India is running out of water – “If nothing changes, and fast, things will get much worse, with severe water scarcity on the horizon for hundreds of millions”

By Bill Spindle and Gareth Phillips

19 August 2019

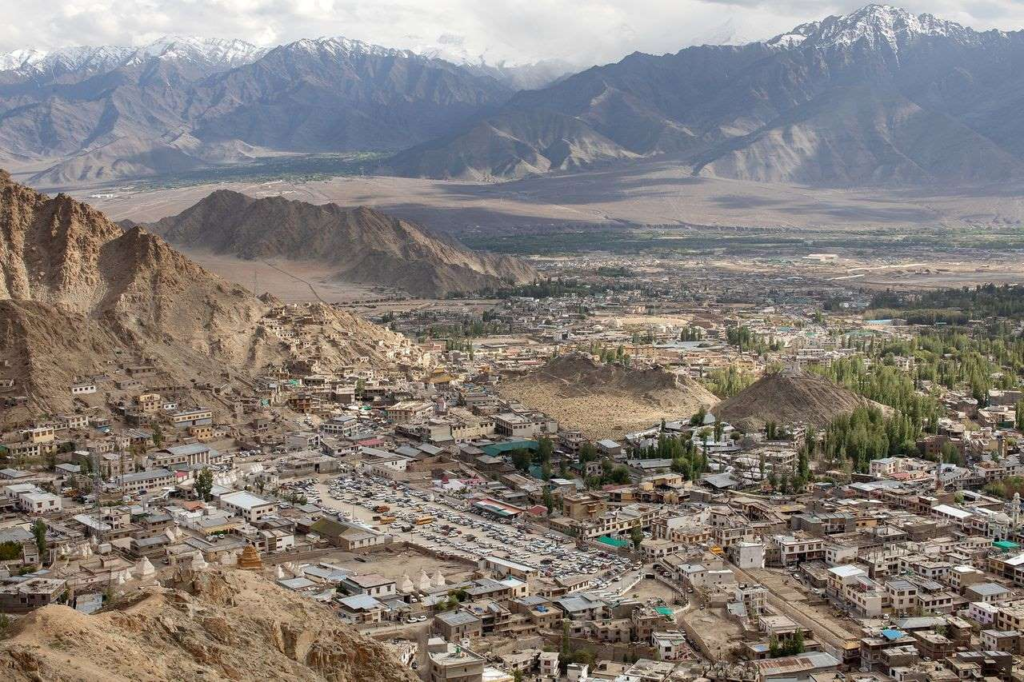

LEH, India (The Wall Street Journal) – The Ladakh region of northern India is one of the world’s highest, driest inhabited places. For centuries, meltwater from winter snows in the Himalayan mountains sustained the tiny villages dotting this remote land.

Now, like many other places in India, parts of Ladakh are running short of water. A tourism boom has sent the summer population soaring, and the region’s traditional system of conserving water is breaking down.

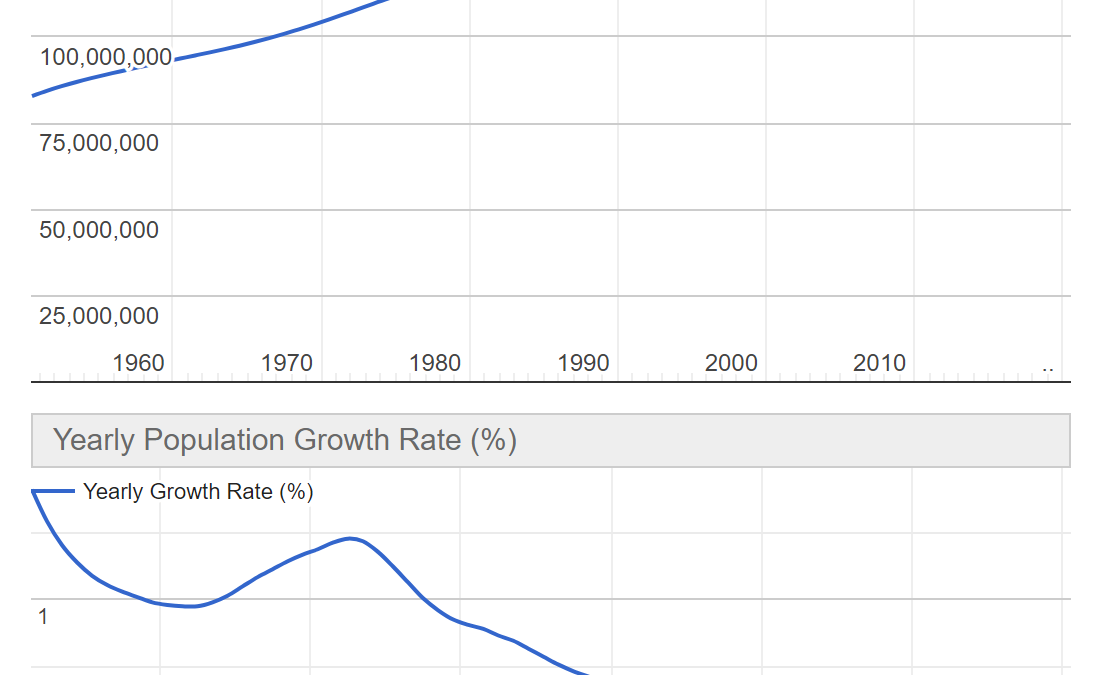

Water crises are unfolding all across India, a product of population growth, modernization, climate change, mismanagement and the breakdown of traditional systems of distributing resources. India is running out of water in more places, in more different ways, putting more people at risk, than perhaps any other country.

Nearly all of India’s biggest cities, including New Delhi, the nation’s capital, are rapidly depleting their groundwater reserves, and 40% of India’s people could lack drinking water by the end of the next decade, according to a 2018 report by NITI Aayog, a government-policy think tank.

In Ladakh, making matters worse, the winters snows were scarce last year. In the fields above the city of Leh, tensions ran high.

Until now, it’s been relatively easy to increase supply without thinking too much about demand. But parts of India are beginning to hit the natural limits of water supply. Unless there is a reduction in the rate at which those resources are being used, they are eventually going to run out.

Mervyn Piesse, manager of the global food and water crises research program at Future Directions International, a research institute based in Nedlands, Australia.

India is the 13th most water-stressed country in the world, but its population is triple the combined population of the other 16 countries facing extremely high water stress, according to the World Resources Institute, a nonprofit group with offices around the world that tracks water use and other global environmental and resource issues.

Water resources in India have been mismanaged for decades. Critical groundwater resources, which account for 40 percent of India’s water supply, are being depleted at unsustainable rates, the NITI Aayog report said. Droughts are becoming more frequent, creating severe problems for India’s rain-dependent farmers.

By 2030, water demand in India is projected to be twice the available supply, according to the report. “If nothing changes, and fast, things will get much worse…with severe water scarcity on the horizon for hundreds of millions,” the report said.

In the southern city of Chennai, drinking water reserves almost completely dried up this year. Although a 200-day streak with no rain ended recently, the first month of the annual monsoon brought one-third less rain than the 50-year average, which makes it the driest June in five years, according to the India Meteorological Department.

Two of Chennai’s four reservoirs went dry, and the other two nearly did. Millions of residents of the city, India’s fifth largest, with a population of about 10 million, have to get their drinking water from trucks—either sporadically from government vehicles or by purchasing it from private companies.

In the agricultural heartland of India’s northern plains, where almost one-third of the country’s food is grown, farmers generally pay little or nothing for the groundwater they use or the energy needed to pump as much as they desire. That has led them to plant water-intensive crops, creating shortages, especially during lapses in the annual monsoons, that endanger the country’s food supply. […]

“Until now, it’s been relatively easy to increase supply without thinking too much about demand. But parts of India are beginning to hit the natural limits of water supply,” said Mervyn Piesse, manager of the global food and water crises research program at Future Directions International, a research institute based in Nedlands, Australia. “Unless there is a reduction in the rate at which those resources are being used, they are eventually going to run out.” […]

A warming climate is making water supplies more unpredictable throughout the Himalayan region, upon whose watershed some two billion people ultimately depend. A recent study by a nongovernmental organization that focuses on regional developmental issues, called the Hindu Kush Monitoring and Assessment Program, warned that glaciers feeding rivers in the Himalayan region could start disappearing after 2050. [more]