Why is U.S. productivity so weak? Three theories

[cf. U.K. parliamentary group warns that global fossil fuels could peak in less than 10 years] By Neil Irwin

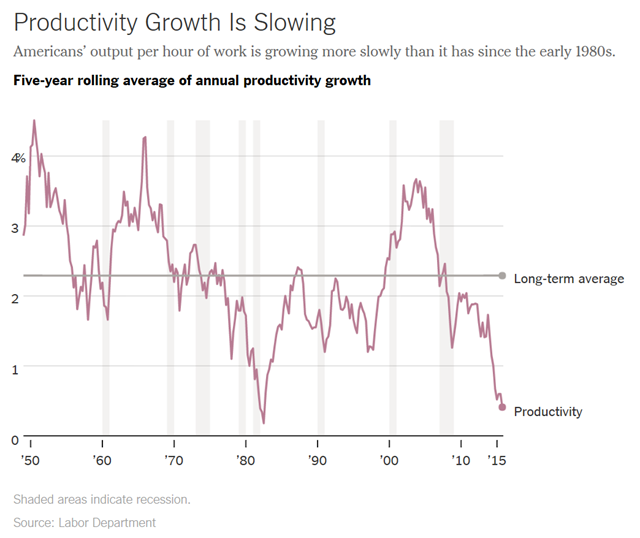

28 April 2016 (The New York Times) – More than 151 million Americans count themselves employed, a number that has risen sharply in the last few years. The question is this: What are they doing all day? Because whatever it is, it barely seems to be registering in economic output. The number of hours Americans worked rose 1.9 percent in the year ended in March. New data released Thursday showed that gross domestic product in the first quarter was up 1.9 percent over the previous year. Despite constant advances in software, equipment and management practices to try to make corporate America more efficient, actual economic output is merely moving in lock step with the number of hours people put in, rather than rising as it has throughout modern history. We could chalk that up to a statistical blip if it were a single year; productivity data are notoriously volatile. But this has been going on for some time. From 2011 through 2015, the government’s official labor productivity measure shows only 0.4 percent annual growth in output per hour of work. That’s the lowest for a five-year span since the 1977-to-1982 period, and far below the 2.3 percent average since the 1950s.

Productivity is one of the most important yet least understood areas of economics. Over long periods, it is the only pathway toward higher levels of prosperity; the reason an American worker makes much more today than a century ago is that each hour of labor produces much more in goods and services. Put bluntly, if the kind of productivity growth implied by the new data published Thursday were to persist indefinitely, your grandchildren would be no richer than you. But it is also really hard to measure, particularly for service firms. (How productive were employees at Facebook, or your local bank, last quarter? Have fun trying to figure it out.) And even with years of hindsight, economists are never quite sure why productivity rises or falls. During the 2008 recession, labor productivity soared. Was this because employers laid off their least productive workers first? Because everybody worked harder, fearful for their jobs? Or was it a measurement problem as government statistics-takers struggled to capture fast-moving changes in the economy? We don’t know for sure. (Here’s one analysis that emphasizes the first explanation.) [more]