Deforesters are plundering the Amazon. Brazil is letting them get away with it. – “No one goes to jail. They deforested 50 square miles. There were 23 arrests. In the end, no one’s in jail. And this was the biggest deforestation ring in Brazil.”

By Terrence McCoy

30 August 2022

BRASILÉIA, Brazil (The Washington Post) – Daniel Valle sped down Highway 317, closing in on the first targets of the day. He was in a hurry. Deforestation alerts had tripled in recent weeks. Police were warning that armed criminal groups had invaded new territory. Another season of destroying the Amazon rainforest was here, and in this corner, the only check on the looming ecological disaster was this: Valle’s small team of inspectors in a dirt-splattered pickup truck.

“This is it,” said Valle, 39, pulling off the highway. A roving state environmental inspector, he traveled throughout this remote land that was increasingly under threat from a wave of destruction that had leveled the forests to the east. His job was to slow its advance. The challenge felt futile most days. But especially today.

His crew was in southern Acre, where the federal government under President Jair Bolsonaro — a longtime critic of environmental regulation — no longer staffed a single inspector. That meant his state agency, the Acre Environmental Institute, now bore the burden of enforcing environmental law in this area of more than 3,600 square miles along the border with Bolivia.

Valle pulled out his target list. The map showed 16 points of illegal devastation — pinpricks of red piercing an expanse of green and brown.

He sighed. This was enough work for two weeks. Not the two days they’d been given.

“We don’t have enough people,” Valle said.

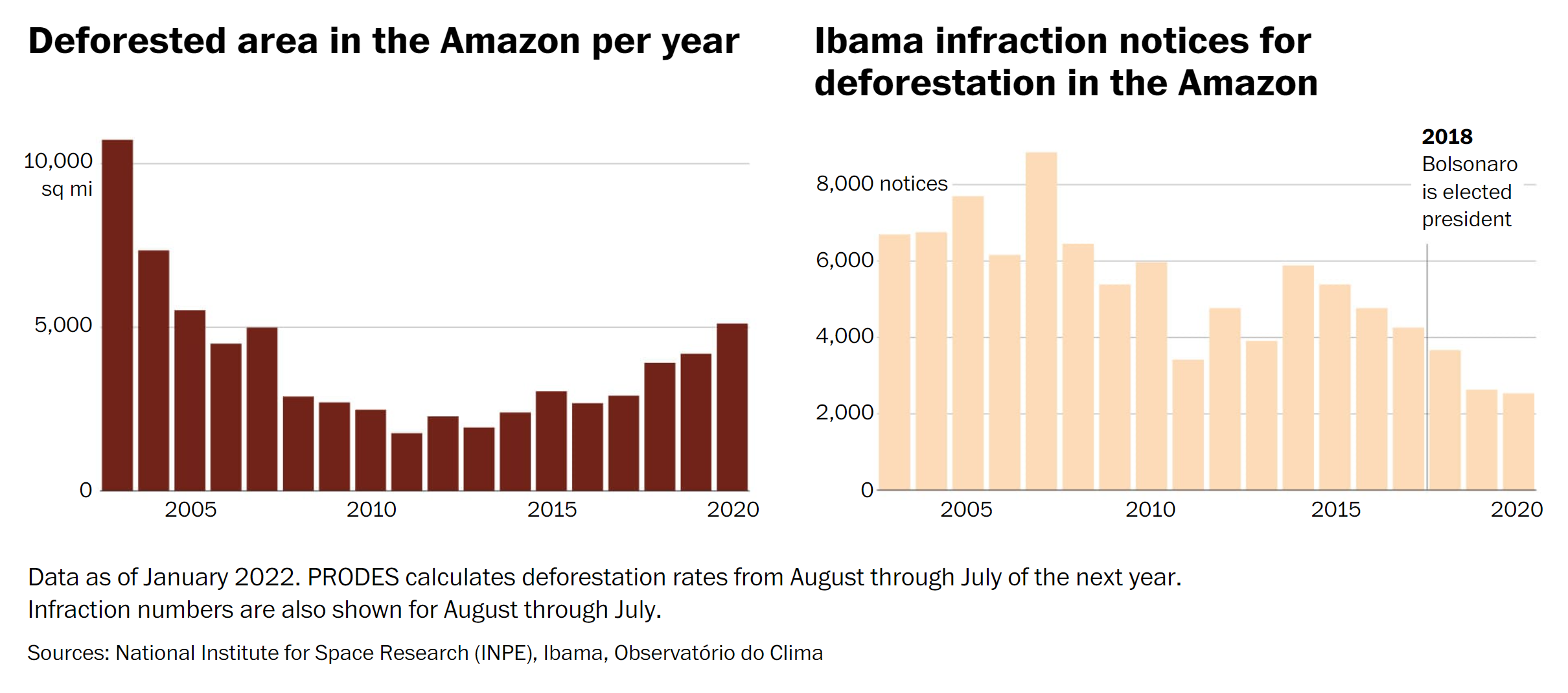

This mismatch — too few inspectors for too much deforestation — is one of a cascading series of shortfalls and failures that are enabling criminals to raze the world’s largest rainforest with impunity. Law enforcement misses the majority of deforestation in the Amazon. The fines that the few state and federal inspectors here write are seldom paid. The occasional cases that spill into the criminal justice system languish for years. And in the rare instance of a criminal conviction, it almost never draws a prison sentence, The Washington Post found in a review of a year’s worth of cases.

The violent and lawless erasure of the Amazon is perhaps the world’s greatest environmental crime story. Scientists warn that the forest, seen as vital to averting catastrophic global warming, is at a tipping point. But in Brazil, home to about 60 percent of the Amazon, nearly one-fifth has already been destroyed. And virtually no one, law enforcement officials say, has been held accountable.

“No one goes to jail,” said Luciano Evaristo, former chief inspection officer of Ibama, the federal environmental law enforcement agency. “For example, in 2016, we took apart a large deforestation ring in the south of Pará state. They deforested 50 square miles. There were 23 arrests. In the end, no one’s in jail. And this was the biggest deforestation ring in Brazil.”

Environmental agencies have similarly struggled to punish even those accused of only minor deforestation — such as the man the inspection team was driving to visit. At the end of the path, they found rancher Francisco Nonato de Souza coming out of his house. They accused him of illegally deforesting 45 acres and handed him a $17,000 fine.

Nonato glowered. He looked at the crew’s heavily armed police escort.

“You come out here for this bit of deforestation but do nothing about the guys who deforest 120 or 150 acres?” he said. “Those guys over there” — his chin jutting into the distance — “they knocked it all down. Burned it. Planted grass. Nothing happened to them.”

Valle defended their work. Nonato was the first on their list in southern Acre. But they still had 15 cases to investigate.

The rancher was unmoved.

“They knock it all down,” he said. “And nothing happens.” [More]

Deforesters are plundering the Amazon. Brazil is letting them get away with it.