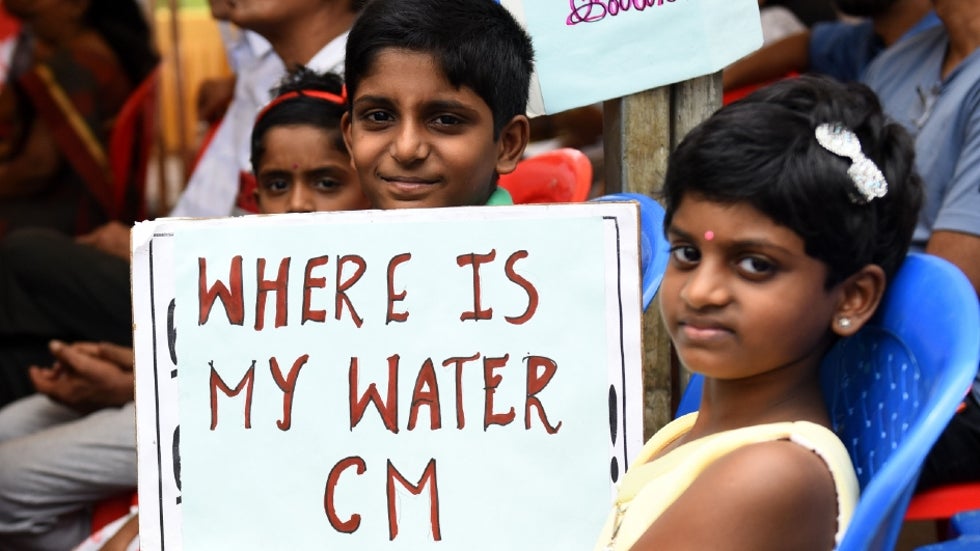

Thefts, fights, and murder: Water scarcity is making Chennai an angry city – “To see water scarcity leading to violence amongst neighbours is truly distressing. This is not the Chennai I know.”

By Karthikeyan Hemalatha

27 August 2019

(The Weather Channel India) – In her 71 years, R Mangayarkarasi has seen a lot change in Chennai. She was there in the 1950s, when the Adyar River was brimming with water. In the 1990s she witnessed encroachments swallow up the lake that gave ‘Lake View Road’ its name. During the unforgiving droughts of the early 2000s, she saw big, black Sintex tanks mushrooming at street corners where the City corporation would fill water once in two-three days. “Standing in line with our ‘kodams’ (plastic drums to carry water) was a good time to catch up with our neighbours,” she recalls. Even back then, the city’s water problems were seemingly unending. But it didn’t bother Mangayarkarasi and other citizens all that much.

What she has never seen before today, is the break-down of the community ethos she enjoyed growing up. “To see water scarcity leading to violence amongst neighbours is truly distressing. This is not the Chennai I know,” she laments.

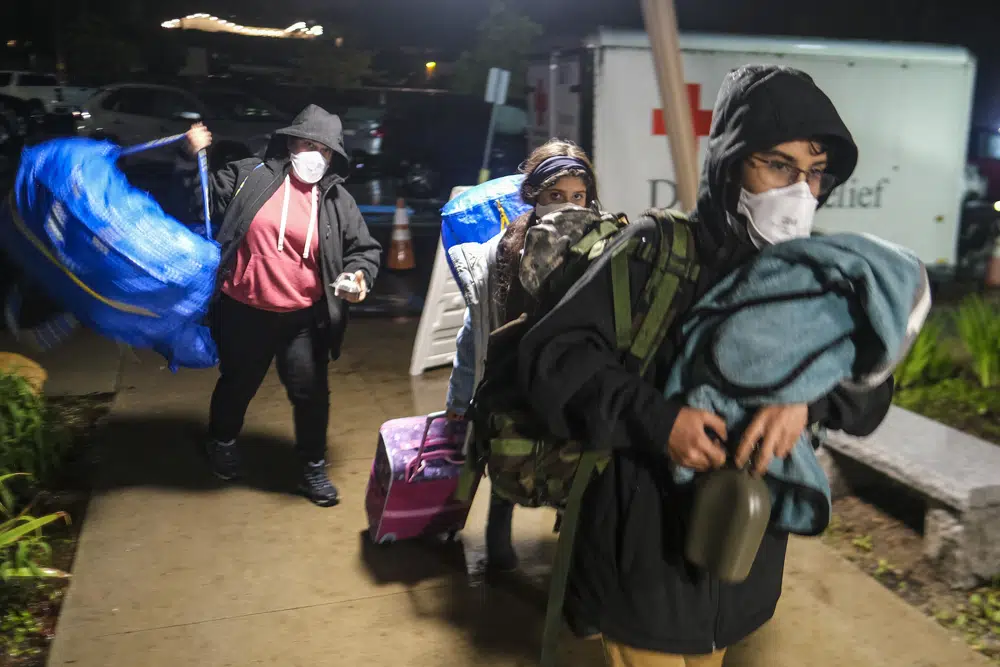

In June this year, just as the country began to slowly cool down with the delayed onset of the southwest monsoon, Tamil Nadu was facing one of its worst water crises. Soon, the capital city Chennai became the poster boy for the state’s drought. And soon after that, it was being likened to the Cape Town water crisis of 2017-18 and making headlines in the international media. But even as satellite images of the city’s near-empty reservoirs were doing the rounds, there was a rise in disputes, and even violent clashes, triggered by the lack of water.

On June 13 – during the period when the city was at its peak of the water crisis, a 28-year-old woman was stabbed by her neighbour over a water dispute. The attacker, Adimoola Ramakrishnan, wanted to switch on a motor while the victim’s husband Mohan insisted that the tank was empty and the motor should not be switched on. A fight ensued, following which Ramakrishnan went to his house to get a knife. He came back and stabbed Subhashini, Mohan’s wife. The local police has filed a case against Ramakrishnan.

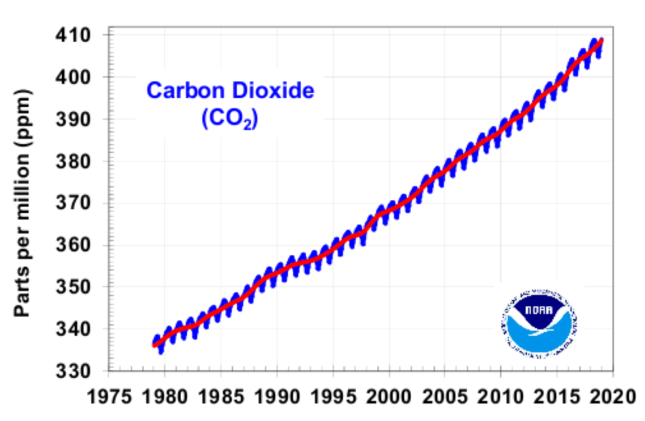

For many Chennaiites, such violence would have been unthinkable a few decades ago. While some experts blamed it on bad urban planning or poor reservoir management, others blamed climate change. For the layman, the crisis has meant standing in long queues, braving the scorching sun, irritated neighbours and rude water tanker operators.

“People get up as early as 3 am in the morning to pump water. Others wait in long queues and pay exorbitant prices for a water tanker. But when someone gets less water than his/her neighbour, frustration and anger seeps in, leading to clashes,” says Chandra Mohan, a social activist from Arappor Iyakkam.

It also drives some to crime, as G Gautham [name changed], who lives in a posh locality of RA Puram, found out. Gautham used influence to get Metro water tankers to prioritise his house for water delivery. But there was something amiss. “The water that used to last us two weeks started getting over in two or three days. I then realised that people were stealing water from the tap near our gate,” he said. Gautham was forced to cut the water connection to the tap, and install CCTV cameras as a security measure. “I didn’t think this could happen in Chennai,” he says. [more]

Thefts, Fights and Murder: Water Scarcity is Making Chennai an Angry City