Flowers “giving up” on scarce insects and evolving to self-pollinate, say scientists – “Our results show that the ancient interactions linking pansies to their pollinators are disappearing fast”

By Phoebe Weston

19 December 202

(The Guardian) – Flowers are “giving up on” pollinators and evolving to be less attractive to them as insect numbers decline, researchers have said.

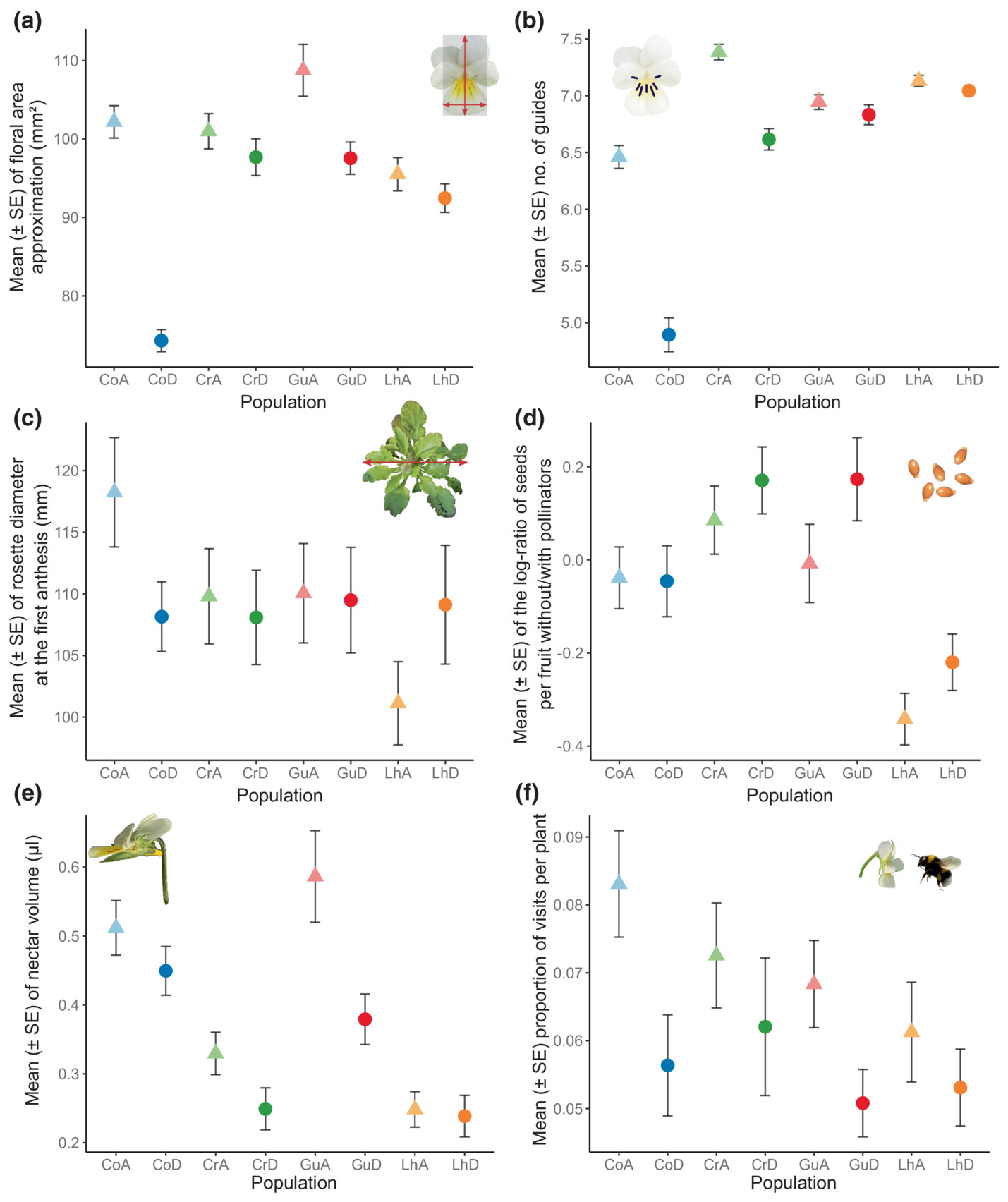

A study has found the flowers of field pansies growing near Paris are 10% smaller and produce 20% less nectar than flowers growing in the same fields 20 to 30 years ago. They are also less frequently visited by insects.

“Our study shows that pansies are evolving to give up on their pollinators,” said Pierre-Olivier Cheptou, one of the study’s authors and a researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research. “They are evolving towards self-pollination, where each plant reproduces with itself, which works in the short term but may well limit their capacity to adapt to future environmental changes.”

Plants produce nectar for insects, and in return insects transport pollen between plants. This mutually beneficial relationship has formed over millions of years of coevolution. But pansies and pollinators may now be stuck in a vicious cycle: plants are producing less nectar and this means there will be less food available to insects, which will in turn accelerate declines.

“Our results show that the ancient interactions linking pansies to their pollinators are disappearing fast,” said lead author Samson Acoca-Pidolle, a doctoral researcher at the University of Montpellier. “We were surprised to find that these plants are evolving so quickly.”

Insect declines have been reported by studies across Europe. One study on German nature reserves found that from 1989 to 2016 the overall weight of insects caught in traps fell by 75%. Acoca-Pidolle added: “Our results show that the effects of pollinator declines are not easily reversible, because plants have already started to change. Conservation measures are therefore urgently needed to halt and reverse pollinator declines.” […]

“This is a particularly exciting finding as it shows evolution happening in real time,” said Dr Philip Donkersley, from Lancaster University, who was not involved in the study.

“The fact that these flowers are changing their strategy in response to decreasing pollinator abundance is quite startling. This research shows a plant undoing thousands of years of evolution in response to a phenomenon that has been around for only 50 years. [more]

Flowers ‘giving up’ on scarce insects and evolving to self-pollinate, say scientists

Ongoing convergent evolution of a selfing syndrome threatens plant–pollinator interactions

ABSTRACT:

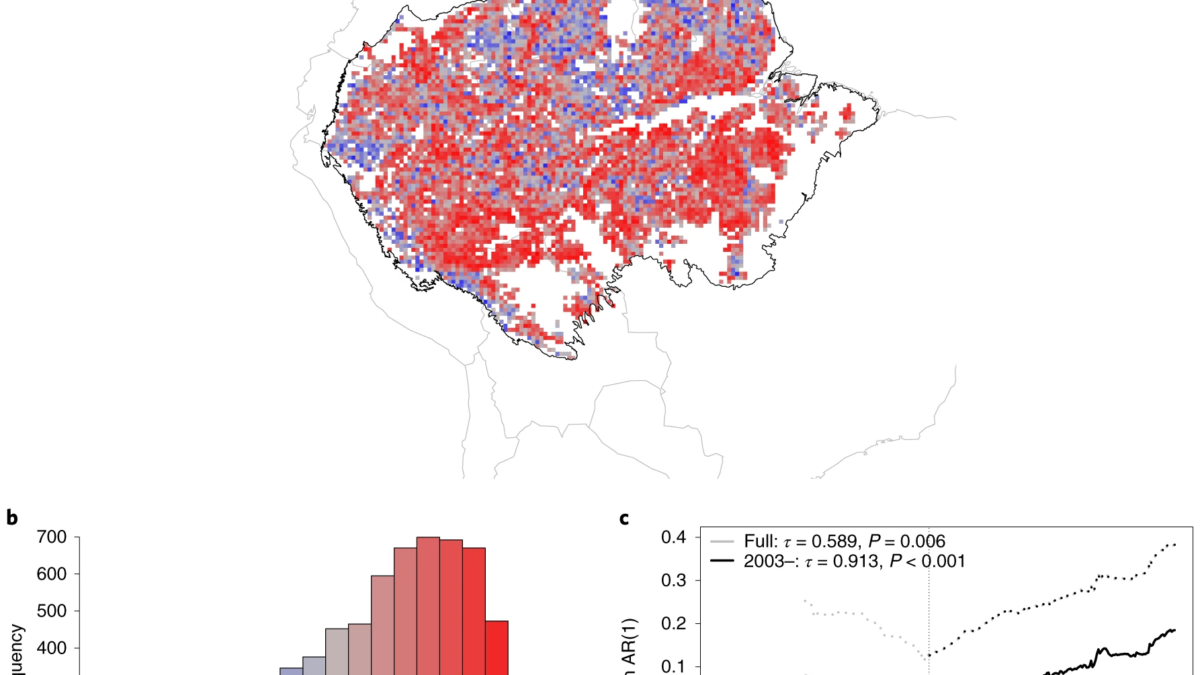

- Plant–pollinator interactions evolved early in the angiosperm radiation. Ongoing environmental changes are however leading to pollinator declines that may cause pollen limitation to plants and change the evolutionary pressures shaping plant mating systems.

- We used resurrection ecology methodology to contrast ancestors and contemporary descendants in four natural populations of the field pansy (Viola arvensis) in the Paris region (France), a depauperate pollinator environment. We combine population genetics analysis, phenotypic measurements and behavioural tests on a common garden experiment.

- Population genetics analysis reveals 27% increase in realized selfing rates in the field during this period. We documented trait evolution towards smaller and less conspicuous corollas, reduced nectar production and reduced attractiveness to bumblebees, with these trait shifts convergent across the four studied populations.

- We demonstrate the rapid evolution of a selfing syndrome in the four studied plant populations, associated with a weakening of the interactions with pollinators over the last three decades. This study demonstrates that plant mating systems can evolve rapidly in natural populations in the face of ongoing environmental changes. The rapid evolution towards a selfing syndrome may in turn further accelerate pollinator declines, in an eco-evolutionary feedback loop with broader implications to natural ecosystems.

Ongoing convergent evolution of a selfing syndrome threatens plant–pollinator interactions