How Russia, China, and Iran shaped and manipulated coronavirus vaccine narratives

By Bret Schafer, Amber Frankland, Nathan Kohlenberg, and Etienne Soula

6 March 2021

(ASD) – When Vladimir Putin announced last August that Russia had granted regulatory approval for Sputnik V, the world’s first coronavirus vaccine, it signaled—albeit perhaps prematurely—not only a potential turning point in the fight to end the coronavirus pandemic but also a new phase in the global contest to shape and at times manipulate information around the virus and its origins, treatments, and potential cures.

That vaccines have become the latest flashpoint in the coronavirus-era battle of narratives is hardly surprising. Since the outbreak of the virus forced much of the world into lockdown last March, Russia, China, and Iran have used a combination of public diplomacy, propaganda, and overt and covert disinformation campaigns to portray their respective responses to the pandemic as superior to those of the West.

Vaccine diplomacy is a natural extension of these efforts. The ability to develop and distribute an effective vaccine is, like mask diplomacy before it, an effective tool for autocrats to blunt domestic and international criticism and to showcase the competency and generosity of their respective governments. But with more than a half-dozen vaccines in early or limited use, vaccine narratives are more than an exercise in self-promotion; they are a tool to open enormous diplomatic and economic opportunities for vaccine-producing countries. The stakes are therefore elevated, as attempts to win the hearts, minds, and deltoids of global publics—particularly those in developing countries—is as much about market dominance as it is about soft power.

To date, much has been written about Russia and China’s use of information operations to manipulate coronavirus narratives, including around vaccines. These reports have largely relied on specific examples of Russian and Chinese actors promoting stories that have toed a fine line between sensationalism and outright disinformation. The focus on disinformation is understandable; however, this approach risks missing the steady drumbeat of factual but, in aggregate, misleading coverage that can shape public opinion over time. It has also allowed those countries and their state media outlets to claim that their reporting has been misrepresented. For example, in a statement made to The New York Times about allegations of disingenuous vaccine reporting by Russian state media outlets in Latin America, RT alleged that the stories referenced in the Times’ article represented “a cherry-picked fraction of our coverage” and did not contain “any inaccuracies or falsehoods.”1

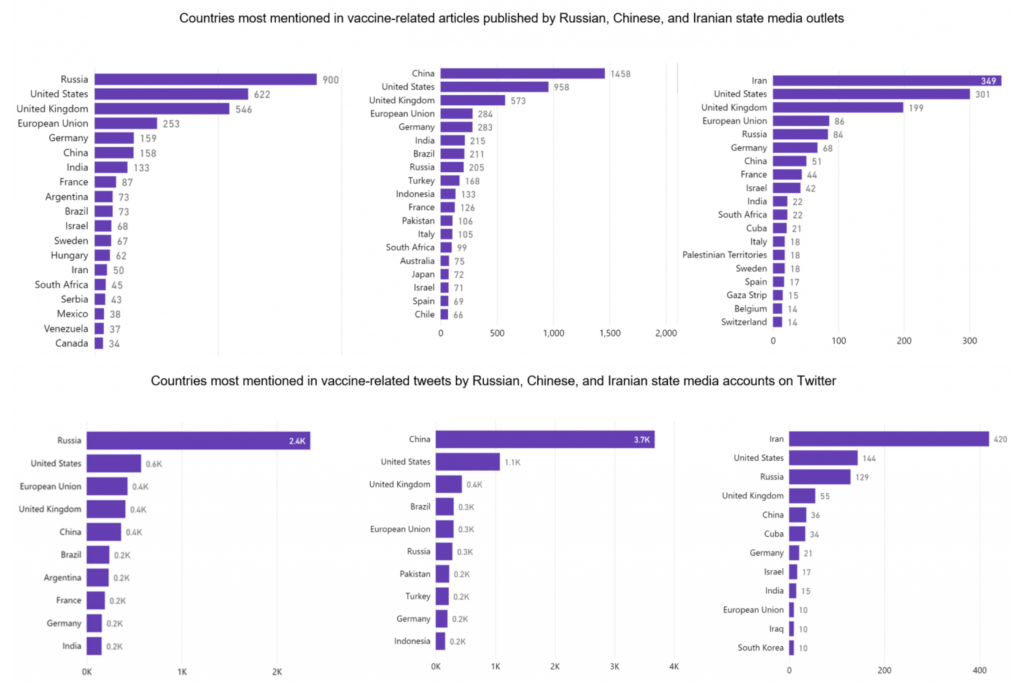

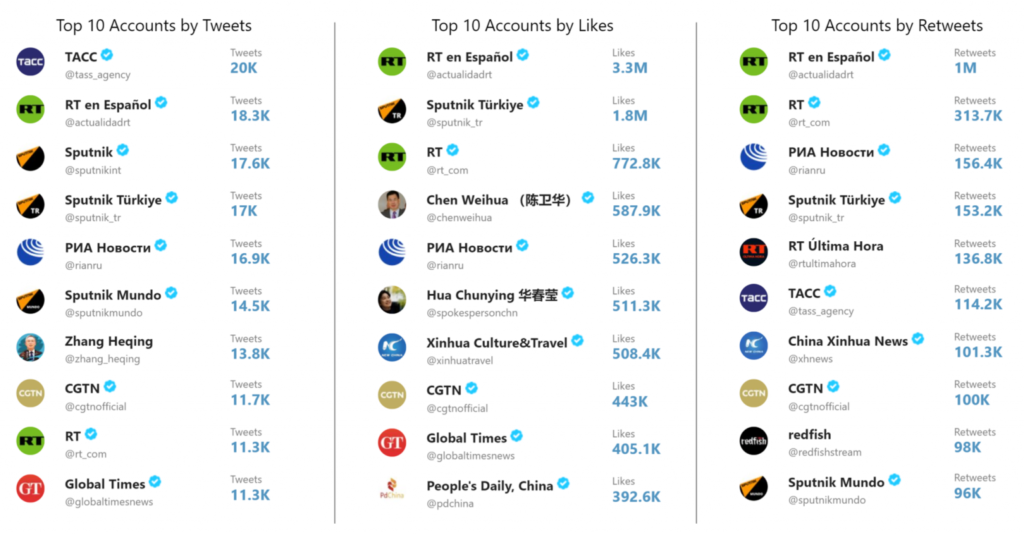

To test these and other claims, this report analyzes more than 35,000 vaccine-related messages captured by ASD’s Hamilton 2.0 dashboard, an open-source tool that collects and displays outputs from Russian, Chinese, and Iranian diplomats, government officials, and state media outlets on Twitter, YouTube, and state-sponsored news websites. Although this report highlights vaccine-related narratives promoted across multiple platforms, comparative analysis was conducted on Twitter data collected during a three-month period commencing on November 9, 2020, the day Pfizer-BioNTech announced it had successfully completed its phase 3 trial. The studied time frame (November 9, 2020-February 9, 2021) also covers the announcements of several major vaccine developments, including the European Union’s decision to authorize the use of the Moderna and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines and China’s approval of its homegrown Sinovac and Sinopharm vaccines.

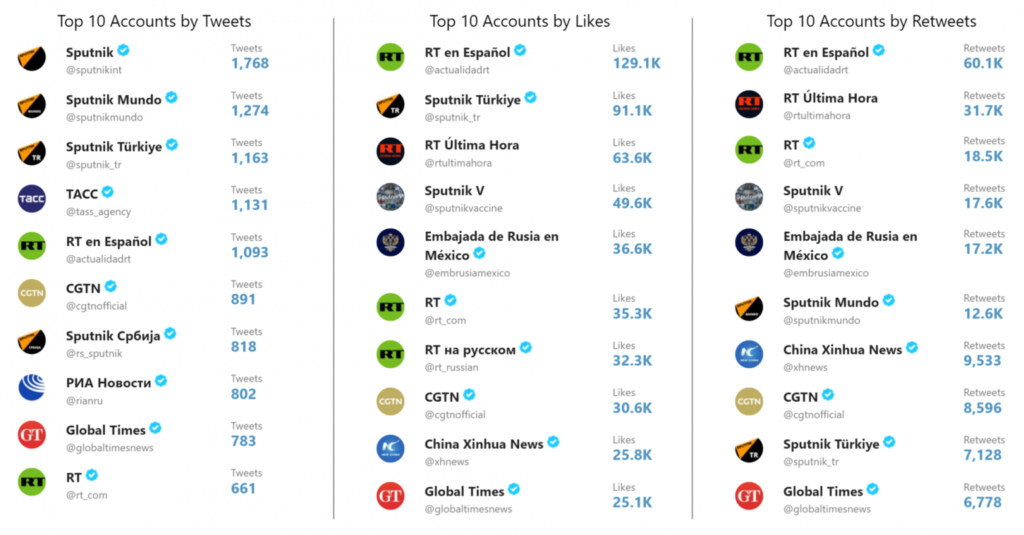

During the studied period, ASD collected more than 455,757 tweets from Russian, Chinese, and Iranian officials and state media outlets. Of those tweets, 29,601 contained the text “vaccin*” (a search term that captures multiple iterations of the words “vaccine” and “vaccination”), representing a nearly threefold increase in vaccine-related coverage compared to the three months prior to Pfizer’s announcement. (A search for vaccin* returned 13,250 hits been August 9, 2020 and November 9, 2020 versus 33,702 hits between November 9, 2020 and February 9, 2021.) Researchers also queried the manufacturers of the three EU-approved vaccines (Pfizer, Moderna, and Oxford-AstraZeneca),2 as well as Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine and China’s Sinovac and Sinopharm vaccines. In order to provide a baseline for comparison, ASD also analyzed over 10,000 vaccine-related tweets from a control group of global media outlets.

This report covers the two-prongs of each country’s external messaging campaigns around vaccines: promotion of domestically produced vaccines, and coverage of vaccines produced by other countries. Within those broad categories, particular attention was given to analyzing the most salient themes, the most influential accounts and outlets, the most targeted countries, and the vaccines that received the most and least positive coverage. Importantly, this paper only covers overt messaging, meaning that notable instances of disinformation from covert sites were not analyzed.

Key findings

- While there were few instances of any studied country promoting verifiably false information about vaccines, reports of safety concerns related to the administration of certain Western-produced vaccines were often sensationalized while downplaying or completely omitting key contextual information. For example, Iran’s Arabic-language Fars News Agency tweeted that the Pfizer vaccine “kill[ed] six people in America,” omitting (and never correcting) that four of the six people who died during the vaccine trial had received a placebo and that authorities determined there was no causal connection between the vaccine and the deaths of the other two participants.

- Of the three COVID-19 vaccines authorized for use by the European Commission, the Pfizer vaccine was mentioned more often by Russian, Chinese, and Iranian accounts than the Moderna and AstraZeneca vaccines combined.

- Pfizer received by far the most unfavorable coverage of any vaccine, particularly from Kremlin-funded outlets and Iranian state media and government accounts. Of the 50 most-retweeted tweets mentioning Pfizer posted by Russian state media outlets, 43 (86 percent) mentioned either an adverse reaction to the vaccine (including deaths) or negative information about the company itself. In Iranian government and state media tweets, 92 percent of mentions of Pfizer were negative. But the notion that Russian, Chinese, and Iranian diplomats and state media outlets seek to disparage and undermine Western vaccines writ large is not entirely accurate, as coverage of Moderna’s vaccine was mixed and reporting on Oxford-AstraZeneca’s vaccine was largely neutral or positive.

- Russia was the most likely of the three studied countries to suggest linkages between the Pfizer vaccine and the subsequent deaths of vaccine recipients. Of the 209 tweets from Russian, Chinese, and Iranian accounts that mentioned Pfizer and the words “die,” “dead,” or “death” in the same tweet, 111 (53 percent) were from Russian state media outlets.

- It is unclear why Pfizer received more negative coverage than Moderna, though possible explanations include: a) they were the first Western vaccine to be approved and therefore were viewed as the primary competition to Russian and Chinese vaccines, b) there have been safety concerns that have popped up that made them an easy target for mal-information campaigns, and c) they are simply a more globally recognizable U.S. brand than Moderna and thus served as a better target for anti-Big Pharma campaigns.

- Russia’s coverage of Oxford-AstraZeneca took a noticeable U-turn after a December announcement of a deal to test a combination of the Oxford-AstraZeneca and Sputnik V vaccines. After the announcement, there was an increase in positive reporting and a reduction in negative coverage of AstraZeneca in Russian diplomatic and state media outputs.

- Russia and China aggressively promoted their own vaccines, but not one another’s. In Russian tweets that mentioned a vaccine by name, just over 6 percent mentioned one of the two Chinese vaccines. Similarly, in Chinese tweets that mentioned a vaccine by name, just under 3 percent mentioned Sputnik V. By comparison, our control group of global media accounts mentioned Sputnik V in 6.5 percent and the two Chinese vaccines in over 8 percent of tweets that mentioned a vaccine by name.

- Russian, Chinese, and Iranian state media outlets all promoted the theory that “mainstream” or “Western” media outlets provided biased coverage of Russian and Chinese vaccines and ignored safety concerns related to Western vaccines. These claims were not supported by a review of tweets from our control group of global media outlets. For example, of the 23 tweets from U.S.-government-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty that mentioned Sputnik V, only 4 (17 percent) were negative. Major incidents that the western press was accused of ignoring—most notably, deaths in a Norwegian nursing home after the administration of the Pfizer vaccine—were covered by surveyed Western outlets, though with far more context.

- Iran’s coverage of Pfizer and Moderna took a decidedly more negative turn after Ayatollah Khamenei’s decision on January 8, 2021 to ban the importation of all vaccines produced in the United States and the United Kingdom. Despite the ban, Iran continues to move forward with plans to import AstraZeneca, a contradiction that state media justified by claiming that the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine is Swedish, not British. Relatedly, AstraZeneca’s coverage was entirely positive, indicating that Iran’s coverage is motivated by need as much as geopolitics.

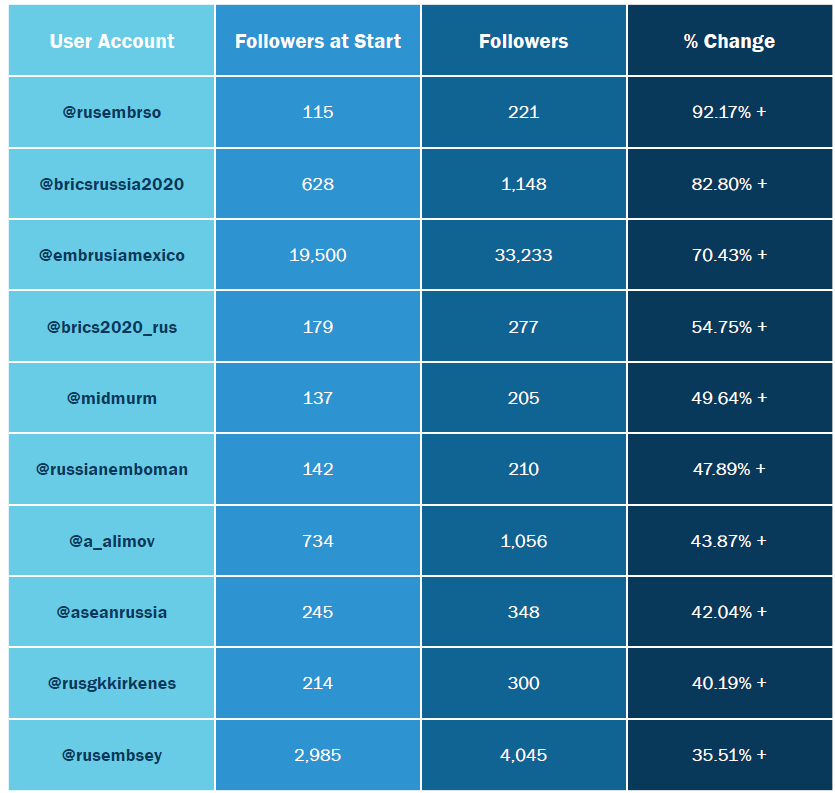

- Twitter accounts affiliated with Russian and Chinese embassies in countries that either approved or were in the process of approving Russian or Chinese vaccines gained more followers and received substantially more engagement than diplomatic accounts in other countries.

- On a per-tweet basis, vaccine-related tweets from the Russian Embassy in Mexico received the most retweets and likes of the more than 900 accounts surveyed—outpacing state media accounts with a hundred times more followers. Mexico granted emergency approval for the Sputnik V vaccine in early February. […]

Conclusion

ASD’s analysis uncovered sometimes subtle and sometimes stark differences in how state media and diplomats from Russia, China, and Iran cover specific vaccines. A universal feature of their reporting, however, was an effort to convince audiences, both at home and abroad, that their domestically produced vaccines (or, in the case of Iran, vaccines approved for domestic use) were safer, more effective, more practical, and more affordable than vaccines produced by their Western competitors. Coverage of these issues often tied into tropes that are commonly woven into each country’s coverage of a range of topics, including claims of mainstream media bias, xenophobia, and the failures of capitalism and democratic systems.

These themes, implicitly and explicitly, were peppered throughout each country’s vaccine-related messages. They also formed the backbone of Russia and China’s pitch to developing countries. China, for example, emphasized that its vaccines are “global public goods” that are more practical for distribution in the Global South (as opposed to Western vaccines that are created for profit, require cold storage, and are being prioritized for the “world’s rich”). Russia emphasized the cost-per-jab advantage of Sputnik V, as well as the safety and efficacy of their vaccine. Undergirding it all was the common refrain that Chinese and Russian vaccines were being ignored or slandered by the corrupt mainstream media or malign Western agendas—a claim that our research suggests is inflated if not entirely inaccurate.

While Russia and China’s promotion of their domestically produced vaccines was expected, the three studied countries’ coverage of surveyed Western vaccines revealed more nuance than was anticipated. Contrary to the belief that Russia, China, and Iran have indiscriminately targeted all Western vaccines with negative messaging campaigns, our data indicates that their information strategies represent a balancing of public health needs, economic pursuits, geopolitical posturing, and other strategic interests.

Finally, our analysis also revealed that while there were few instances of any of the three countries engaging in outright disinformation, their reporting on safety issues—especially related to the Pfizer vaccine—was frequently misleading. And these half-truths and exaggerations, repeated as often as they were, were arguably just as damaging as falsehoods, and certainly harder to fact-check and moderate. This suggests that more attention should be given to the study and mitigation of mal-information—information that is technically true but that is intentionally presented without context—as the effect of such information is clear, but the remedies are less obvious. [more]