U.S. Federal Reserve official: Global warming is an international market failure – “Climate-based risk could threaten the stability of the financial system as a whole”

By Eric Holthaus

26 March 2019

(Grist) – Climate change was already worrying enough — now a report from the U.S. central bank cautions that rising temperatures and extreme storms could eventually trigger a financial collapse.

A Federal Reserve researcher warned in a report on Monday that “climate-based risk could threaten the stability of the financial system as a whole.” But possible fixes — using the Fed’s buying power to green the economy — are currently against the law.

Glenn Rudebusch, the San Francisco Fed’s executive vice president for research, ranks climate change as one of the three “key forces transforming the economy,” along with an aging population and rapid advances in technology. Climate change could soon hit the banking system “by storms, droughts, wildfires, and other extreme events” making it harder for businesses to repay loans.

Rudebusch warns that crops and inundated cities have already started to hurt the economy: “Economists view these losses as the result of a fundamental market failure: carbon fuel prices do not properly account for climate change costs,” he writes. “Businesses and households that produce greenhouse gas emissions, say, by driving cars or generating electricity, do not pay for the losses and damage caused by that pollution.”

A hefty carbon tax alone wouldn’t be enough to fix the problem — what he calls an “intergenerational and international market failure.” [more]

Fed official: Climate change is an ‘international market failure’

Climate change and the Federal Reserve

By Glenn D. Rudebusch

25 March 2019

(FRBSF) – To help foster macroeconomic and financial stability, it is essential for Federal Reserve policymakers to understand how the economy operates and evolves over time. In this century, three key forces are transforming the economy: a demographic shift toward an older population, rapid advances in technology, and climate change. Climate change has direct effects on the economy resulting from various environmental shifts, including hotter temperatures, rising sea levels, and more frequent and extreme storms, floods, and droughts. It also has indirect effects resulting from attempts to adapt to these new conditions and from efforts to limit or mitigate climate change through a transition to a low-carbon economy. This Economic Letter describes how the consequences of climate change are relevant for the Fed’s monetary and financial policy.

Climate change and the transition to a low-carbon economy

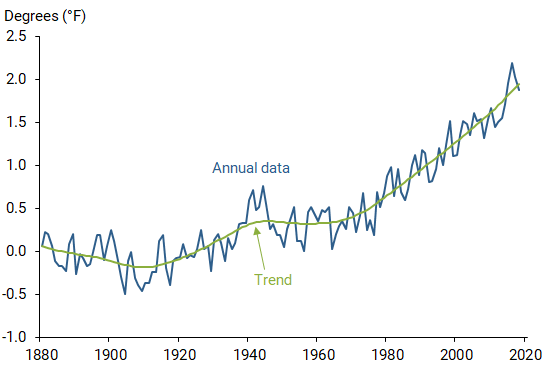

Surface temperatures were first regularly recorded around the world in the late 1800s. Since then, the global average temperature has risen almost 2°F (Figure 1) with further increases projected (IPCC 2018). Based on extensive scientific theory and evidence, a consensus view among scientists is that global warming is the result of carbon emissions from burning coal, oil, and other fossil fuels. Indeed, as early as 1896, the Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius showed that carbon emissions from human activities could cause global warming through a greenhouse effect. The underlying science is straightforward: Certain gases in the atmosphere, such as carbon dioxide and methane, capture the sun’s heat that is reflected off the Earth’s surface, thus blocking that heat from escaping into space. These greenhouse gases act like a blanket around the earth holding in heat. As more fossil fuels are burned, the blanket gets thicker, and global average temperatures increase. Other empirical measurements have confirmed many related adverse environmental changes such as rising sea levels and ocean acidity, shrinking glaciers and ice sheets, disappearing species, and more extreme storms (USGCRP 2018).

Climate change also affects the U.S. economy. The latest National Climate Assessment, a 1,515-page scientific report produced by 13 federal agencies as required by law, summarized this impact:

Without substantial and sustained global mitigation and regional adaptation efforts, climate change is expected to cause growing losses to American infrastructure and property and impede the rate of economic growth over this century.

National Climate Assessment, USGCRP 2018, pp. 25–26

Economists view these losses as the result of a fundamental market failure: carbon fuel prices do not properly account for climate change costs. Businesses and households that produce greenhouse gas emissions, say, by driving cars or generating electricity, do not pay for the losses and damage caused by that pollution. Therefore, they have no direct incentive to switch to a low-carbon technology that would curtail emissions. Without proper price signals and incentives in the private market, some kind of collective or government action is necessary. One solution would be to charge for the full cost of carbon pollution through an extra fee on emissions—a carbon tax—that would account for the costs of climate change on the economy and society. Many leading economists are calling for a carbon tax to correct market pricing (Climate Leadership Council 2019, Fried, Novan, and Peterman 2019).

A carbon tax that is set at the proper level can appropriately incentivize innovations in clean technology and the transition from a high- to a low-carbon economy. Such a carbon tax should equal the “social cost of carbon,” which measures the total damage from an additional ton of carbon pollution (Auffhammer 2018). A crucial consideration in calculating this cost is that carbon pollution dissipates very slowly and will remain in the atmosphere for centuries, redirecting heat back toward the earth. Consequently, today’s carbon pollution will create climate hazards for many generations to come. A second difficulty in calculating the social cost of carbon is tail risk, namely, the possibility of catastrophic future climate damage (Heal 2017). A final complication is that the causes and consequences of climate change are global in scope. The resulting intergenerational and international market failure is so problematic that some economists doubt that a carbon tax alone would suffice (Tvinnereim and Mehling 2018). Instead, a comprehensive set of government policies may be required, including clean-energy and carbon-capture research and development incentives, energy efficiency standards, and low-carbon public investment (Gillingham and Stock 2018).

Climate change and the Fed

Given the role of government in addressing climate change, how does the Federal Reserve fit in? In particular, how does climate change relate to the Fed’s goals of financial and macroeconomic stability? With regard to financial stability, many central banks have acknowledged the importance of accounting for the increasing financial risks from climate change (Scott, van Huizen, and Jung 2017, NGFS 2018). These risks include potential loan losses at banks resulting from the business interruptions and bankruptcies caused by storms, droughts, wildfires, and other extreme events. There are also transition risks associated with the adjustment to a low-carbon economy, such as the unexpected losses in the value of assets or companies that depend on fossil fuels. In this regard, even long-term risks can have near-term consequences as investors reprice assets for a low-carbon future. Furthermore, financial firms with limited carbon emissions may still face substantial climate-based credit risk exposure, for example, through loans to affected businesses or mortgages on coastal real estate. If such exposures were broadly correlated across regions or industries, the resulting climate-based risk could threaten the stability of the financial system as a whole and be of macroprudential concern. In response, the financial supervisory authorities in a number of countries have encouraged financial institutions to disclose any climate-related financial risks and to conduct “climate stress tests” to assess their solvency across a range of future climate change alternatives (Campiglio et al. 2018).

Some central banks also recognize that climate change is becoming increasingly relevant for monetary policy (Lane 2017, Cœuré 2018). For example, climate-related financial risks could affect the economy through elevated credit spreads, greater precautionary saving, and, in the extreme, a financial crisis. There could also be direct effects in the form of larger and more frequent macroeconomic shocks associated with the infrastructure damage, agricultural losses, and commodity price spikes caused by the droughts, floods, and hurricanes amplified by climate change (Debelle 2019). Even weather disasters abroad can disrupt exports, imports, and supply chains close to home. As a much more persistent factor, Colacito et al. (2018) found that the current trend toward higher temperatures on its own has slowed growth in a variety of sectors. They estimated that increased warming has already started to reduce average U.S. output growth and that, as temperatures rise, growth may be curtailed by more than ½ percentage point later in this century.

On top of these direct effects, climate adaptation—with spending on equipment such as air conditioners and resilient infrastructure including seawalls and fortified transportation systems—is expected to increasingly divert resources from productive capital accumulation. Similarly, sizable investments would be necessary to reduce carbon pollution and mitigate climate change, and the transition to a low-carbon future may affect the economy through a variety of other channels (Batten 2018). In short, climate change is becoming relevant for a range of macroeconomic issues, including potential output growth, capital formation, productivity, and the long-run level of the real interest rate.

Nevertheless, some view the economic and financial concerns surrounding climate change as having either too short or too long a time horizon to affect monetary policy decisions. Indeed, at the short end, monetary policy typically does not react to temporary disturbances from weather events like hurricanes or blizzards. However, climate change could cause such shocks to grow in size and frequency and their disruptive effects could become more persistent and harder to ignore. At the long end, most of the consequences of climate change will occur well past the usual policy forecast horizon of a few years ahead. However, even longer-term factors can be relevant for monetary policy. For example, central banks routinely consider the policy implications of demographic trends, such as declining labor force participation, which have long-run effects much like climate change. In addition, prices of equities and long-term financial assets depend on expected future conditions, so even climate risks decades ahead can have near-term financial consequences. Climate change could also be a factor in achieving and maintaining low inflation. It took a decade or two—a relevant time scale for climate change—for the Fed to achieve its inflation objective after the Great Inflation of the 1970s and the Great Recession. Finally, the economic research that quantifies optimal monetary policy routinely uses a very long-run perspective that takes into account inflation and output quite far out in the future.

While the effects and risks of climate change are relevant factors for the Fed to consider, the Fed is not in a position to use monetary policy actively to foster a transition to a low-carbon economy. Supporting environmental sustainability and limiting climate change are not directly included in the Fed’s statutory mandate of price stability and full employment. Furthermore, the Fed’s short-term interest rate policy tool is not amenable to supporting low-carbon industries. Wind farms in Kansas and coal mines in West Virginia face the same underlying risk-free short-term interest rate. Instead, some have advocated that central banks use their balance sheet to support the transition to a low-carbon economy, for example, by buying low-carbon corporate bonds (Olovsson 2018). Such “green” quantitative easing is an option for some central banks but not for the Fed, which by law can only purchase government or government agency debt.

Conclusion

Many central banks already include climate change in their assessments of future economic and financial risks when setting monetary and financial supervisory policy. For the Fed, the volatility induced by climate change and the efforts to adapt to new conditions and to limit or mitigate climate change are also increasingly relevant considerations. Moreover, economists, including those at central banks, can contribute much more to the research on climate change hazards and the appropriate response of central banks.

Glenn D. Rudebusch is senior policy advisor and executive vice president in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

“Businesses and households that produce greenhouse gas emissions, say, by driving cars or generating electricity, do not pay for the losses and damage caused by that pollution.” Isn’t the government one of the biggest polluters?

https://www.counterpunch.org/2015/07/23/72279/