Disaster strikes in Bolivia as agricultural fires lay waste to unique forests – “Fire is a monster and is threatening us. Everything is ashes and fear.”

By Carolina Méndez, Isabel Mercado

6 September 2019

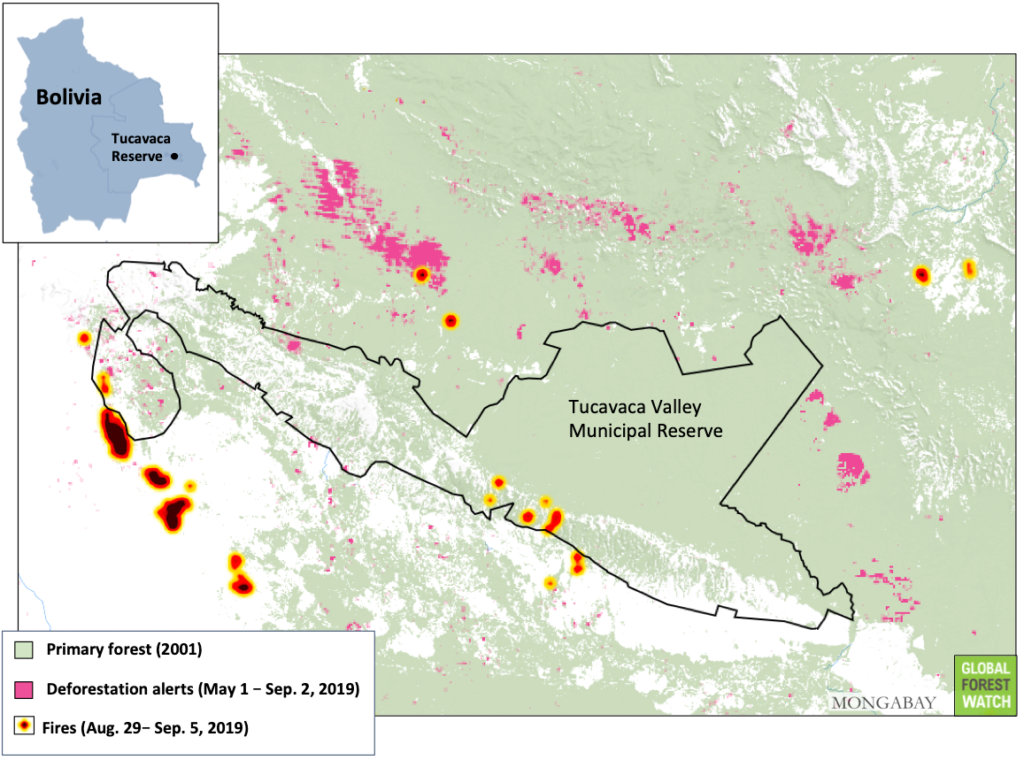

(Mongabay) – “Fire is a monster and is threatening us. Everything is ashes and fear,” says Iván Quezada, the mayor of Roboré, a town in eastern Bolivia. Last week, fires consumed more than 450,000 hectares (1.11 million acres) of forest; if added to the amount of forest destroyed since the fires in Bolivia began this year, that figure would border on a million hectares (2.5 million acres), according to official sources.

Every year at this time, the chaqueos, burning events to prepare the land for planting crops or raising cattle, are carried out in the Chiquitania region of eastern Bolivia, often generating fires that burn out of control. However, this year is worse. Boosted by a controversial governmental decree that promotes the expansion of the agricultural frontier and allows “controlled burning” in forests, the chaqueos have triggered a crisis for the area’s unique dry forests and savannas.

What is happening is not an accident. Five years ago, the vice president challenged agribusinesses to expand the agricultural frontier by one million hectares per year. Now it has reached that figure, not of productive agricultural land but of land devastated by the flames.

Pablo Solón, former Bolivian ambassador to the U.N.

On 9 July 2019, President Evo Morales approved the amendment of Supreme Decree 26075 to expand land demarcated for livestock production and the agribusiness sector to include Permanent Forest Production Lands in the regions of Beni and Santa Cruz. The decree authorizes the clearing of forest for agricultural activities in private- and community-held areas under a system of sustainable management. According to current regulations, this system allows controlled burning.

“We have the duty and mission to boost Bolivia’s economic growth, not only based on non-renewable natural resources but also based on agriculture,” Morales said. He added via Twitter that the government is planning on expanding agricultural production and infrastructure to boost beef exports to China.

A crisis in Santa Cruz

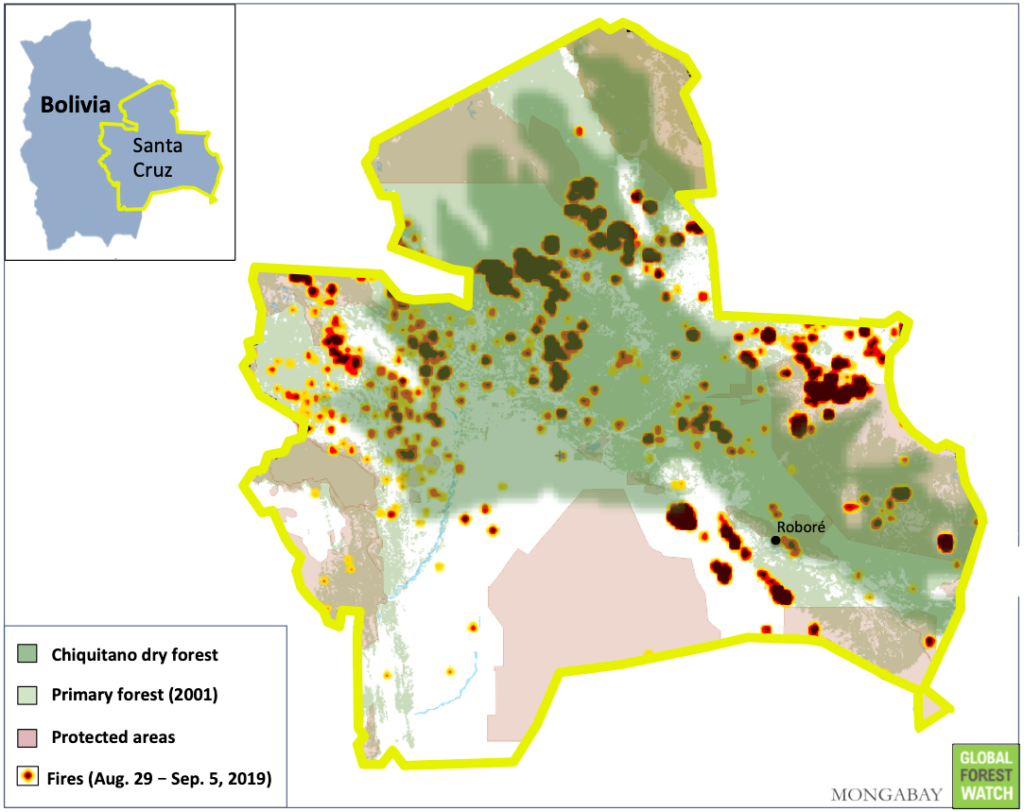

Bolivia’s Santa Cruz region is rich in forest cover. But the lack of rain in the last three months has turned the dry forest into combustible fuel, with eight nearby communities directly affected by fires so far.

One of these is the town of Roboré, where the air is thick with smoke. The situation is more somber in surrounding communities, however. Families depend on water transported from the mountains via hoses. But these hoses these have been burned, cutting off community access to drinking water. Moreover, residents report that any water that reaches them is full of ashes, which causes digestive and respiratory problems, infections and conjunctivitis. Community activities, including school, have been suspended. Local authorities have requested the declaration of a state of emergency, but the government says it is not necessary.

Firefighters sent by the Santa Cruz police department to battle the blazes face difficulties on the ground. For one, there are no trails to access the fire areas. Also, because water delivery systems can’t cross roads in the region, firefighters are forced to carry water in backpacks. Ultimately, this means firefighting is slower than the rate at which the fires are spreading; as fires are being put out on one side of the road, more are ignited on the other.

Along with the regulation changes and seasonal burning practices, windy conditions are contributing to the inferno, helping spread the fires over an ever-greater area. With strong winds forecast in the near future, many are worried things are just going to get worse.

Skyrocketing deforestation

Bolivia is no stranger to fire and deforestation. According to numbers from the University of Maryland (UMD), which has been collating satellite data on the world’s forests since the beginning of the century, the country lost 7.5 percent of its tree cover between 2001 and 2018. The record-holding year during this period was 2016, when around 471,000 hectares (1.16 million acres) of tree cover were lost.

But preliminary data for 2019 indicate this year could dramatically unseat 2016. According to the Forest and Land Audit and Social Control Authority (ABT), fires have consumed more than 953,000 hectares (2.35 million acres) of Bolivian forest so far. If these data hold true, this means that deforestation in 2019 will be more than double that of 2016 — and more than three times the 300,000 hectares (741,000 acres) lost in 2018.

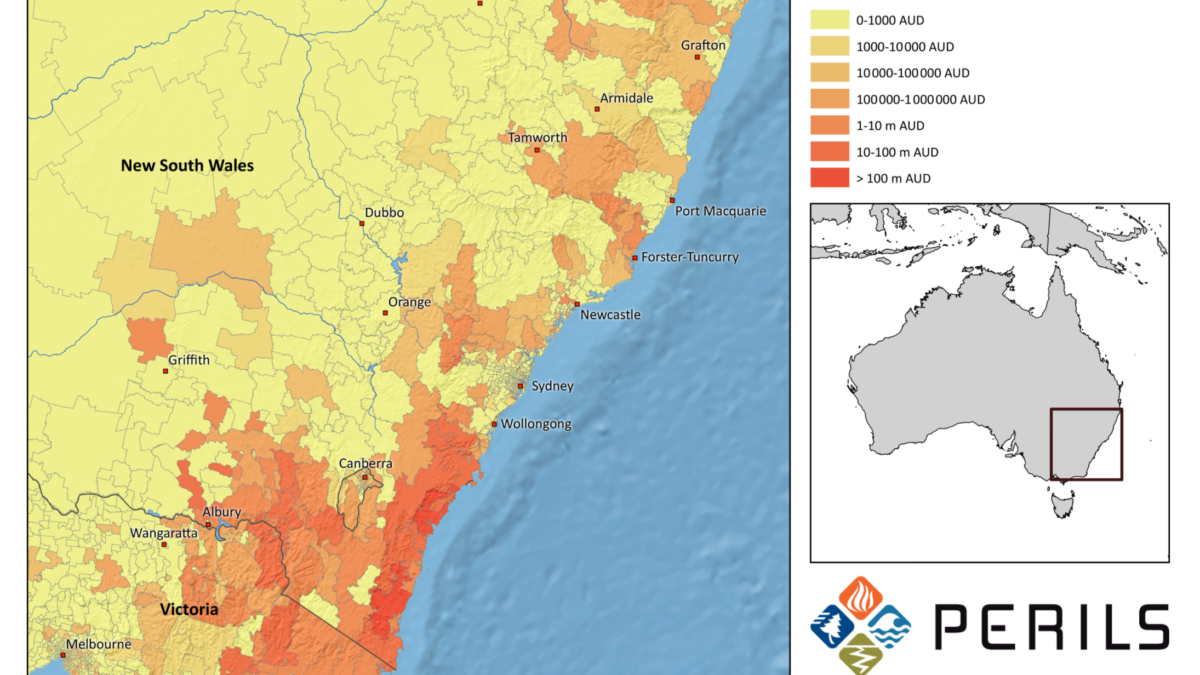

The lion’s share of Bolivia’s deforestation is happening in the Santa Cruz region, which comprises vast tracts of both the rainforest of the Amazon and the dry forests of the Gran Chaco. Satellite data show that Santa Cruz lost a full 10 percent of its tree cover in less than two decades. Here, too, preliminary numbers from UMD indicate 2019 may be a banner year for forest loss, with tree cover loss alerts spiking in late August to levels more than double the average of previous years. Most of these alerts are occurring in areas with high fire activity, according to data from NASA that show Santa Cruz fire activity in August was around three times higher than in years past.

“If we take 2012 as the base year, when 128,043 hectares [316,401 acres] were deforested [in Santa Cruz], this year’s deforestation would be more than seven times greater; and if we take only the deforestation of Chiquitania, it would be three times greater,” said Pablo Solón, former Bolivian ambassador to the U.N.

Santa Cruz’s forests are being carved away to free up more land for soy plantations, cattle ranches, illicit coca-growing operations, and biofuel crops, as well as for the expansion of towns and smallholder farms. According to officials, the region most affected by the recent fires is a major soybean and livestock production area.

“What is happening is not an accident. Five years ago, the vice president challenged agribusinesses to expand the agricultural frontier by one million hectares per year,” Solon said. “Now it has reached that figure, not of productive agricultural land but of land devastated by the flames.” [more]

Disaster strikes in Bolivia as fires lay waste to unique forests