California’s deadly floods won’t break the megadrought – “We are in the middle of a flood emergency and also in the middle of a drought emergency”

By Neel Dhanesha

6 January 2023

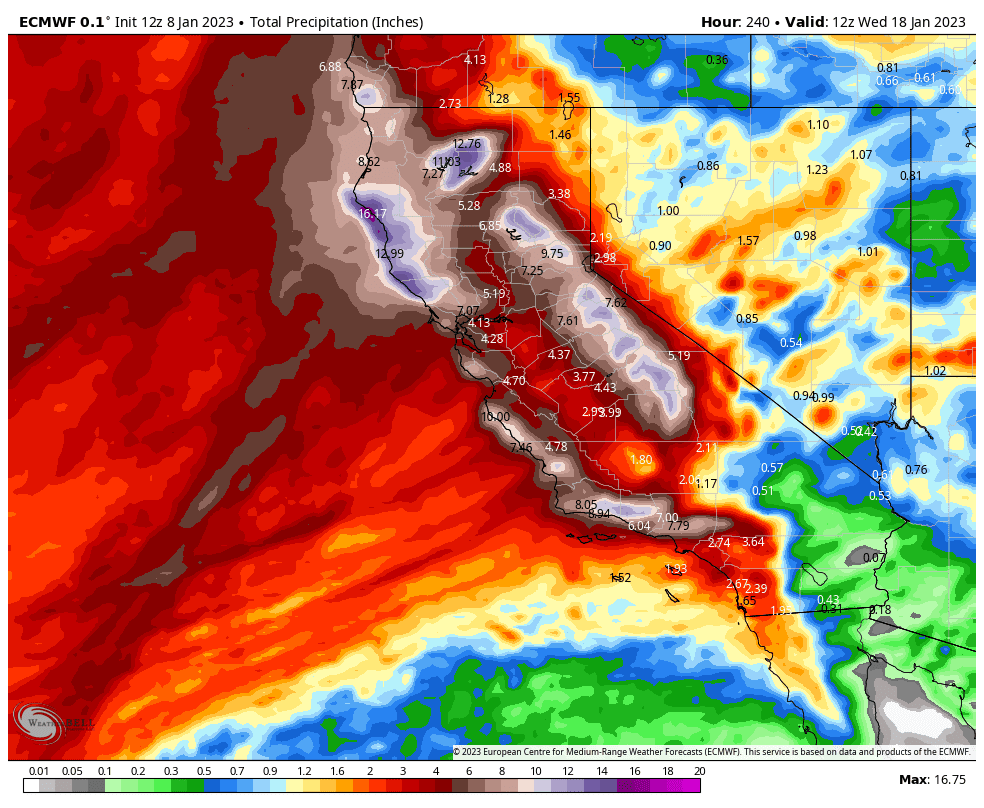

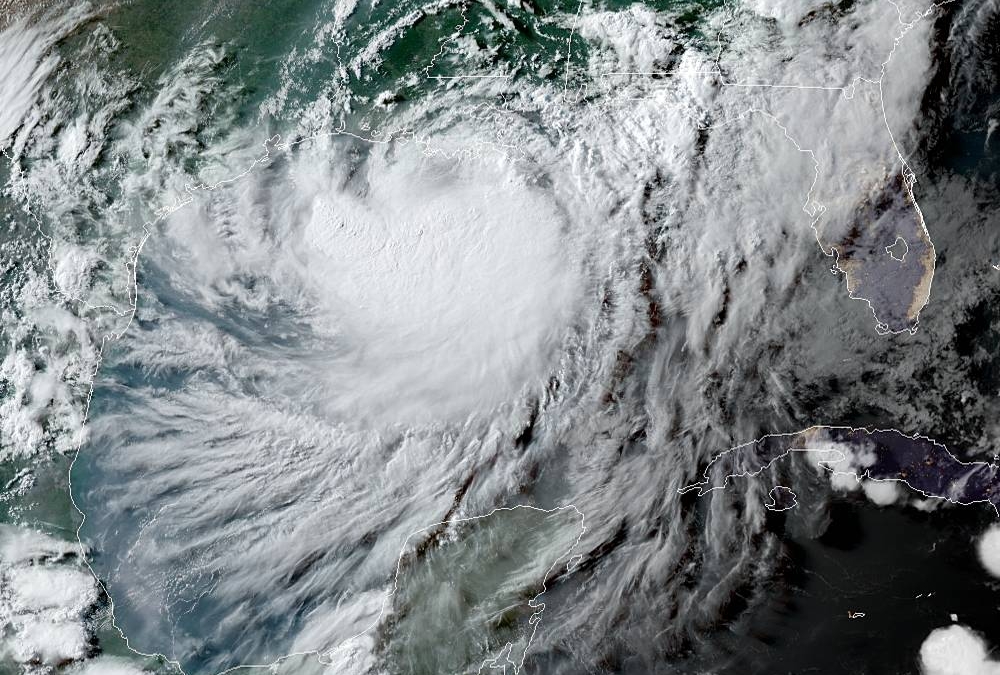

(Vox) – A “river” more than 100 miles wide is gushing through the air high above California, bringing with it heavy rain, winds, and snow. It’s the third in a series of weather systems known as atmospheric rivers — long, heavy columns of water vapor in the sky — to hit the state in the last two weeks.

It’s already proven deadly: Two people have died as a result of the storms, including a toddler; roads have flooded or been hit by mudslides, forcing evacuations; and more than 180,000 Californians lost power. On Wednesday, California Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency ahead of the storm’s arrival, and the city of San Francisco ran out of sandbags for the second day in a row as residents rushed to protect their homes from the possibility of flooding.

Once the storm passes, there will be little respite: Another atmospheric river is forecast to hit the state this coming weekend and next week, bringing even more flooding.

California is looking drenched at the moment, but for the past two decades, it’s been suffering through a megadrought of the kind that hasn’t been seen in more than 1,000 years. The drought threatens the region’s agricultural industry and ordinary citizens alike, putting livelihoods at risk and raising concerns about what the future of life in the West might look like.

Which might, understandably, raise a simple question: Can all this rain, despite the suffering it brings, help alleviate the drought?

The simple answer: Unfortunately not. A flood during a time of drought is a double disaster.

Reason 1: Too much water all at once

As we wrote last August, droughts and floods are something of a vicious cycle. It takes time for water to soak into soil, and having multiple storms hit in quick succession is something like overwatering a potted plant: The soil simply can’t take any more water. Eventually the rain turns into floods, which further erode the soil and bring the risk of downed trees, which can take out power lines and damage buildings; a 2-year-old child was killed this week when a redwood fell on a mobile home in Sonoma County.

“We are in the middle of a flood emergency and also in the middle of a drought emergency,” said California Department of Water Resources (DWR) Director Karla Nemeth in a media briefing on Wednesday. “This is an extreme weather event and we’re moving from extreme drought to extreme flood. What that means is a lot of our trees are stressed, after three years of intensive drought, the ground is saturated and there is significant chance of downed trees that will create significant problems.”

In non-drought conditions, tree roots act a bit like sponges, soaking up water from the soil. But droughts make tree roots less sponge-like, which means they can’t soak up as much water right away. That also makes the roots weaker and the trees more susceptible to falling during extreme flooding.

If the rain had been spaced out over a series of months, it might have helped with the drought by filling reservoirs over time, said Noah Diffenbaugh, a climate scientist at Stanford University’s Water in the West program. The soil would also be less saturated, allowing for more water to soak in more slowly, replenishing groundwater wells and reducing the chance of flooding.

Instead of collecting in reservoirs or soaking into the ground, the water has nowhere productive to go. So it floods. [more]