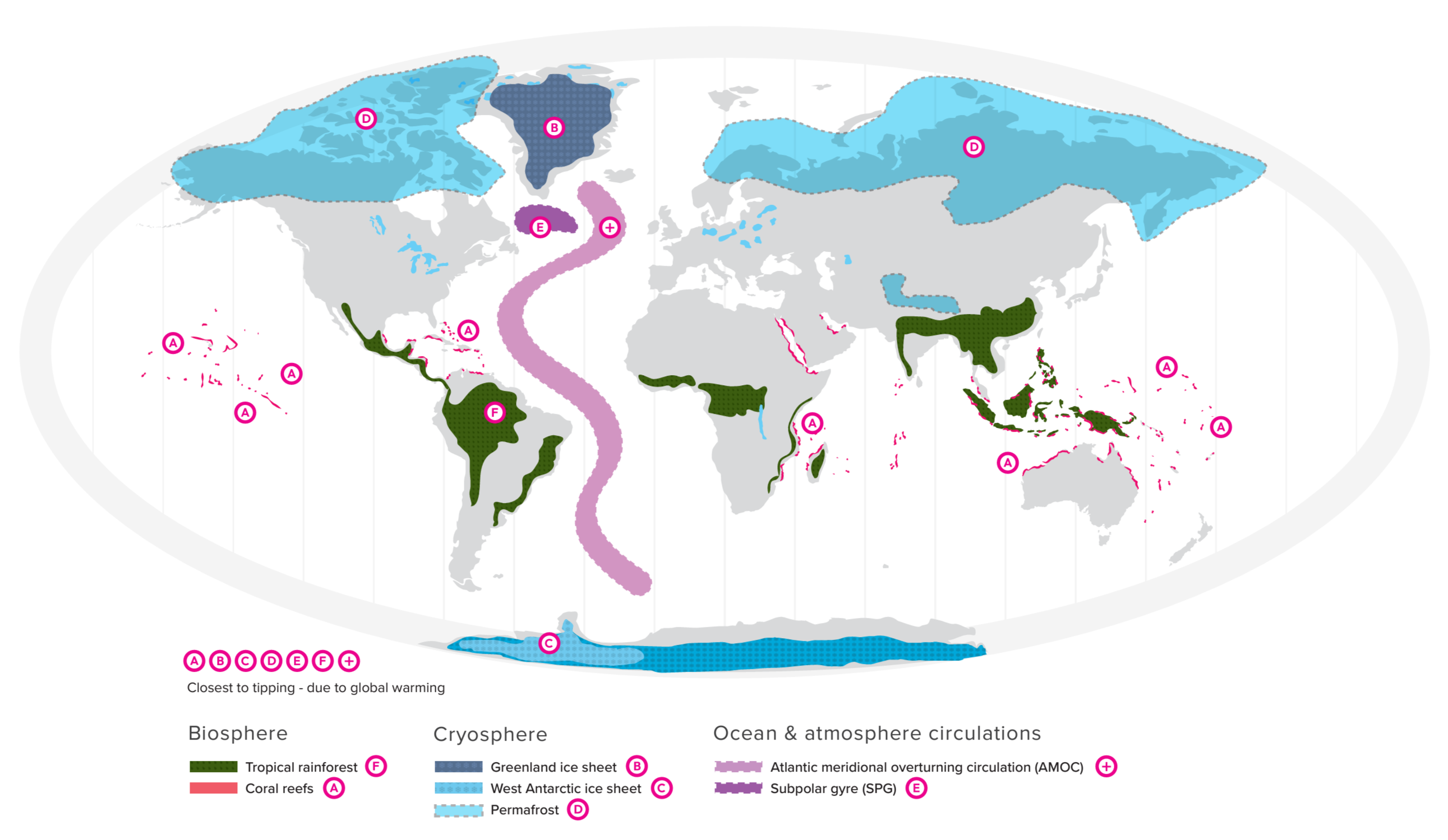

In the natural world, a number of tipping points are highly likely if current trends are left to continue, with potentially catastrophic consequences. These include global tipping points that pose grave threats to humanity and most species, and would damage Earth’s life-support systems and destabilize societies everywhere. Early warning signs indicate that several global tipping points are fast approaching:

In the biosphere, the mass die-off of coral reefs would destroy fisheries and storm protection for hundreds of millions of people living on the coasts. The Amazon rainforest tipping point would release tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere and disrupt weather patterns around the globe.

In ocean circulation, the collapse of the subpolar gyre, a circular current south of Greenland, would dramatically change weather patterns in Europe and North America.

In the cryosphere (the frozen parts of the planet), the melting of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets would unleash many metres of sea level rise, while large-scale thawing of permafrost would trigger vast emissions of carbon dioxide and methane.

Global tipping points can be hard to comprehend – but we’re already seeing tipping points approaching at local and regional levels, with severe ecological, social and economic consequences:

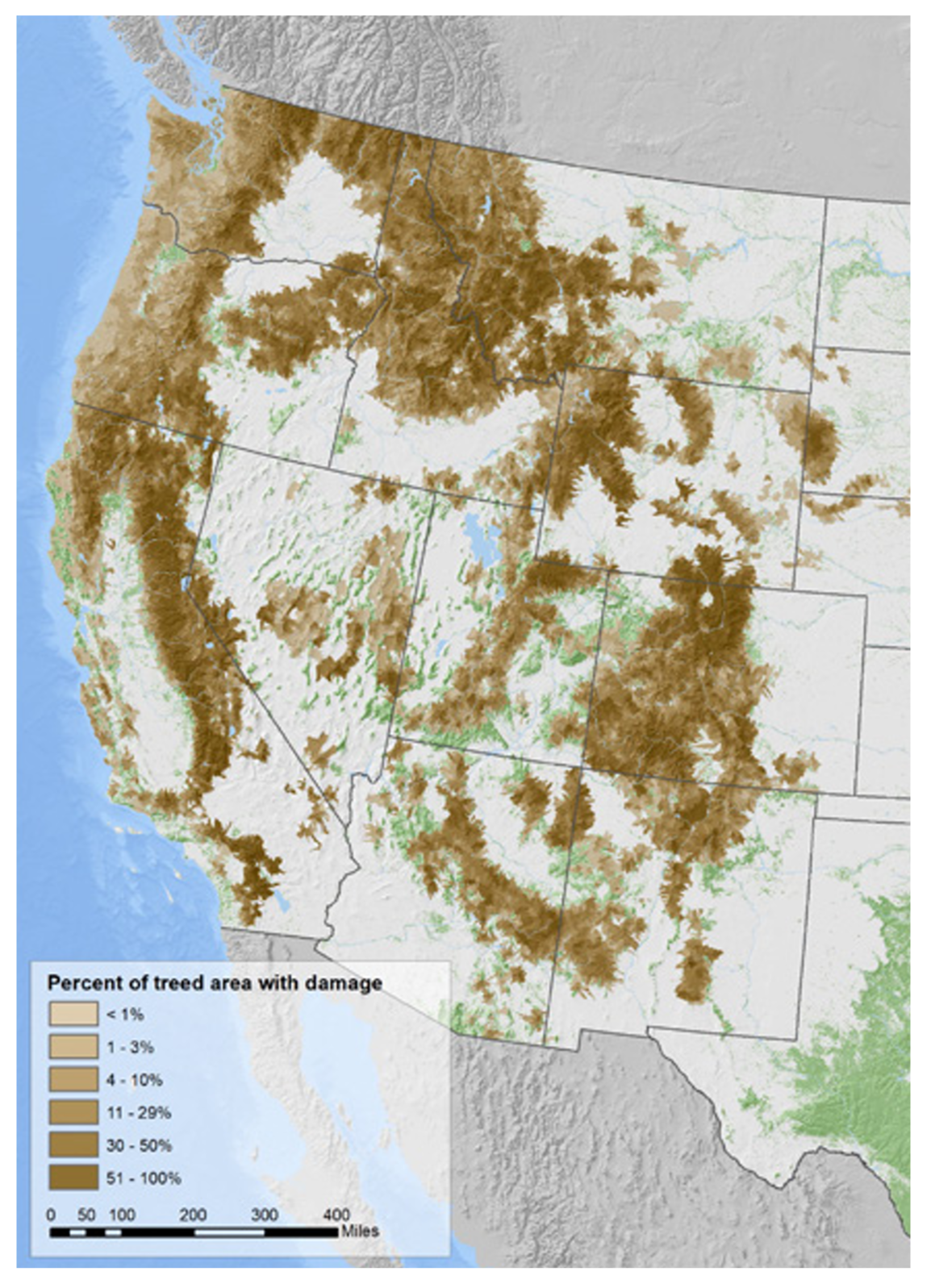

- In western North America, a combination of pine bark beetle infestation and more frequent and ferocious forest fires, both exacerbated by climate change, is pushing pine forests to a tipping point where they will be replaced by shrubland and grassland.

- In the Great Barrier Reef, rising sea temperatures coupled with ecosystem degradation have led to mass coral bleaching events in 1998, 2002, 2016, 2017, 2020, 2022 and 2024. Although the Great Barrier Reef has shown remarkable resilience to date, we will likely lose 70–90% of all coral reefs globally, including the Great Barrier Reef, even if we are able to limit climate warming to 1.5°C.

- In the Amazon, deforestation and climate change are leading to reduced rainfall, and a tipping point could be reached where the environmental conditions become unsuitable for tropical rainforest, with devastating consequences for people, biodiversity and the global climate. A tipping point could be on the horizon if just 20–25% of the Amazon rainforest were destroyed – and an estimated 14–17% has already been deforested.

In many cases, the balance is precarious – but tipping points can still be avoided. We have an opportunity to intervene now to increase ecosystem resilience and reduce the impacts of climate change and other stressors before these tipping points are reached.

We are falling short of our global goals

The nations of the world have set global goals for a thriving, sustainable future, including halting and reversing the loss of biodiversity (under the Convention on Biological Diversity, or CBD), capping global temperature rise to 1.5ºC (under the Paris Agreement), and eradicating poverty and ensuring human well-being (under the Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs). But despite these global ambitions, national commitments and actions on the ground fall far short of what’s needed to meet our targets for 2030 and avoid the tipping points that would make achieving our goals impossible. As things stand:

- Over half the SDG targets for 2030 will be missed, with 30 percent of them stalled or getting worse from the 2015 baseline.

- National climate commitments would lead to an average global temperature increase of almost 3°C by the end of the century, inevitably triggering multiple catastrophic tipping points.

- National biodiversity strategies and action plans are inadequate and lack financial and institutional support.

- Approaching climate, biodiversity and development goals in isolation raises the risk of conflicts between different objectives – for example, between using land for food production, biodiversity conservation or renewable energy. With a coordinated, inclusive approach, however, many conflicts can be avoided and trade-offs minimized and managed. Tackling the goals in a joined-up way opens up many potential opportunities to simultaneously conserve and restore nature, mitigate and adapt to climate change, and improve human well-being. [more]

2024 Living Planet Report: Executive Summary