Politics, climate conspire as Tigris and Euphrates dwindle – “Life has ended here”

By Samya Kullab

18 November 2022

DAWWAYAH, Iraq and ILISU DAM, Turkey (AP) – Next year, the water will come. The pipes have been laid to Ata Yigit’s sprawling farm in Turkey’s southeast connecting it to a dam on the Euphrates River. A dream, soon to become a reality, he says.

He’s already grown a small corn patch on some of the water. The golden stalks are tall and abundant. “The kernels are big,” he says, proudly. Soon he’ll be able to water all his fields.

Over 1,000 kilometers (625 miles) downstream in southern Iraq, nothing grows anymore in Obeid Hafez’s wheat farm. The water stopped coming a year ago, the 95-year-old said, straining to speak.

“The last time we planted the seed, it went green, then suddenly it died,” he said.

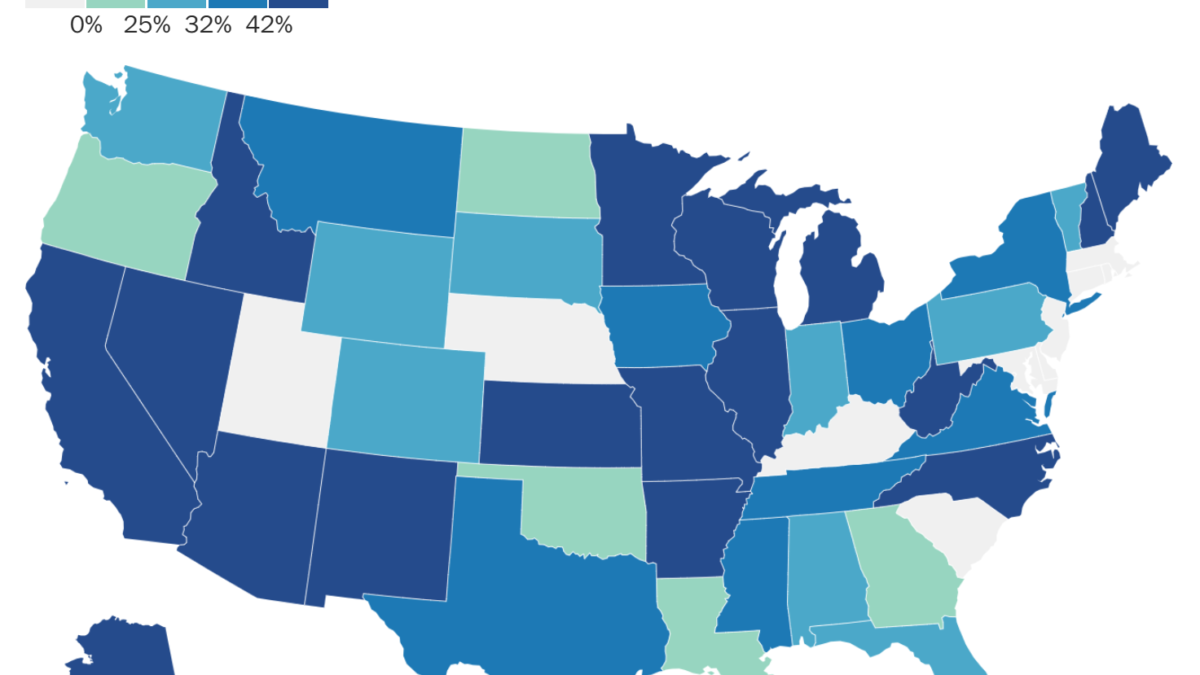

The starkly different realities are playing out along the length of the Tigris-Euphrates river basin, one of the world’s most vulnerable watersheds. River flows have fallen by 40% in the past four decades as the states along its length — Turkey, Syria, Iran and Iraq — pursue rapid, unilateral development of the waters’ use.

The drop is projected to worsen as temperatures rise from climate change. Both Turkey and Iraq, the two biggest consumers, acknowledge they must cooperate to preserve the river system that some 60 million people rely on to sustain their lives.

But political failures and intransigence conspire to prevent a deal sharing the rivers.

The Associated Press conducted more than a dozen interviews in both countries, from top water envoys and senior officials to local farmers and gained exclusive visits to controversial dam projects. Internal reports and revealed data illustrate the calculations driving disputes behind closed doors, from Iraq’s fears of a potential 20% drop in food production to Turkey’s struggles to balance Iraq’s and its own needs.

“I don’t see a solution,” said former Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi.

“Would Turkey sacrifice its own interests? Especially if that means that by giving more (water) to us, their farmers and people will suffer?” […]

“A single truth”

Iraq is the downstream prisoner of geography, relying almost entirely for its water on the twin rivers and tributaries originating outside its borders.

In 2014, Iraq’s Water Ministry prepared a confidential report that spelled out a “single truth:” In two years, Iraq’s water supply would no longer meet demand, and the gap would keep widening. The report, seen by the AP, warned that by 2035, the water deficit would cause a 20% reduction in food production.

The doomsday predictions are playing out in 2022. Lakes have dried up, crops have failed, and thousands of Iraqis are migrating. An author of the report, who spoke anonymously because it is not public, said the predictions were “remarkably accurate.”

They show Iraqi officials knew how bleak the future would be without the recommended $180 billion in investment and an agreement with neighbors. Neither transpired.

Decades of talks have still not found common ground on water-sharing. […]

“Your eyes, your scale”

Sheikh Thamer Saeedi decided enough is enough. The streams were dry in his village in southern Iraq. Despairing families were abandoning their farms for the city after crops failed.

What he did next underscores rising anger among farmers following devastating, back-to-back droughts — and the Iraqi government’s weaknesses that make managing water nearly impossible.

“One week,” Saeedi told local water authorities in Dhi Qar province. Release more water to his district, Dawwayah, he threatened, or else he would take matters into his own hands.

In Iraq’s south, tribal allegiance transcends government authority. As a tribal leader, Saeedi had to guarantee water for his people to safeguard his legitimacy.

The authorities were in a bind. Water levels in the Gharraf River, the Tigris’ branch here, were so low it didn’t reach the diversion gates, designed in the 1970s when flows were twice as high. Districts like Dawwayah, further along the irrigation network, were left dry.

At the same time, the government had cut the province’s water allocation by 60%.

Time ran out.

Saeedi marched with dozens of followers to the irrigation regulator on the riverbank, armed with a long pipe and shovels. They dug until a water corridor was secured to his district.

“My people are thirsty,” he said.

To ensure he left enough water for other communities, Saeedi invoked the Arabic idiom: “Your eyes, your scale.” That is, he took a wild guess.

Rival tribal leaders were enraged, fearing for their own water supplies. Security officials rushed to put a halt to the diversion. Many feared gun battles if they hadn’t.

“It was a destructive act,” said Ghazwan Kadhim, head of Dhi Qar’s Water Resources Directorate. “The Gharraf River has 154 gates to different areas. If anyone does anything like that, the entire river would become unfit for distributing water.”

But authorities are having a harder time keeping a lid on fights over water. Threats of lawsuits do little to stop tribal leaders diverting flows or digging illegal wells; using security forces risks escalation.

“We are terrified of conflict breaking out in central and southern Iraq over the water shortages,” said Issa Fayadh, an official at the Environment Ministry in Baghdad. […]

“Life has ended”

In the famed Chibayish marshes, the carcasses of water buffalos float along the riverbanks, poisoned by the salty water.

Herders circulate the iconic wetland, fabled to have been the biblical Garden of Eden, looking for trickles of fresh water to save their animals.

Over the past two years, the lush greenery of the marshes has degenerated and yellowed, killed by salinity building up from two years of insufficient fresh-water inflow.

It is a haunting vision of the future. Along with dying livestock, harvests are declining for a second year in a row; both are the principal employers in rural Iraq. At least 62,000 in south-central Iraq have migrated to congested urban centers due to drought, the U.N. reported in September.

Obeid Hafez, the elderly farmer, once produced nearly 2,500 acres of wheat. Today his lands in southern Iraq are barren.

Portraits of Hafez’s forefathers hang in his spartan living room. Their stern faces look down on him as he speaks.

He inherited the lands from them, one generation to another.

But there will be no one to come after him. His sons have gone, looking for work in the cities.

“Life has ended here,” he said. [more]