Mexico City’s water “Day Zero” may come even for the wealthiest residents – “No one could have foreseen this would happen in the city”

By Kasha Patel

25 May 2024

MEXICO CITY (The Washington Post) – Raquel Campos’ water issues started in January, when her condo building’s manager sent residents a message saying that the city hadn’t delivered water to its cistern. Four days later, taps in the upscale residence went dry.

Campos has lived in the wealthy Polanco neighborhood for 18 years and said she has never experienced water issues like this. Her husband paid to shower at a nearby hotel and she called water delivery companies that were overwhelmed with a sudden deluge of requests from the neighborhood. The water in Campos’ building came back within a few days, but with much lower pressure. Water is now delivered about every two weeks. Each unit has paid to cover the cost, increasing their monthly condo expenses by 30 percent.

Water scarcity has long been an issue in Mexico City, with the brunt of the shortages happening in lower-income neighborhoods on the outskirts of the city center. But recently, residents in some of the city’s wealthier neighborhoods have also been running out of water as hot temperatures, low rainfall and poor infrastructure have converged to create a crisis across the sprawling metropolis.

Mexico City gets about a quarter of its water from the Cutzamala system, a series of reservoirs, water treatment plants and lengthy canals and tunnels, which is running dry. Some say the system could be unable to provide water by June 26, known as “Day Zero” in the metropolitan area of 22 million, although scientists say rainfall could avert that disaster. As of May 21, the Cutzamala system is at 28 percent of its capacity, according to the Basin Agency for the Valley of Mexico, a historic low.

Even though rain would help alleviate the strain on the system, it could also “cause a false sense of security” in a city that needs to use less water and create better infrastructure to make use of rainfall, said Christina Boyes, a professor of international studies at the Center for Economic Research and Teaching in Mexico City.

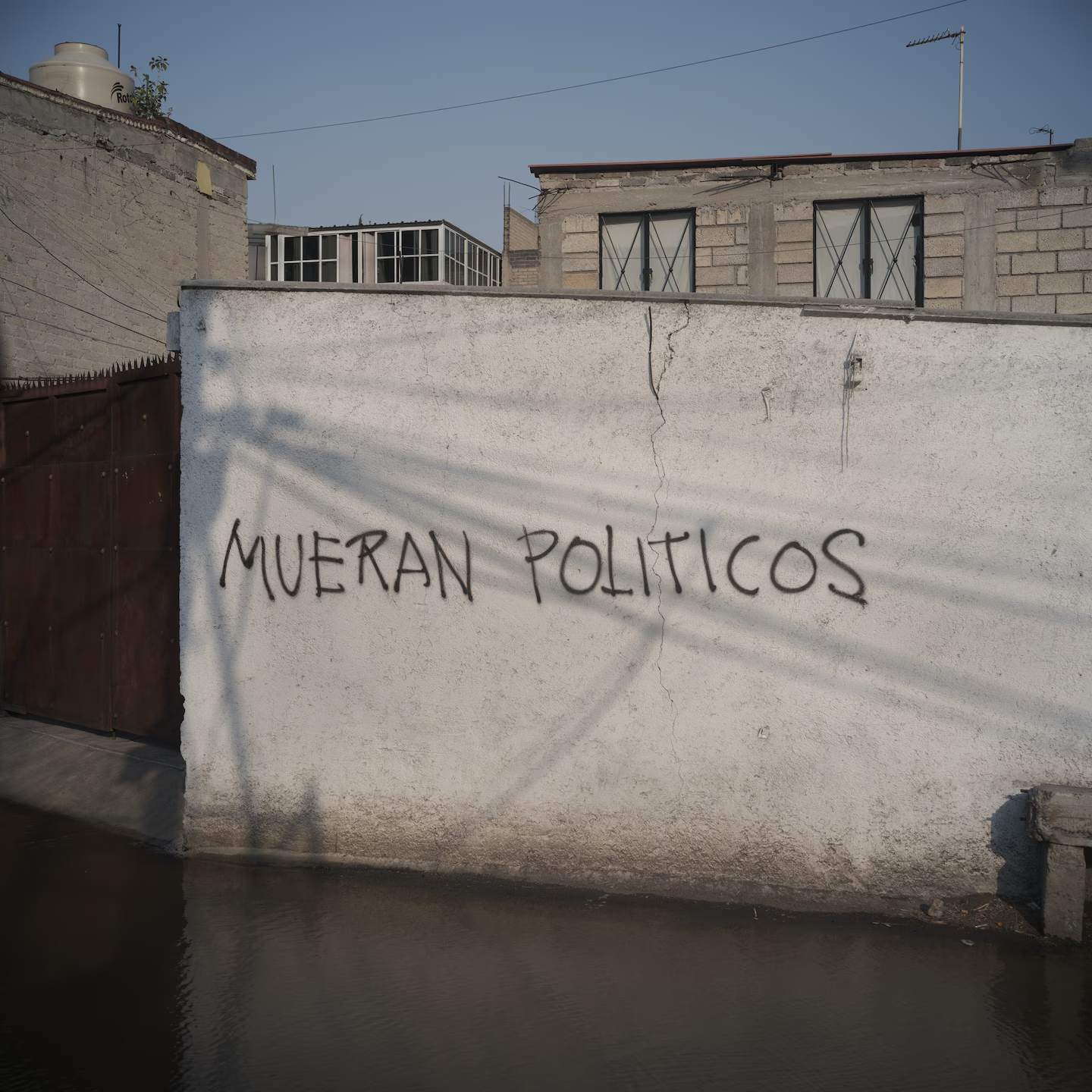

Mexico City’s water issues have become a point of contention ahead of the country’s June 2 presidential election. In a Sunday debate between Claudia Sheinbaum of Mexico’s governing Morena party, and Xóchitl Gálvez, who represents an opposition coalition, Gálvez blamed the water issues on the inaction of Sheinbaum’s party. Sheinbaum, an environmental scientist who co-authored the 2007 Nobel Prize-winning Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, is the former mayor of Mexico City.

“Right now, we are experiencing one of the worst droughts, because the Morena government did absolutely nothing to solve the problem,” Gálvez said. “Claudia, you were unable to resolve the water issue. You call yourself a scientist, you boast about your awards and today we continue with environmental emergencies.”

The following day, Sheinbaum said the ongoing drought stressed the Cutzamala system beyond expectations and decreased the supply by half. “No one could have foreseen this would happen in the city,” she said.

In the meantime, residents must find a way to adjust to water shortages — and it’s unclear for how long.

Why water supplies are low

Officials said they reduced the flow from the Cutzamala in October to save water and perform maintenance. In January, they announced cuts to hundreds of neighborhoods, mainly to the west of the city center — including wealthy neighborhoods like Polanco and Lomas de Chapultepec. Some residents protested against the low water supply.

“In Mexico City, there is a historical and critical issue of inequality in the access to water,” said Fernanda Mac Gregor, a doctoral student at National Autonomous University of Mexico who has published research on climate change risks to the city. “We are already facing many warnings and they will continue to worsen, and not only in terms of water and climate change, but in terms of inequality and poverty.”

Supplying water to 22 million people across a mountain valley is no small feat. The Cutzamala system primarily uses surface water, according to the National Water Commission (CONAGUA). The rest is pumped from underground aquifers, although that has produced significant sinking around the city.

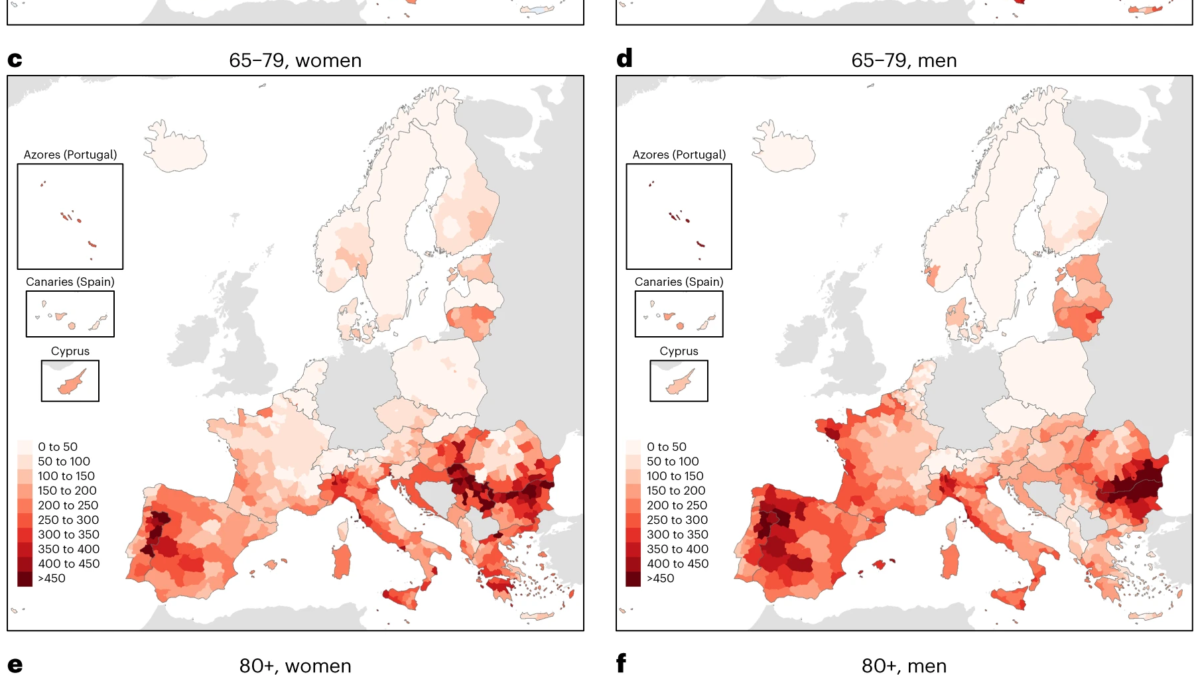

But the water in the Cutzamala system has been dwindling. In the past three years, the basin has received decreased rainfall, according to CONAGUA — about one-third less in 2022 and 2023 compared to the past 40 years, according to data from the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service.

Other factors also play a role. The recent El Niño pattern brought hotter and drier conditions last summer. Human-caused climate change has warmed Mexico around 1.6 degrees Celsius (2.9 degrees Fahrenheit) since preindustrial times. Because of the urban heat island effect, parts of Mexico City are even warmer at 3 to 4 degrees C warmer than previous decades, according to the Climate Change Research Program at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

As a result, drought has been persistent both in Mexico City and over much of the country. As of April 30, the North American Drought Monitor classified the entire federal district under a “severe” drought. The drought has caused reservoirs connected to the Cutzamala to dry up.

“It’s a complex ball of wax in predicting whether or not we’re actually going to run out [of water],” Boyes said. “I’m not sure if it’s going to rain or not, and that will make a huge difference.” [more]

Mexico City’s water ‘Day Zero’ may come even for the wealthiest residents