U.N. warns that runaway inequality is destabilizing the world’s democracies – “Efforts to reduce inequality will inevitably challenge the interests of certain individuals and groups. At their core, they affect the balance of power.”

By Christopher Ingraham

11 February 2020

(The Washington Post) – Runaway inequality is eroding trust in democratic societies and paving the way for authoritarian and nativist regimes to take root, according to a dire new report from the United Nations.

The findings note that solutions — including robust social safety nets, an active redistribution of wealth and the protection of workers rights — “have been recommended for decades” and are well within the capacity of the world’s wealthy nations.

But in many countries, including the United States, such initiatives have been blocked by “economic elites” because they inevitably threaten the interests of certain stakeholders, the report says, affecting the balance of power in nations that pursue greater economic redistribution.

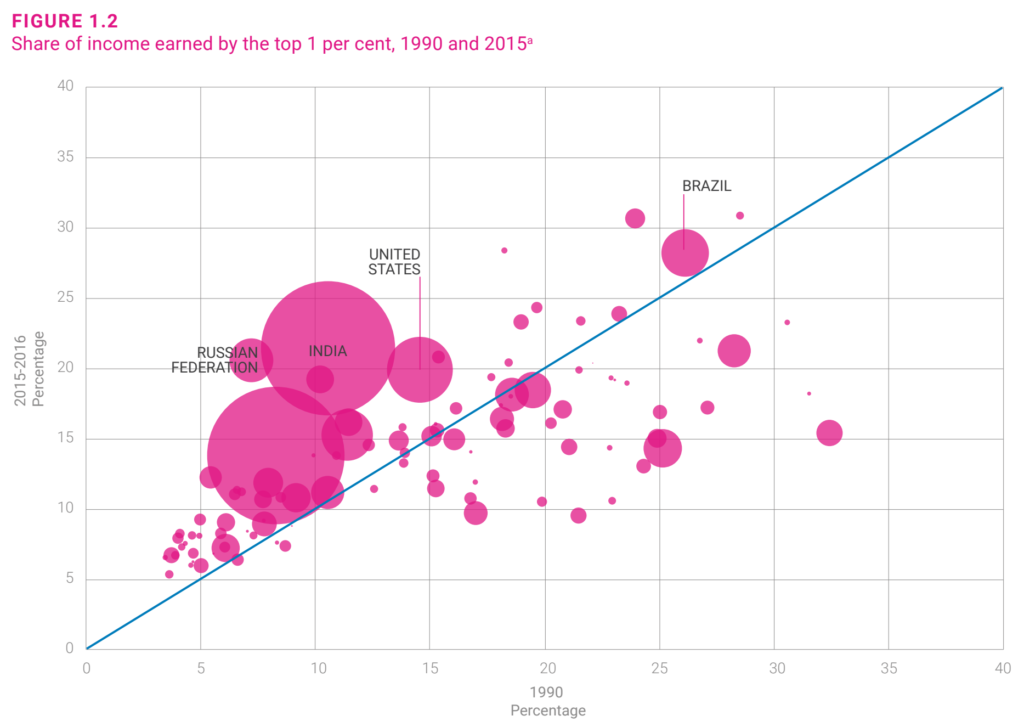

The broad contours of income and wealth inequality in the United States are, at this point, well-known. The top 1 percent of households have roughly doubled their share of the nation’s wealth since 1980, leaving less behind for everyone else. The 400 richest Americans now have significantly more money than the 150 million Americans in the bottom 60 percent of the distribution.

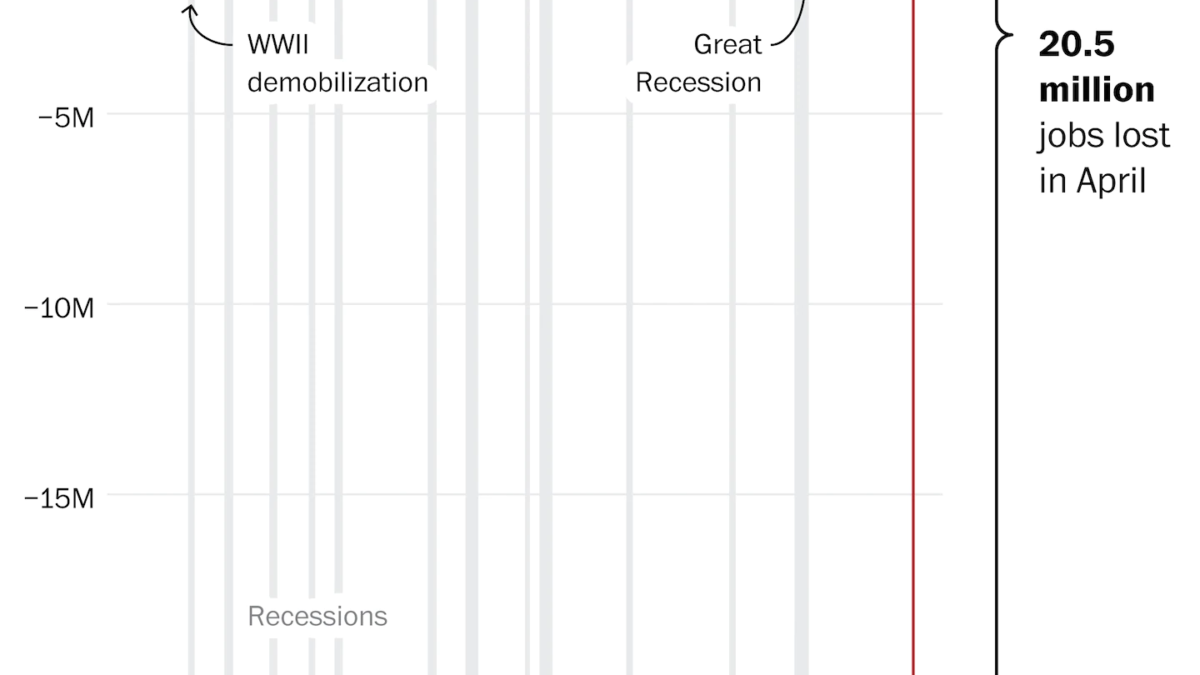

In the past several decades, paychecks of rank-and-file workers have stagnated even as they have delivered on the growing profits demanded by their bosses and shareholders. As the U.N. report notes, the average compensation for a chief executive at a Standard & Poor’s 500 company was $14.5 million in 2018, while the average production and nonsupervisory worker took in about $40,000.

Defenders of the economic status quo have argued, at times, that inequality is probably not rising all that much. But even if it is, it may well be the inevitable byproduct of a capitalist society and, in fact, it might actually be good. Economic inequality, in this view, is simply the price of paying a fair remuneration to the people who produce the iPhones and the cool apps and the free shipping that all of us — even the less fortunate — are now able to enjoy.

The U.N. report notes, however, that rampant inequality is harmful even to people at the top of income and wealth distributions. Unequal societies “grow more slowly and are less successful at sustaining economic growth,” as numerous studies have shown. As economic conditions deteriorate in lower and middle classes, we may get to a point where a critical mass of the population can no longer afford the iPhones and cool apps and free shipping that are driving our economy, causing a recession. In the end, the trouble with capitalism may be that eventually you run out of other people’s money.

The U.N. report is unusually clear-eyed on the power dynamics underlying today’s inequality struggles. “People in positions of power tend to capture political processes, particularly in contexts of high and growing inequality,” the report states. “Efforts to reduce inequality will inevitably challenge the interests of certain individuals and groups. At their core, they affect the balance of power.” [more]

U.N. warns that runaway inequality is destabilizing the world’s democracies

World Social Report 2020

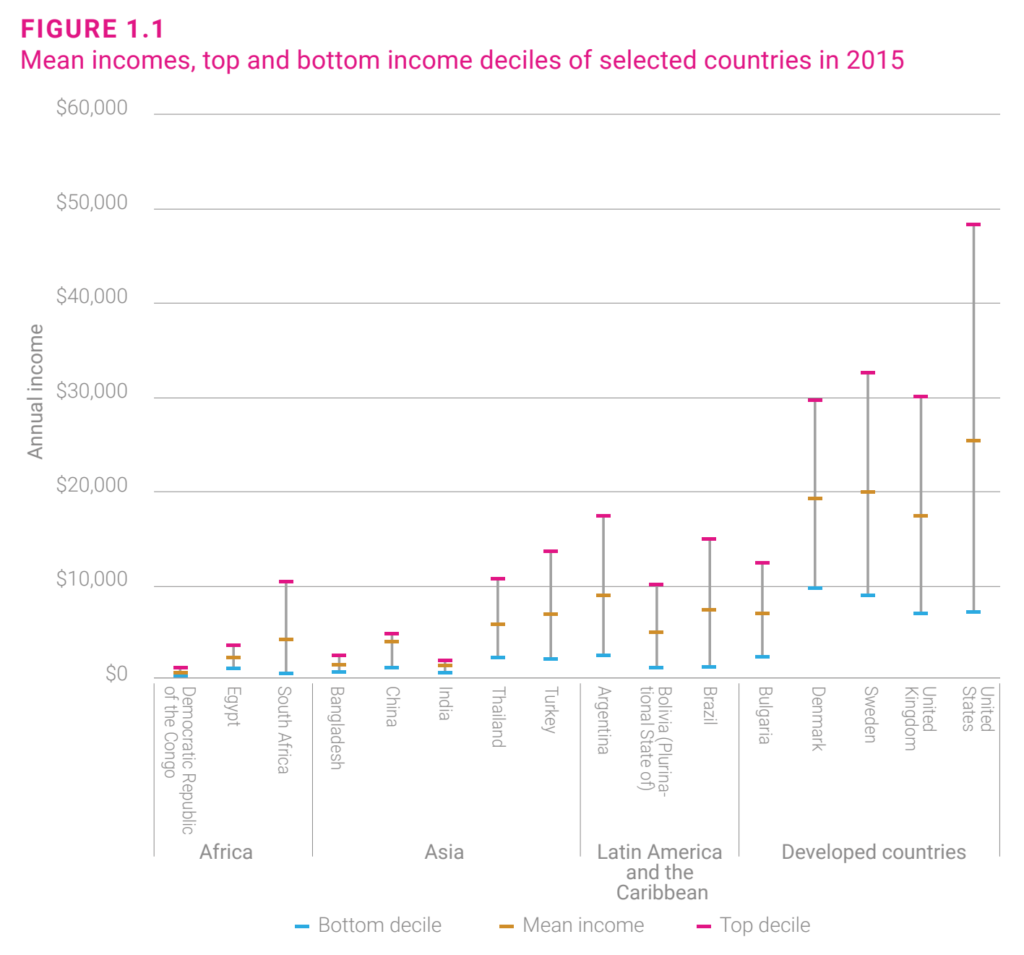

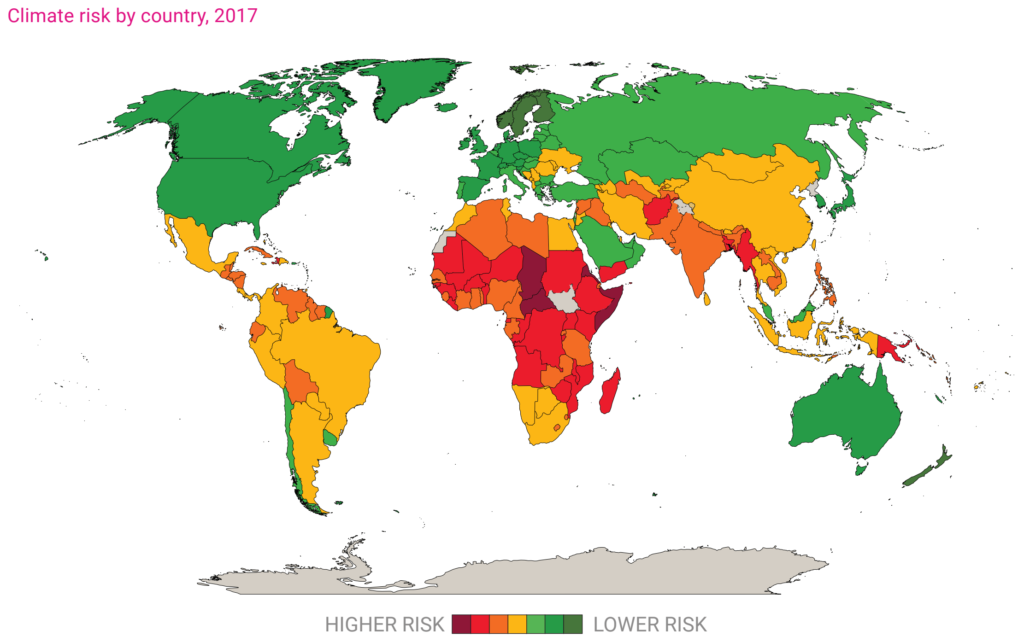

11 February 2020 (UNDESA) – The World Social Report 2020 examines the impact of four such megatrends on inequality: technological innovation, climate change, urbanization and international migration. Technological change can be an engine of economic growth, offering new possibilities in health care, education, communication and productivity. But it can also exacerbate wage inequality and displace workers. The accelerating winds of climate change are being unleashed around the world, but the poorest countries and groups are suffering most, especially those trying to eke out a living in rural areas. Urbanization offers unmatched opportunities, yet cities find abject poverty and opulent wealth in close proximity, making gaping and increasing levels of inequality all the more glaring. International migration allows millions of people to seek new opportunities and can help reduce global disparities, but only if it occurs under orderly and safe conditions.

Whether these mega-trends are harnessed to encourage a more equitable and sustainable world, or allowed to exacerbate disparities and divisions, will largely determine the shape of our common future.