Hardy scientists trek to Venezuela’s last glacier amid chaos – “More than 50 million people in South America rely on water provision from the Andes”

By Christina Larson and Federica Narancio

24 September 2019

MERIDA, Venezuela (AP) – Blackouts shut off the refrigerators where the scientists keep their lab samples. Gas shortages mean they sometimes have to work from home. They even reuse sheets of paper to record field data because fresh supplies are so scarce.

As their country falls apart, a hardy team of scientists in Venezuela is determined to transcend the political and economic turmoil to record what happens as the country’s last glacier vanishes.

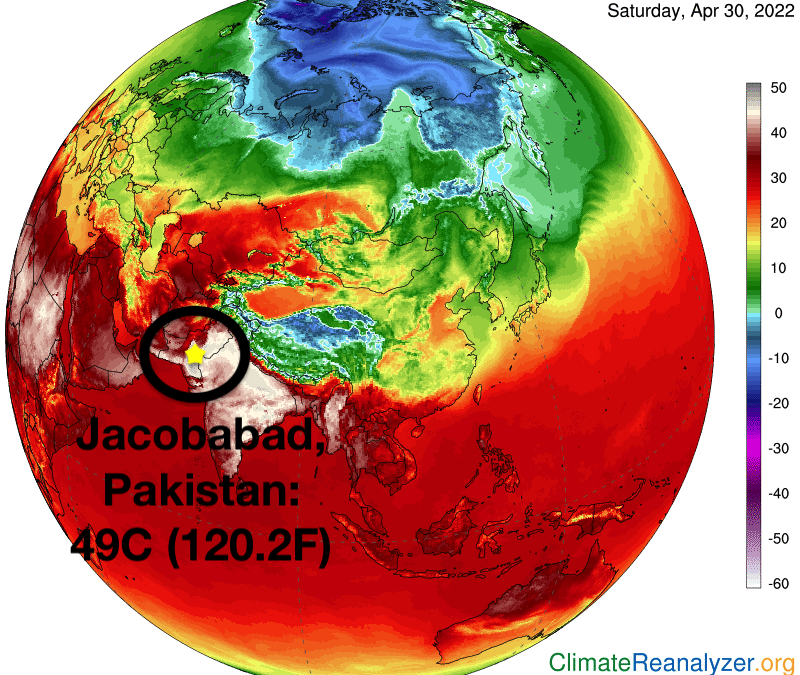

Temperatures are warming faster at the Earth’s higher elevations than in lowlands, and scientists predict that the glacier — an ice sheet in the Andes Mountains — could be gone within two decades.

“If we left and came back in 20 years, we would have missed it,” says Luis Daniel Llambí, a mountain ecologist at the University of the Andes in Mérida.

Scientists say Venezuela will be the first country in South America to lose all its glaciers. […]

“Practically all of the high-mountain tropical glaciers are in the Andes. There’s still a little bit on Mount Kilimanjaro,” says Robert Hofstede, a tropical ecologist in Ecuador who advises international agencies such as the World Bank and United Nations. […]

“Every week, someone asks me why I haven’t left,” says Alejandra Melfo, a team member who is a physicist at the University of the Andes.

Not now, she tells anyone who asks.

“Climate change is real and has to be documented,” she says. “We have to be there.” […]

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the Andean glaciers in maintaining regional water cycles.

“More than 50 million people in South America rely on water provision from the Andes,” says Francisco Cuesta, a tropical ecologist at the University of the Americas in Quito, Ecuador, who marvels at the dogged work the team is doing under such punishing conditions.

“To me, it’s incredible that they are still doing research there,” Cuesta says. […]

“Our university is in Mérida, which has long been called ‘the city of eternal snow,‘” he reflects. “We are discovering that ‘eternity’ is not forever, and that’s what we have to get used to in a world with climate change.” [more]

Hardy scientists trek to Venezuela’s last glacier amid chaos