Australia’s cataclysmic floods raise specter of permanent retreat as towns become uninsurable – Sydney to be hit by another 100mm (4 inches) of rain in four days as bureau warns of flood fatigue – “The taxpayer is now the insurer”

By Sarah Keoghan and Laura Chung

22 March 2022

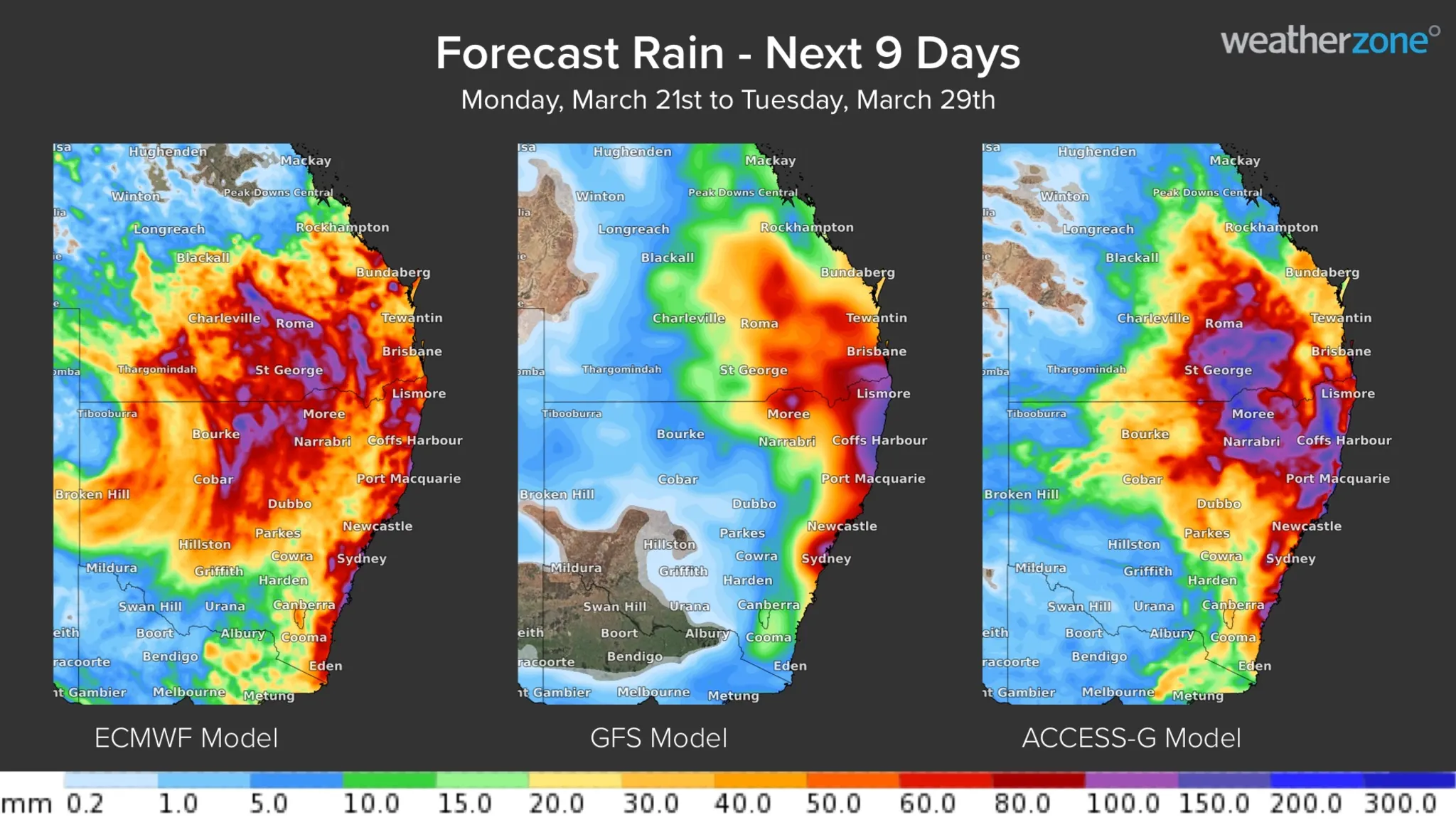

(SMH) – The Bureau of Meteorology has urged residents in flood-prone areas to remain vigilant as 100 millimetres of rain is forecast for Sydney over the next four days.

Senior meteorologist Jackson Browne said the weather bureau was concerned flood-fatigued residents living in at-risk areas may be less inclined to stay up to date with weather warnings.

Mr Browne said an estimated 100mm is set to fall along the NSW coast, including Sydney, from late Wednesday in a weather event that could lead to flash flooding.

More than 150mm of rain is predicted over the seven days until next Wednesday, he said.

“Everyone is acutely aware of the floods over the past couple of weeks, but we are really encouraging people not to be fatigued with it,” he said.

“Stay across the messaging, as we know La Nina will be around for at least another month.”

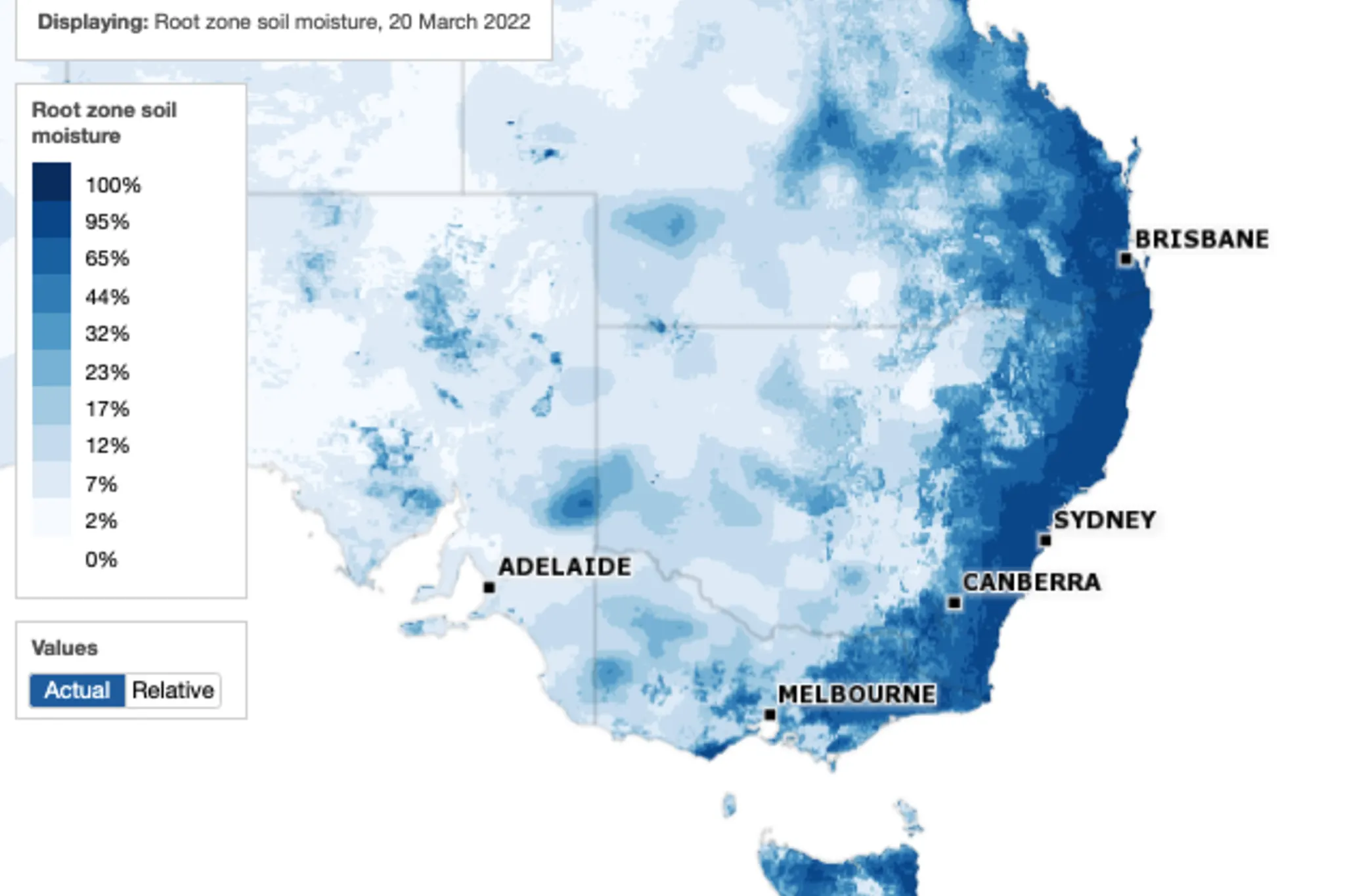

Mr Browne said rivers and water catchments across the state’s east coast have not had enough time to dry out since the flood emergency at the start of the month, and therefore are at greater flood risk, even with a small amount of rain.

“It’s not welcome news. We don’t need heavy rains to [cause flash flooding],” he said. [more]

Sydney to be hit by 100mm of rain in four days as bureau warns of flood fatigue

Australia’s cataclysmic floods raise spectre of communities’ permanent retreat

By James Fernyhough

20 March 2022

LISMORE, Australia (Financial Times) – Brett Girard was in his lakeside caravan when freakishly heavy rain began falling on the Australian town of Lismore.

The 54-year-old’s instinct was to flee, but he and his friends were told to wait for help. Hours later water was filling up his caravan, and emergency services said it was now too dangerous to attempt a rescue. So he spent the most terrifying night of his life clinging to a pole on the side of a building at the caravan park, floodwaters swirling round his neck.

“The water come like you wouldn’t believe,” he said. “I was kicking cows off my pole [that were] trying to get over me and on to the roof. There were cows drowning everywhere.”

Now homeless and staying at an evacuation centre nearby, Girard felt he was “left for dead” by authorities who were unprepared for a disaster that experts said was entirely predictable. The “rain bomb” that hit Lismore in New South Wales on February 28 was unprecedented. As much as 700mm of rain fell in 24 hours — more than London typically receives in a year. It caused the nearby Wilson river to rise 14.4 metres above its normal level, covering most of the town centre with water. Four people died.

A few weeks later, Lismore resembles a war zone. Piles of rubble and detritus line the streets. Army trucks patrol the area, bringing supplies and helping with the clean-up effort. Every shopfront reveals the same devastation: windows smashed, ceilings caved in and nothing salvageable.

Megan Cusack, a barrister whose chambers were filled almost to the ceiling with water, said she did not have contents insurance.

“You can’t get insurance for floods here, unless you want to spend A$20,000 [US14,500] a year.” She estimated the damage at A$100,000.

Robin Gilmore, who owns the Civic Hotel, where floodwaters reached the second floor, estimated his losses at A$2.5mn. Local resident Max, 74, who had to be rescued from his front porch in waist-deep water, said he would have to raid his pension to pay for the damage. Neither had insurance.

Lismore is just one of countless communities, from Brisbane to Sydney, hit by extreme rainfall and flash flooding in late February and early March. The Insurance Council of Australia put the total claims at A$2.2bn and counting. That takes no account of the huge uninsured losses. […]

Geoff Summerhayes, former chief insurance regulator and now a senior adviser at climate change advisory Pollination, said: “We’re taking a backward view to catastrophes, but we know that with climate change the past is no longer a predictor of the future.” […]

Insurers have withdrawn from much of northern Australia, which is particularly vulnerable to cyclones, prompting the government last year to introduce its own A$10bn cyclone reinsurance pool. Similar government pools exist in the UK, US and Japan. “But all that means is the taxpayer is now the insurer,” Summerhayes said. [more]

Australia’s cataclysmic floods raise spectre of communities’ permanent retreat

Australia: After the bushfires came the floods

17 March 2022 (UNEP) – In the past three weeks, tens of thousands of Australians have had to evacuate their homes after devastating floods struck the eastern part of the country.

Some regions experienced their worst flooding in decades, as torrential rain submerged residential areas, cut power lines and caused reservoirs to swell past the bursting point, resulting in tens of millions of dollars in damage.

New South Wales Premier Dominic Perrottet called the floods a “once-in-a-thousand-year event.”

But experts say climate change is fuelling an increase in extreme weather across Australia, threatening to make bushfires, floods and droughts more common.

A report published last month by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and GRID Arendal predicts that wildfires will become more frequent and intense, with a global increase of extreme fires by 50 per cent by the end of the century. The increase in wildfires renders land barren, which leads to increased run-off and, therefore, floods and, later, drought.

It’s a trend that is happening around the world, says Alvin Chandra, an expert in climate change adaptation with UNEP. And many countries, he warns, are not prepared.

We spoke with Chandra about the flooding in Australia and what states need to do to ready themselves for the new ‘climate normal’.

Globally, the number of flood-related catastrophes has more than doubled since 2000. Is Australia seeing a spike in flooding as well?

Alvin Chandra (AC): Scientists are united in the view that extreme flooding is becoming more prevalent in Australia, which can be attributed to warmer oceans that increase the amount of moisture moving from the sea to the atmosphere. This will most likely increase the intensity of extreme rainfall, extreme bushfires, and extreme heatwaves.

The recent floods in Australia are some of the worst the country has ever experienced and have caused widespread devastation. To give just one example, Brisbane has experienced 80 per cent of its annual rainfall in just three days. These are the same communities where we saw massive bushfires in 2019 and 2020 which resulted in the loss of shrubs and trees setting the scene for extreme flooding.

Many people view climate change as a future problem. But has Australia’s climate already shifted?

AC: Australia – along with the Pacific Islands and Southeast Asia region – is in one of the most vulnerable regions [in the world to climate change]. Many of the communities dealing with this recent flooding have already had to deal with a range of cascading climate events in recent years. These droughts, bushfires, powerful storms and heat waves amplify the scientific evidence predicted by IPCC reports that we are already living in a changed climate.

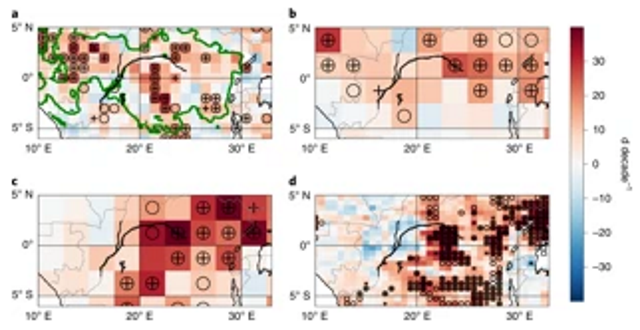

UNEP: Beyond Australia, what parts of the world will be the hardest hit by extreme weather?

AC: Almost all parts of the world are experiencing a changed climate. When you [factor] in the human dimension of vulnerability, there are global hotspots in places such as West, Central and East Africa, South Asia, and Central and South America, small island developing states and the Arctic. Here we find that vulnerability is higher as [local populations] live in poverty. They have limited access to basic resources and there are often incidences of violent conflict.

There are also high levels of reliance on climate-sensitive livelihoods: many [people in these places] are small-holder farmers, pastoralists or live in fishing communities. In the past decade, human mortality from floods, droughts and storms was 15 times higher in these vulnerable regions compared to regions with lower vulnerabilities. Vulnerability is also a factor of a government’s institutional and financial ability to respond. These communities are often at the receiving end of capacity gaps at multiple levels.

How many people globally are affected by extreme weather?

AC: Evidence suggests that some 85 per cent of the global population has already experienced extreme weather events. The recent IPCC report suggests that lives of at least 1 billion people could be made worse by climate change by 2050, where the vulnerable communities expect to suffer the worst impacts. [more]

Australia: After the bushfires came the floods

Deadly climate change-fueled floods inundate Australia’s east coast

By Andrew Freedman

7 March 2022

(Axios) – For more than two weeks, Australia’s east coast has been inundated by a series of rainstorms so severe they’ve earned a foreboding moniker fit for today’s supercharged weather, “rain bombs.”

Threat level: So far, at least 22 people have perished in the floods, and tens of thousands have been forced to evacuate their homes.

Driving the news: Scenes of flash flooding turning city streets and country streams into raging rivers have played out from Queensland, including Australia’s third-largest city of Brisbane, south to New South Wales, including Sydney.

- The floods have been so severe they prompted Prime Minister Scott Morrison to declare a national emergency.

The big picture: Australia is perhaps the best example of a region that is now, thanks to a combination of natural factors and human-caused climate change, alternating between heat, drought and wildfires on the one hand, and heavy rains with flooding on the other.

- It’s exhibit A for the Anthropocene.

- “New South Wales was hit hard by the 2019-20 Black Summer bushfires, and now it is in the grips of another climate-driven disaster. The recovery time for communities and emergency services between events is shrinking,” Simon Bradshaw, a researcher at the Australian Climate Council, told Axios via email. […]

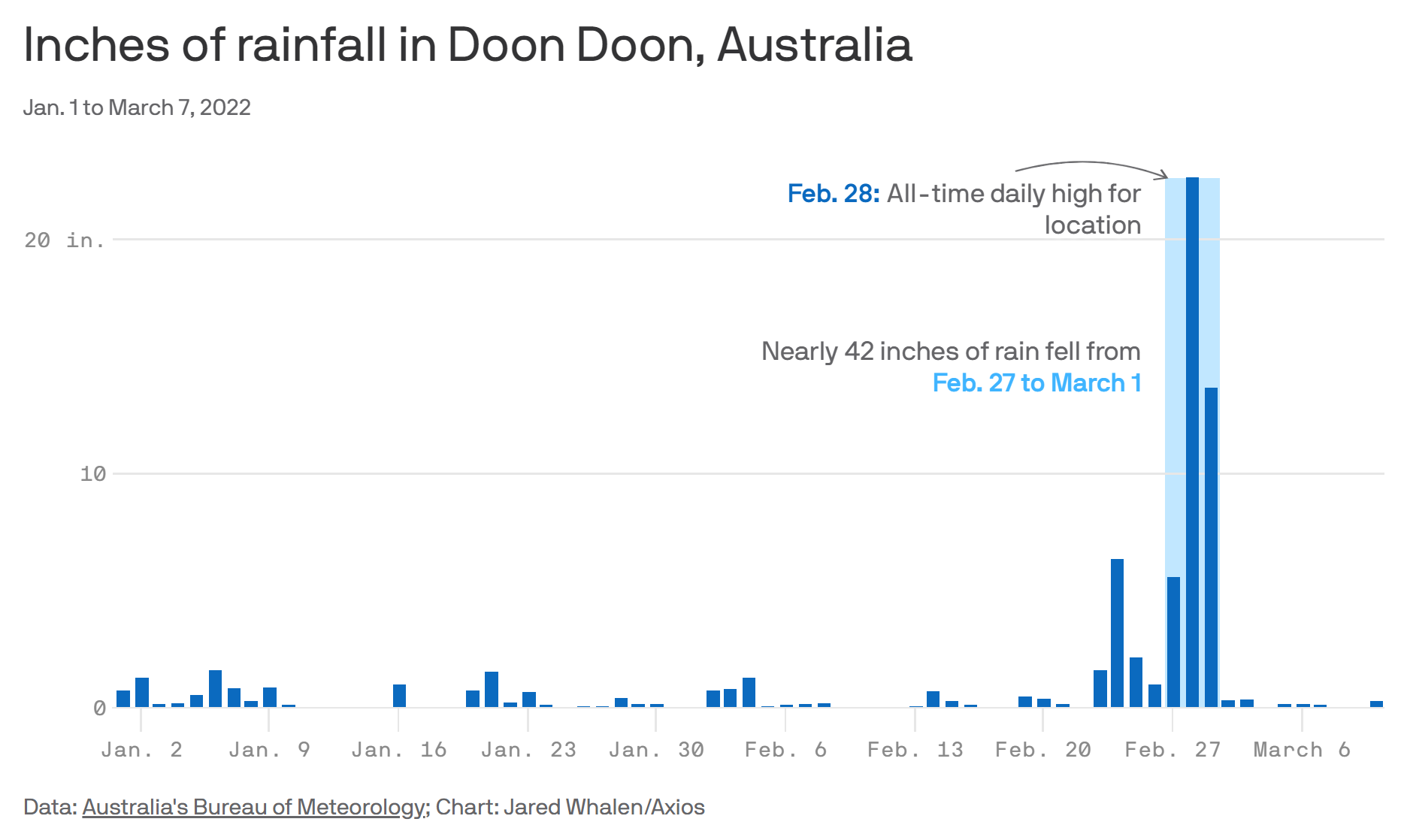

By the numbers: The rainfall amounts in Australia have been off the charts.

- The town of Doon Doon, New South Wales, received 1 meter of rainfall in 48 hours, for a total of about 42 inches. That’s the same as the annual average precipitation in Washington, D.C.

- Brisbane had three days, Feb. 26-28, with more than 7.9 inches each day, for a record three-day total of 26.6 inches.

- Flood levels in the town of Lismore in northern New South Wales reached 47.1 feet, about 6.6 feet higher than the previous record. [more]

Deadly climate change-fueled floods inundate Australia’s east coast

Will this help reduce emissions?

https://mikethompson.house.gov/newsroom/press-releases/thompson-larson-underwood-introduce-bill-to-provide-energy-rebate-to