Antarctica “doomsday glacier” could raise global sea levels by 10 feet – “Thwaites is really holding on today by its fingernails”

By Li Cohen

6

(CBS News) – The loss of a glacier the size of Florida in Antarctica could wreak havoc on the world as scientists expect it would raise global sea levels up to 10 feet. It’s already melting at a fast rate — and scientists say its collapse may only rapidly increase in the coming years.

The Thwaites Glacier is the widest on Earth at about 80 miles in width. But as the planet continues to warm, its ice, like much of the sea ice around Earth’s poles, is melting. The rapidly changing state of the glacier has alarmed scientists for years because of the “spine-chilling” global implications of having so much additional water added to the Earth’s oceans, sparking its nickname of the “doomsday glacier.”

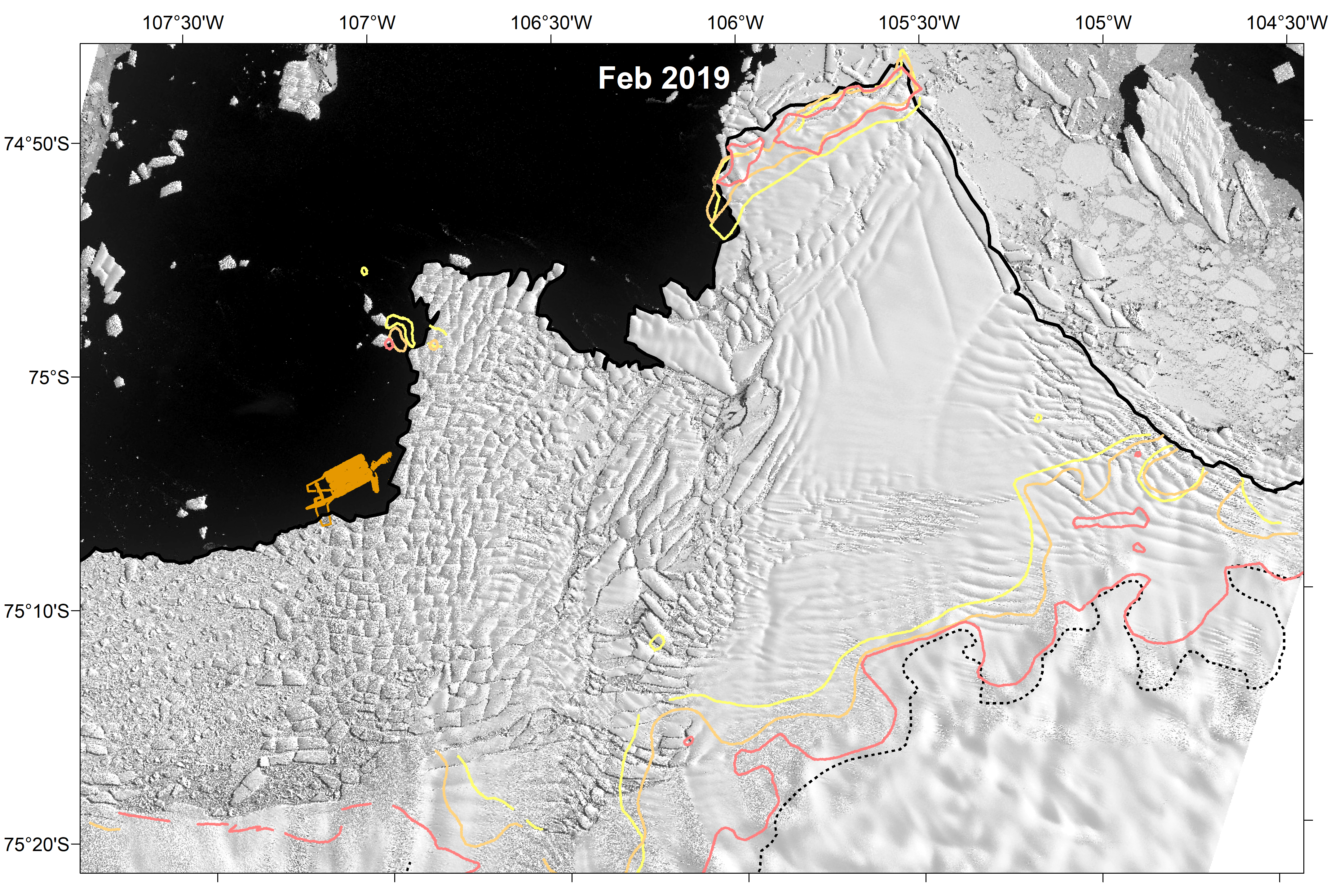

To better predict what’s to come for the glacier, and how soon its demise could occur, researchers took a closer look at the grounding zone, where the glacier’s ice transitions from its crutch on the sea floor to being a floating shelf. This “critical area” in front of the glacier provided historical data about the glacier’s past rates of retreat, and according to the University of South Florida, whose marine geophysicist Alastair Graham led the study, it “provides a kind of crystal ball” into Thwaites’ future.

The results of the study were published in Nature Geoscience on Monday.

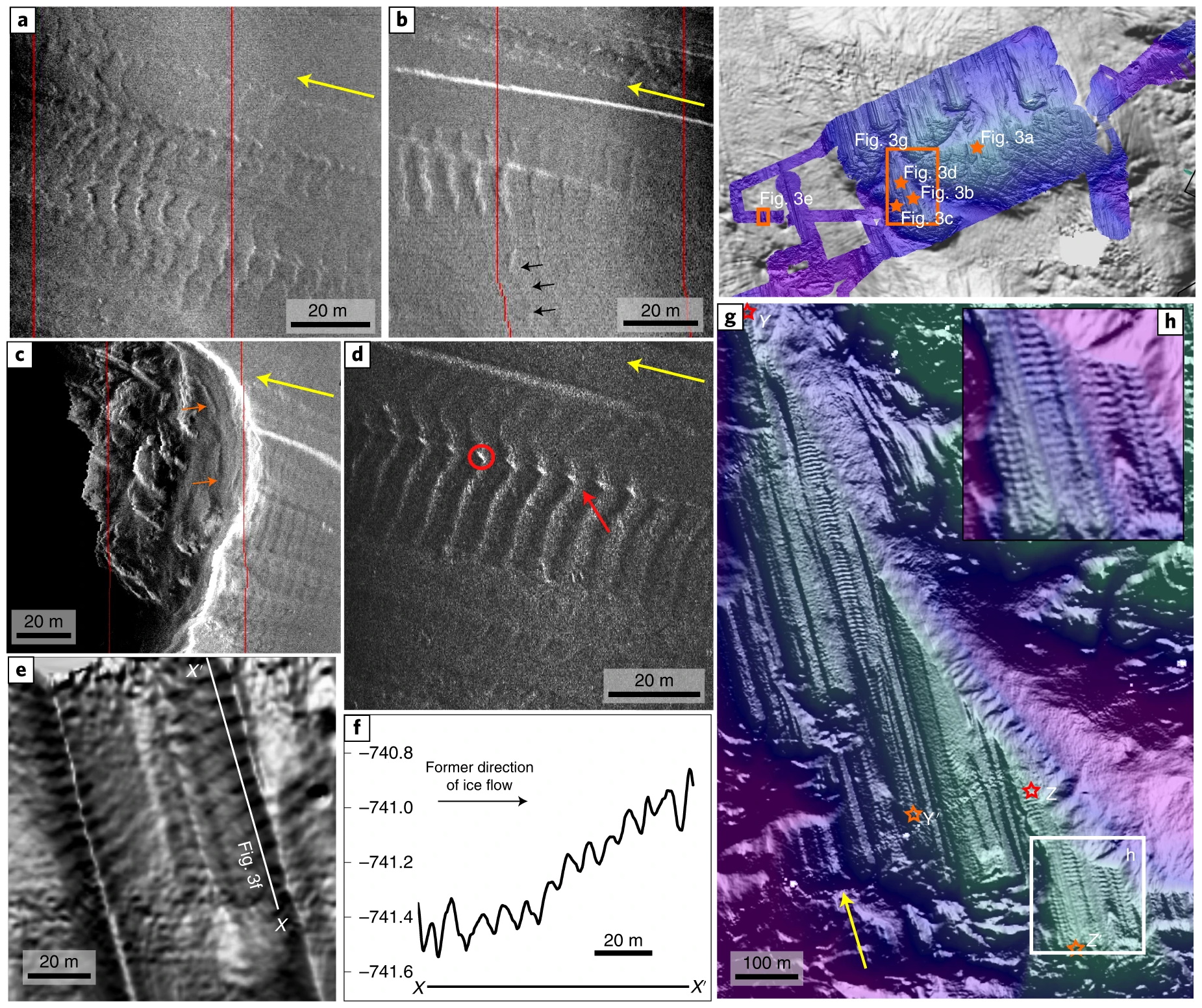

Looking at 160 parallel ridges that the glacier created as it retreated and moved along the ocean floor, scientists found that the glacier’s recently tracked rate of retreat is slower than what it’s been at times in the past. Over the course of 5.5 months at some point in the last 200 years, scientists found that the glacier retreated at a rate of more than 2.1 kilometers (1.3 miles) a year — twice the distance it retreated from 1996 to 2009 and three times the rate from 2011 to 2017.

And while that may seem like a positive signal, it’s actually a sign that things could soon accelerate. “Similar rapid retreat pulses are likely to occur in the near future,” the study says.

“Thwaites is really holding on today by its fingernails,” study co-author and British Antarctic Survey marine geophysicist Robert Larter said in a news release. “We should expect to see big changes over small timescales in the future — even from one year to the next — once the glacier retreats beyond a shallow ridge in its bed.”

“Our results suggest that pulses of very rapid retreat have occurred at Thwaites Glacier in the last two centuries, and possibly as recently as the mid-20th Century,” said lead author Alastair Graham, of the University of South Florida’s College of Marine Science.

The more the glacier thins out, the shorter amount of time it will be before another amplified melting event, the study says, and recent observations of the glacier increase the probability that such an event could occur “in coming decades.”

Not even a year ago, scientists warned that Thwaites’ last ice shelf — the only brace that remains to prevent it from total collapse — may only last a few more years. Warm water seeping underneath the giant block of ice is a major contributor to its melting, and could help lead to the shelf’s final collapse within as little as five years.

Warm water was first discovered beneath the glacier at its grounding zone in 2020. The year before, researchers also discovered a massive cavity nearly the size of Manhattan under the glacier.

“Just a small kick to Thwaites could lead to a big response,” Graham said.

Rapid retreat of Thwaites Glacier in the pre-satellite era

ABSTRACT: Understanding the recent history of Thwaites Glacier, and the processes controlling its ongoing retreat, is key to projecting Antarctic contributions to future sea-level rise. Of particular concern is how the glacier grounding zone might evolve over coming decades where it is stabilized by sea-floor bathymetric highs. Here we use geophysical data from an autonomous underwater vehicle deployed at the Thwaites Glacier ice front, to document the ocean-floor imprint of past retreat from a sea-bed promontory. We show patterns of back-stepping sedimentary ridges formed daily by a mechanism of tidal lifting and settling at the grounding line at a time when Thwaites Glacier was more advanced than it is today. Over a duration of 5.5 months, Thwaites grounding zone retreated at a rate of >2.1 km per year—twice the rate observed by satellite at the fastest retreating part of the grounding zone between 2011 and 2019. Our results suggest that sustained pulses of rapid retreat have occurred at Thwaites Glacier in the past two centuries. Similar rapid retreat pulses are likely to occur in the near future when the grounding zone migrates back off stabilizing high points on the sea floor.