The age of stability is over, and coronavirus is just the beginning – “Our modern interconnected global economy is much more vulnerable than we thought”

By Wolfgang Knorr

16 April 2020

(The Conversation) – Humanity has only recently become accustomed to a stable climate. For most of its history, long ice ages punctuated with hot spells alternated with short warm periods. Transitions from cold to warm climates were especially chaotic.

Then, about 10,000 years ago, the Earth suddenly entered into a period of climate stability modern humans had never seen before. But thanks to ever accelerating emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, humanity is now bringing this period to an end.

This loss of stability could be disastrous. If the coronavirus pandemic can teach us anything about the climate crisis it is this: our modern interconnected global economy is much more vulnerable than we thought, and we must urgently become more resilient and better prepared for the unknown.

After all, a stable climate underpins much of modern civilisation. About half of humanity depends on stable monsoon rains for food production. Many agricultural plants need certain temperature variations within a year to produce a stable crop, and heat stress can damage them greatly. We rely on intact glaciers or healthy forest soils to store water for the dry season. Heavy rains and storms can wipe out the infrastructure of whole regions.

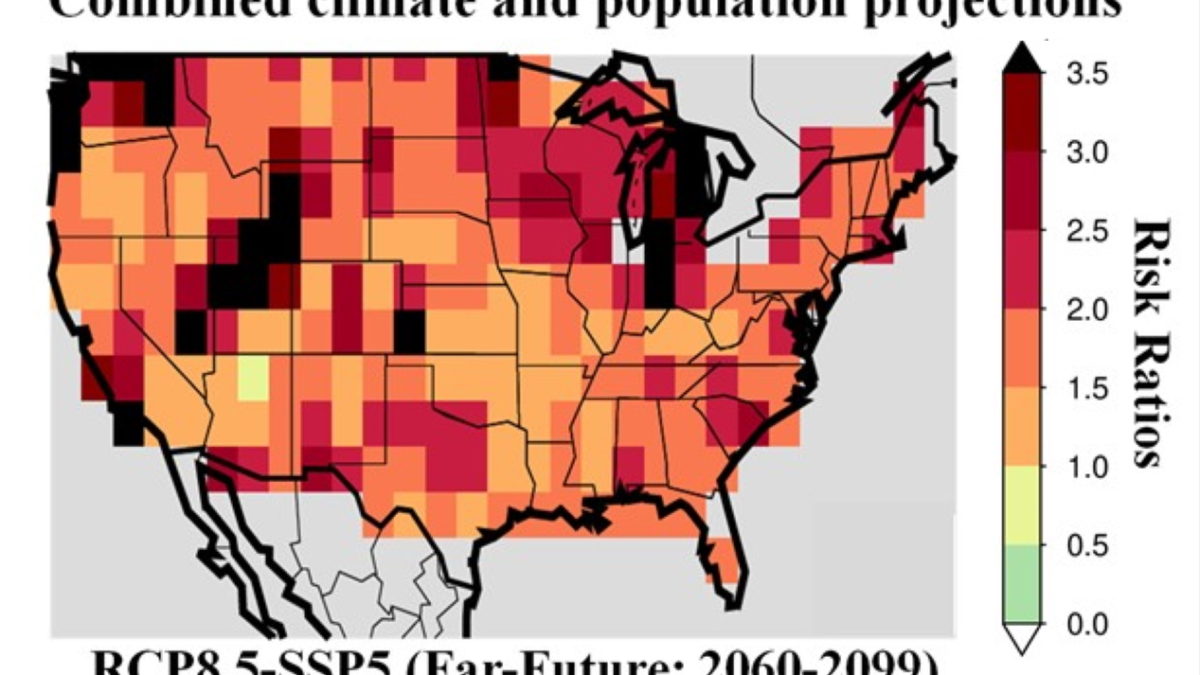

These are the sorts of climate impacts that we know about, and have been extensively studied by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). But the biggest risk may yet come from climate-related chaos that we did not expect.

Impossible heatwaves – in consecutive years

In 2018, a prolonged heat wave and drought hit much of western and northern Europe and decimated much of the potato harvest in the region. Temperatures in my native Germany reached record highs in a summer that was drier and hotter than in many parts of the Mediterranean. Climate models had predicted Europe’s most extreme heat increases would occur in Greece, Turkey and Ukraine, so the odds of such a heatwave seemed impossibly low. [more]

The age of stability is over, and coronavirus is just the beginning