Dangerous new hot zones are spreading around the world

By Chris Mooney and John Muyskens

11 September 2019

LA CORONILLA, Uruguay (The Washington Post) – The day the yellow clams turned black is seared in Ramón Agüero’s memory.

It was the summer of 1994. A few days earlier, he had collected a generous haul, 20 buckets of the thin-shelled, cold-water clams, which burrow a foot deep into the sand along a 13-mile stretch of beach near Barra del Chuy, just south of the Brazilian border. Agüero had been digging up these clams since childhood, a livelihood passed on for generations along these shores.

But on this day, Agüero returned to find a disastrous sight: the beach covered in dead clams.

“Kilometer after kilometer, as far as our eyes could see. All of them dead, rotten, opened up,” remembered Agüero, now 70. “They were all black, and had a fetid odor.”

He wept at the sight.

The clam die-off was an alarming marker of a new climate era, an early sign of this coastline’s transformation. Scientists now suspect the event was linked to a gigantic blob of warm water extending from the Uruguayan coast far into the South Atlantic, a blob that has only gotten warmer in the years since.

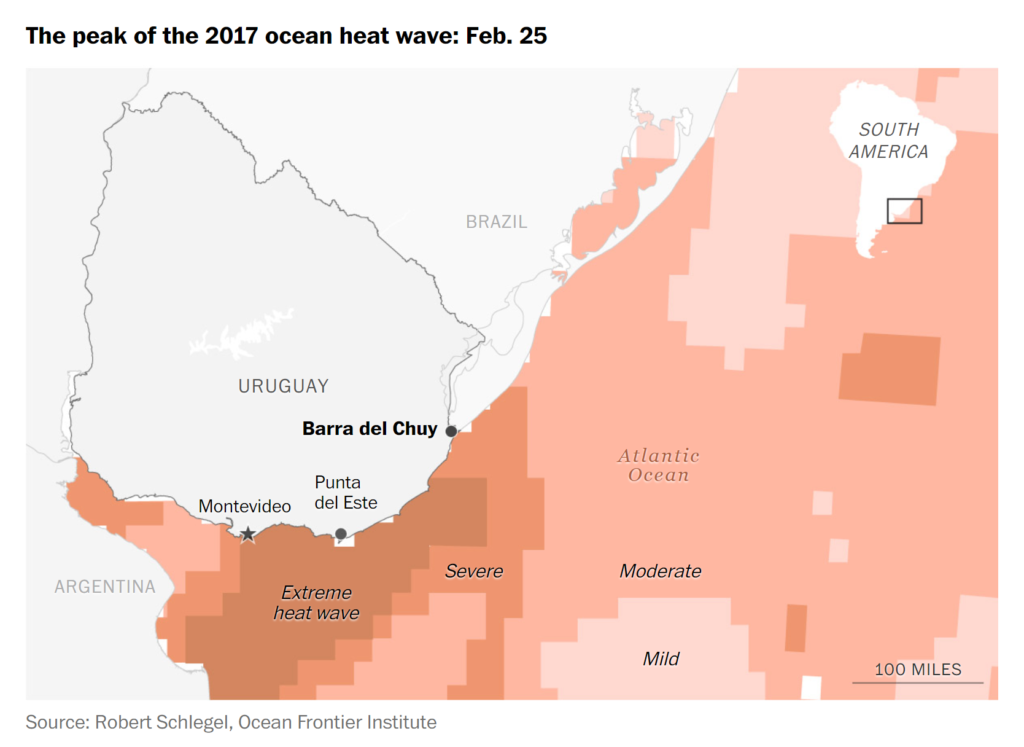

The mysterious blob covers 130,000 square miles of ocean, an area nearly twice as big as this small country. And it has been heating up extremely rapidly — by over 2 degrees Celsius — or 2C — over the past century, double the global average. At its center, it’s grown even hotter, warming by as much as 3 degrees Celsius, according to one analysis.

The entire global ocean is warming, but some parts are changing much faster than others — and the hot spot off Uruguay is one of the fastest. It was first identified by scientists in 2012, but it is still poorly understood and has received virtually no public attention.

What researchers do know is that the hot zone here has driven mass die-offs of clams, dangerous ocean heat waves and algal blooms, and wide-ranging shifts in Uruguay’s fish catch.

The South Atlantic blob is part of a global trend: Around the planet, enormous ocean currents are traveling to new locations. As these currents relocate, waters are growing warmer. Scientists have found similar hot spots along the western stretches of four other oceans — the North Atlantic, the North Pacific, the South Pacific, and the Indian.

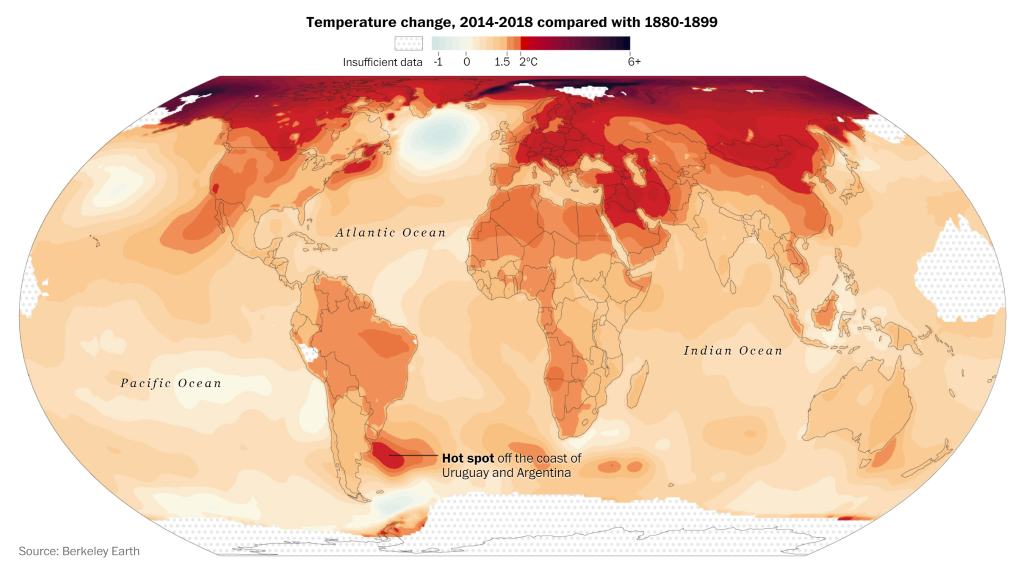

A Washington Post analysis of multiple temperature data sets found numerous locations around the globe that have warmed by at least 2 degrees Celsius over the past century. That’s a number that scientists and policymakers have identified as a red line if the planet is to avoid catastrophic and irreversible consequences. But in regions large and small, that point has already been reached.

Some entire countries, including Switzerland and Kazakhstan, have warmed by 2C. Austria has said the same about its famed Alps. […]

These hot spots are the scenes of a critical acceleration, places where geophysical processes are amplifying the general warming trend. They unveil which parts of the Earth will suffer the largest changes. [more]