Sharp rise in methane levels threatens world climate targets – “What we are now witnessing is extremely worrying”

By Robin McKie

17 February 2019

(The Guardian) – Dramatic rises in atmospheric methane are threatening to derail plans to hold global temperature rises to 2C, scientists have warned.

In a paper published this month by the American Geophysical Union, researchers say sharp rises in levels of methane – which is a powerful greenhouse gas – have strengthened over the past four years. Urgent action is now required to halt further increases in methane in the atmosphere, to avoid triggering enhanced global warming and temperature rises well beyond 2C.

“What we are now witnessing is extremely worrying,” said one of the paper’s lead authors, Professor Euan Nisbet of Royal Holloway, University of London. “It is particularly alarming because we are still not sure why atmospheric methane levels are rising across the planet.”

Methane is produced by cattle, and also comes from decaying vegetation, fires, coal mines and natural gas plants. It is many times more potent as a cause of atmospheric warming than carbon dioxide (CO2). However, it breaks down much more quickly than CO2 and is found at much lower levels in the atmosphere.

During much of the 20th century, levels of methane, mostly from fossil fuel sources, increased in the atmosphere but, by the beginning of the 21st century, it had stabilised, said Nisbet. “Then, to our surprise, levels starting rising in 2007. That increase began to accelerate after 2014 and fast growth has continued.”

Studies suggest these increases are more likely to be mainly biological in origin. However, the exact cause remains unclear. Some researchers believe the spread of intense farming in Africa may be involved, in particular in tropical regions where conditions are becoming warmer and wetter because of climate change. Rising numbers of cattle – as well as wetter and warmer swamps – are producing more and more methane, it is argued.

This idea is now being studied in detail by a consortium led by Nisbet, whose work is funded by the Natural Environment Research Council. This month the consortium completed a series of flights over Uganda and Zambia to collect samples of the air above these countries.

“We have only just started analysing our data but have already found evidence that a great plume of methane now rises above the wetland swamps of Lake Bangweul in Zambia,” added Nisbet.

However, other scientists warn that there could be a more sinister factor at work. Natural chemicals in the atmosphere – which help to break down methane – may be changing because of temperature rises, causing it to lose its ability to deal with the gas.

Our world could therefore be losing its power to cleanse pollutants because it is heating up, a climate feedback in which warming allows more greenhouse gases to linger in the atmosphere and so trigger even more warming. [more]

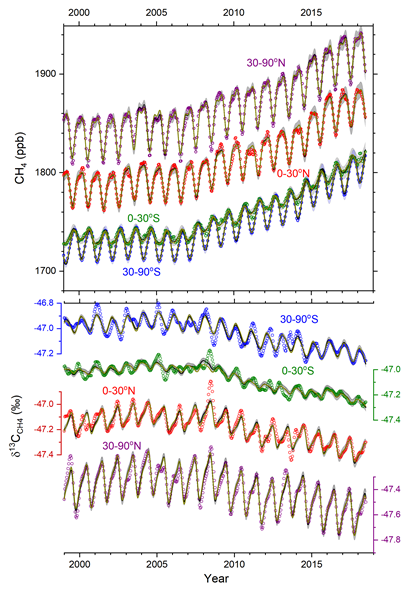

Sharp rise in methane levels threatens world climate targets

ABSTRACT: Atmospheric methane grew very rapidly in 2014 (12.7±0.5 ppb/yr), 2015 (10.1±0.7 ppb/yr), 2016 (7.0± 0.7 ppb/yr) and 2017 (7.7±0.7 ppb/yr), at rates not observed since the 1980s. The increase in the methane burden began in 2007, with the mean global mole fraction in remote surface background air rising from about 1775 ppb in 2006 to 1850 ppb in 2017. Simultaneously the 13C/12C isotopic ratio (expressed as δ13CCH4) has shifted, in a new trend to more negative values that have been observed worldwide for over a decade. The causes of methane’s recent mole fraction increase are therefore either a change in the relative proportions (and totals) of emissions from biogenic and thermogenic and pyrogenic sources, especially in the tropics and sub‐tropics, or a decline in the atmospheric sink of methane, or both. Unfortunately, with limited measurement data sets, it is not currently possible to be more definitive. The climate warming impact of the observed methane increase over the past decade, if continued at >5 ppb/yr in the coming decades, is sufficient to challenge the Paris Agreement, which requires sharp cuts in the atmospheric methane burden. However, anthropogenic methane emissions are relatively very large and thus offer attractive targets for rapid reduction, which are essential if the Paris Agreement aims are to be attained.

SIGNIFICANCE: The rise in atmospheric methane (CH4), which began in 2007, accelerated in the past four years. The growth has been worldwide, especially in the tropics and northern mid‐latitudes. With the rise has come a shift in the carbon isotope ratio of the methane. The causes of the rise are not fully understood, and may include increased emissions and perhaps a decline in the destruction of methane in the air. Methane’s increase since 2007 was not expected in future greenhouse gas scenarios compliant with the targets of the Paris Agreement, and if the increase continues at the same rates it may become very difficult to meet the Paris goals. There is now urgent need to reduce methane emissions, especially from the fossil fuel industry.