Oceans losing oxygen at unprecedented rate, experts warn

By Fiona Harvey

7 December 2019

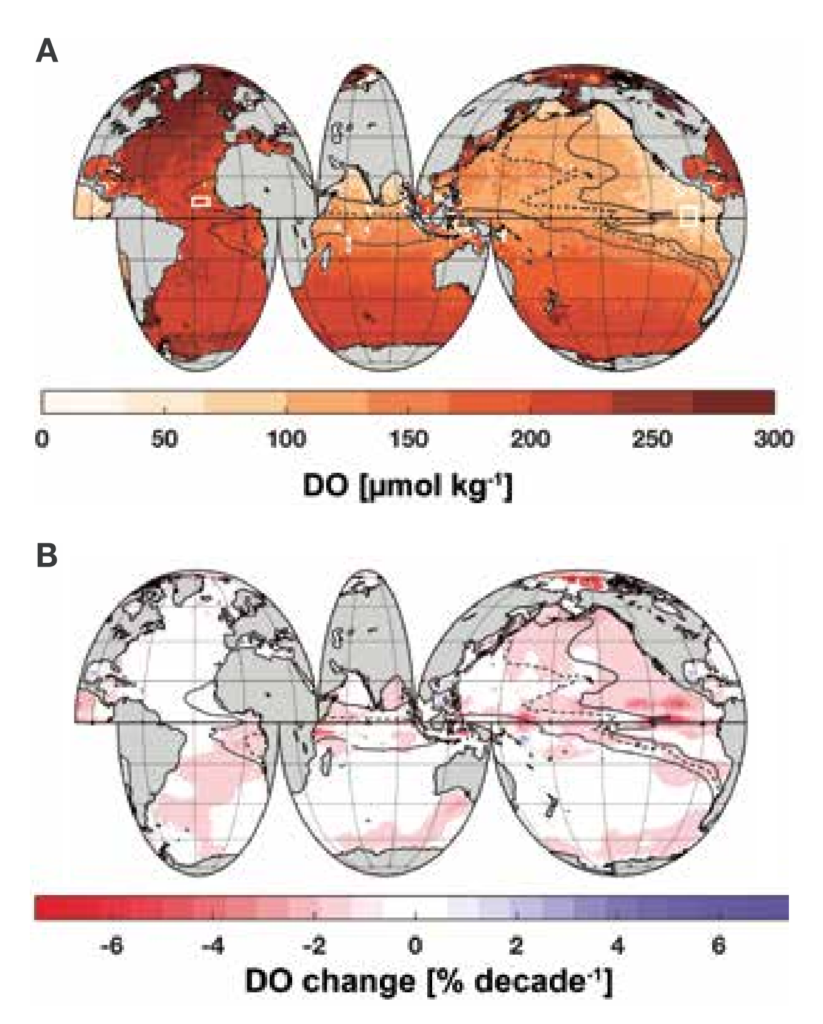

MADRID (The Guardian) – Oxygen in the oceans is being lost at an unprecedented rate, with “dead zones” proliferating and hundreds more areas showing oxygen dangerously depleted, as a result of the climate emergency and intensive farming, experts have warned.

Sharks, tuna, marlin and other large fish species were at particular risk, scientists said, with many vital ecosystems in danger of collapse. Dead zones – where oxygen is effectively absent – have quadrupled in extent in the last half-century, and there are also at least 700 areas where oxygen is at dangerously low levels, up from 45 when research was undertaken in the 1960s.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature presented the findings on Saturday at the UN climate conference in Madrid, where governments are halfway through tense negotiations aimed at tackling the climate crisis. [Ocean deoxygenation : everyone’s problem]

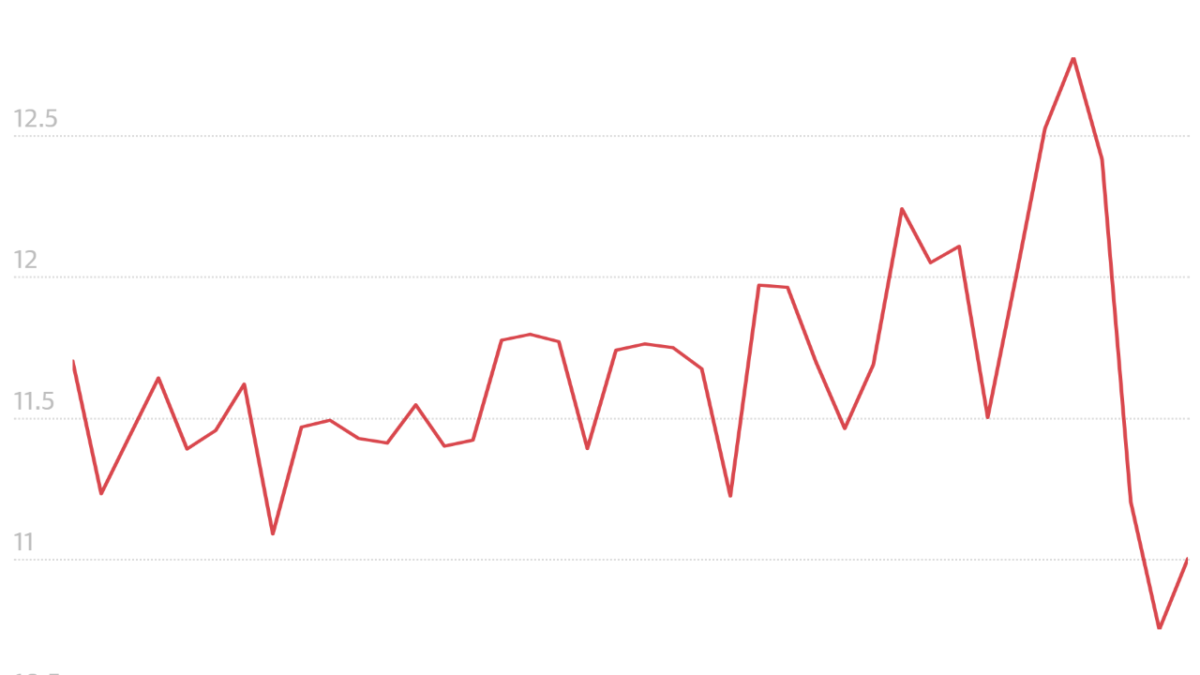

Prior to 1960, there were about 45 systems with reports of eutrophication-related hypoxia. During the 1960s, another 60 systems were added. The 1970s saw estuarine and coastal ecosystems around the world becoming over-enriched with organic matter from expanding eutrophication and the number of oxygen-depleted ecosystems jumped from about 100 to 180. In the 1980s many more systems reported hypoxia for the first time bringing the total to about 330. More hypoxic areas were reported in the 1990s than any other decade and the total rose to about 500 systems. By the end of the 20th century the total was about 500 and hypoxia had become a major, worldwide environmental problem. At the end of the first decade of the 21st century another 140 sites reported hypoxia, bringing the total to about 640. This total of 640 does not include about 65 sites that Conley et al. (2011) identified from the Baltic region. When these are added the total number of dead zones jumps to about 700. An additional 230 coastal sites were identified as areas of concern that currently exhibit signs of eutrophication and are at risk of developing hypoxia.

Ocean deoxygenation : everyone’s problem , p. 88

Grethel Aguilar, the acting director general of the IUCN, said the health of the oceans should be a key consideration for the talks. “As the warming ocean loses oxygen, the delicate balance of marine life is thrown into disarray,” she said. “The potentially dire effects on fisheries and vulnerable coastal communities mean that the decisions made at the conference are even more crucial.”

All fish need dissolved oxygen, but the biggest species are particularly vulnerable to depleted oxygen levels because they need much more to survive. Evidence shows that depleted levels are forcing them to move towards the surface and to shallow areas of sea, where they are more vulnerable to fishing. […]

The problem of dead zones has been known about for decades, but little has been done to tackle it. Farmers rarely bear the brunt of the damage, which mainly affects fishing fleets and coastal areas. Two years ago, the meat industry in the US was found to be responsible for a massive dead zone measuring more than 8,000 sq miles in the Gulf of Mexico.

This year’s UN climate conference, known as COP25, was originally billed as the “Blue COP”, with a spotlight on the oceans for the first time in the history of the negotiations. The focus was chosen because of the original location in Chile, a country with more than 4,000km of coastline and a strong reliance on the marine economy.

But the move to Madrid, forced by political unrest in Santiago, has meant many of the planned events have been curtailed. Scientists and activists gathered in landlocked Madrid are trying to highlight the issues by demonstrating how vital the seas are in protecting us from climate chaos – as they absorb so much of the excess carbon dioxide, and excess heat, in the atmosphere – and how much they are at risk from its impacts. [more]