Pakistan and India suffer extreme spring heatwaves – “We are living in hell”

By Hannah Ellis-Petersen and Shah Meer Baloch

2 May 2022

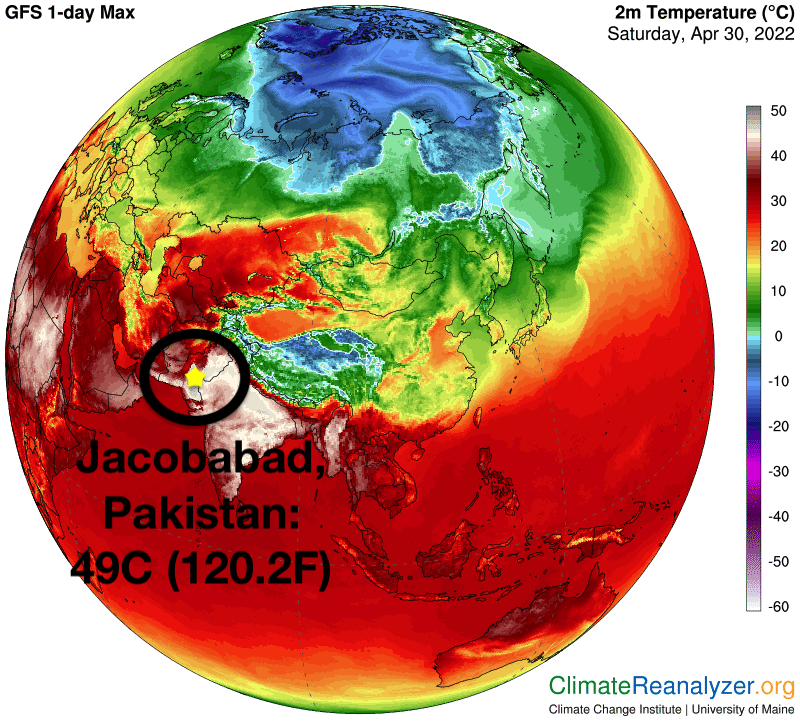

DELHI and ISLAMABAD (The Guardian) – For the past few weeks, Nazeer Ahmed has been living in one of the hottest places on Earth. As a brutal heatwave has swept across India and Pakistan, his home in Turbat, in Pakistan’s Balochistan region, has been suffering through weeks of temperatures that have repeatedly hit almost 50C (122F), unprecedented for this time of year. Locals have been driven into their homes, unable to work except during the cooler night hours, and are facing critical shortages of water and power.

Ahmed fears that things are only about to get worse. It was here, in 2021, that the world’s highest temperature for May was recorded, a staggering 54C. This year, he said, feels even hotter. “Last week was insanely hot in Turbat. It did not feel like April,” he said.

As the heatwave has exacerbated massive energy shortages across India and Pakistan, Turbat, a city of about 200,000 residents, now barely receives any electricity, with up to nine hours of load shedding every day, meaning that air conditioners and refrigerators cannot function. “We are living in hell,” said Ahmed.

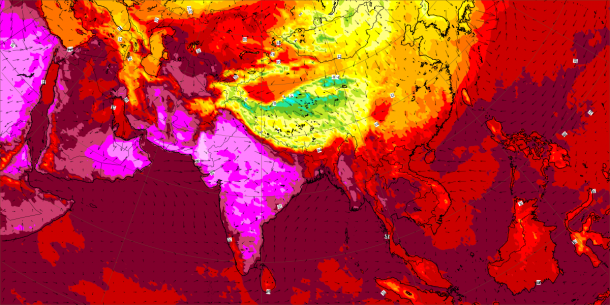

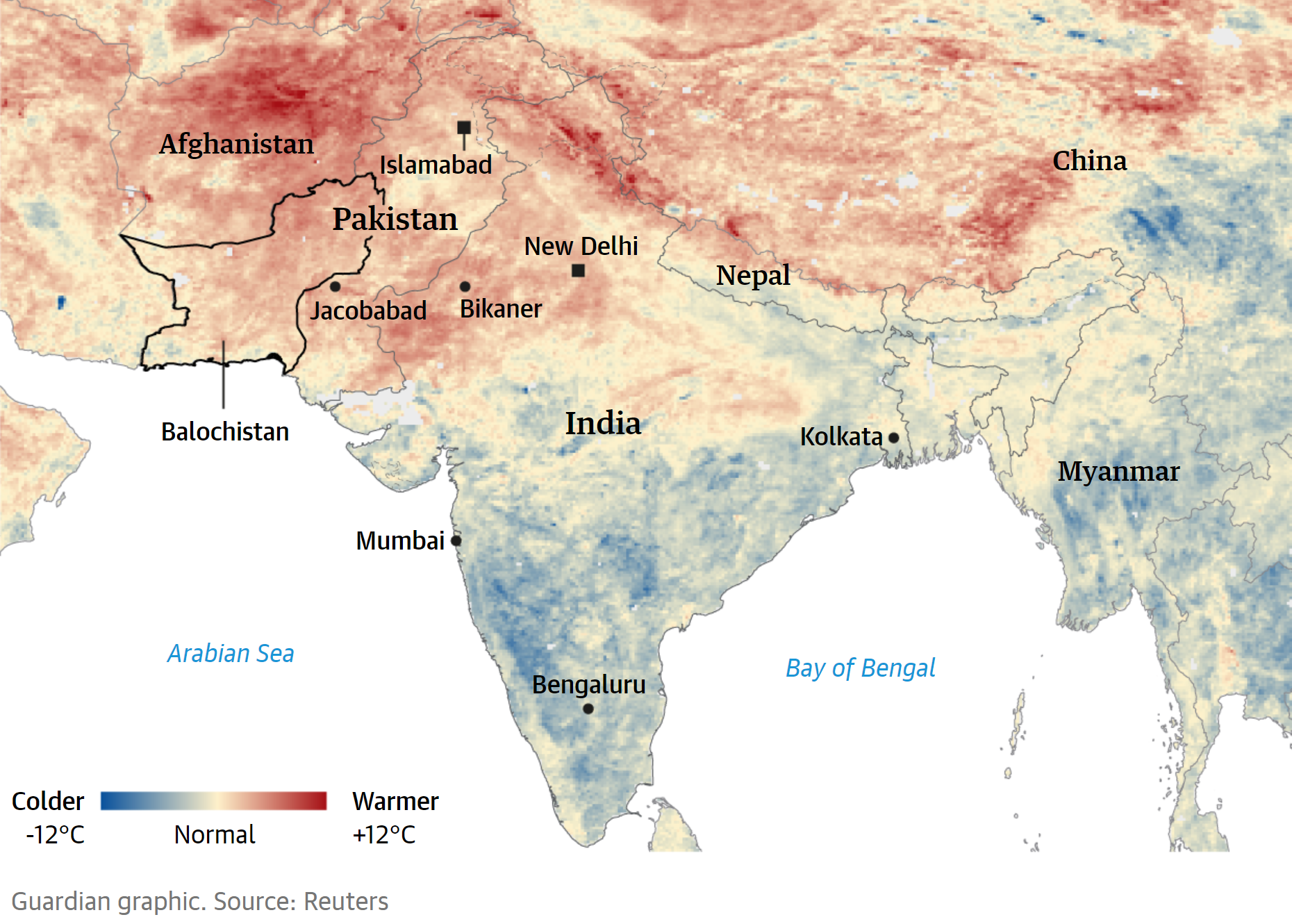

It has been a similar story across the subcontinent, where the realities of climate change are being felt by more than 1.5 billion people as the scorching summer temperatures have arrived two months early and the relief of the monsoons are months away. North-west and central India experienced the hottest April in 122 years, while Jacobabad, a city in Pakistan’s Sindh province, hit 49C on Saturday, one of the highest April temperatures ever recorded in the world.

The heatwave has already had a devastating impact on crops, including wheat and various fruits and vegetables. In India, the yield from wheat crops has dropped by up to 50% in some of the areas worst hit by the extreme temperatures, worsening fears of global shortages following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has already had a devastating impact on supplies.

In Balochistan’s Mastung district, known for its apple and peach orchards, the harvests have been decimated. Haji Ghulam Sarwar Shahwani, a farmer, watched in anguish as his apple trees blossomed more than a month early, and then despair as the blossom sizzled and then died in the unseasonal dry heat, almost killing off his entire crop. Farmers in the area also spoke of a “drastic” impact on their wheat crops, while the area has also recently been subjected to 18-hour power cuts.

“This is the first time the weather has wreaked such havoc on our crops in this area,” Shahwani said. “We don’t know what to do and there is no government help. The cultivation has decreased; now very few fruits grow. Farmers have lost billions because of this weather. We are suffering and we can’t afford it.”

Sherry Rehman, Pakistan’s minister for climate, told the Guardian that the country was facing an “existential crisis” as climate emergencies were being felt from the north to south of the country.

Rehman warned that the heatwave was causing the glaciers in the north of the country to melt at an unprecedented rate, and that thousands were at risk of being caught in flood bursts. She also said that the sizzling temperatures were not only impacting crops but water supply as well. “The water reservoirs dry up. Our big dams are at dead level right now, and sources of water are scarce,” she said.

Rehman said the heatwave should be a wake-up call to the international community. “Climate and weather events are here to stay and will in fact only accelerate in their scale and intensity if global leaders don’t act now,” she said.

Experts said the scorching heat being felt across the subcontinent was likely a taste of things to come as global heating continues to accelerate. Abhiyant Tiwari, an assistant professorand programme manager at the Gujarat Institute of Disaster Management, said “the extreme, frequent, and long-lasting spells of heatwaves are no more a future risk. It is already here and is unavoidable.”

The World Meteorological Organisation said in a statement that the temperatures in India and Pakistan were “consistent with what we expect in a changing climate. Heatwaves are more frequent and more intense and starting earlier than in the past.” [more]

‘We are living in hell’: Pakistan and India suffer extreme spring heatwaves

India and Pakistan act to save lives from extreme heat

29 April 2022 (WMO) – Extreme heat is gripping large parts of India and Pakistan, impacting hundreds of millions of people in one of the most densely populated parts of the world. The national meteorological and hydrological departments in both countries are working closely with health and disaster management agencies to roll out heat health action plans which have been successful in saving lives in the past few years.

The India Meteorological Department said that maximum temperatures reached 43-46°C in widespread areas on 28 April and that this intense heat will continue until 2 May.

Similar temperatures have been seen in Pakistan. The Pakistan Meteorological Department said that daytime temperatures are likely to be between 5°C and 8°C above normal in large swathes of the country.

It warned that in the mountainous regions of Gilgit-Baltistan and Khyber Pakhtunkwa, the unusual heat would enhance the melting of snow and ice and might trigger glacial lake outburst floods or flash floods in vulnerable areas.

Air quality has deteriorated, and large swathes of land are at risk of extreme fire danger.

“Heatwaves have multiple and cascading impacts not just on human health, but also on ecosystems, agriculture, water and energy supplies and key sectors of the economy. The risks to society underline why the World Meteorological Organization is committed to ensuring that multi-hazard early warning services reach the most vulnerable,” said WMO Secretary-General Prof. Petteri Taalas.

“It is premature to attribute the extreme heat in India and Pakistan solely to climate change. However, it is consistent with what we expect in a changing climate. Heatwaves are more frequent and more intense and starting earlier than in the past,” he said.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, in its Sixth Assessment Report, said that heatwaves and humid heat stress will be more intense and frequent in South Asia this century.

India’s Ministry of Earth Sciences recently issued an open-access publication about climate change in India. It devoted a whole chapter to temperature change.

- The frequency of warm extremes over India has increased during 1951–2015, with accelerated warming trends during the recent 30 year period 1986–2015 (high confidence). Significant warming is observed for the warmest day, warmest night and coldest night since 1986.

- The pre-monsoon season heatwave frequency, duration, intensity and areal coverage over India are projected to substantially increase during the twenty-first century (high confidence).

The heatwave was triggered by a high pressure system and follows an extended period of above average temperatures.

India recorded its warmest March on record, with an average maximum temperature of 33.1 ºC, or 1.86 °C above the long-term average. Pakistan also recorded its warmest March for at least the past 60 years, with a number of stations breaking March records.

In the pre-monsoon period, both India and Pakistan regularly experience excessively high temperatures, especially in May. Heatwaves do occur in April but are less common. It is too soon to know whether new national temperature records will be set. Turbat, in Pakistan, recorded the world’s fourth highest temperature of 53.7°C on 28 May 2017. [more]