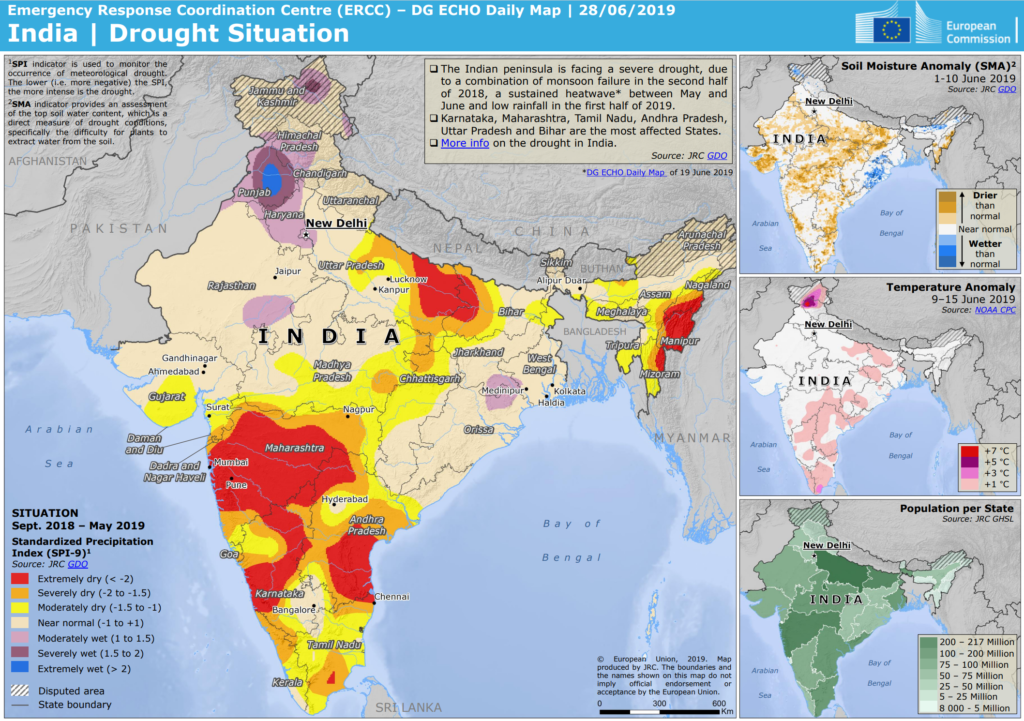

Why India’s Chennai has run out of water

By Nityanand Jayaraman

1 July 2019

(BBC News) – As I write this, it has rained in Chennai – the first real welcome shower, but one that lasted only 30 minutes. But, still, that has been enough to flood the streets and stall traffic. The irony is that Chennai’s vulnerability to floods and its water scarcity have common roots. Blinded by a hurry to grow, the city has paved over the very infrastructures that nurtured water.

Between 1980 and 2010, heavy construction in the city meant its area under buildings increased from 47 sq km to 402 sq km. Meanwhile, areas under wetlands declined from 186 to 71.5 sq km.

The city is no stranger to drought or heavy rains. The north-east monsoon, which brings most of the water to this region in October and November, is unpredictable. Some years it pours, and in other years, it just fails to show up.

The Manali marshlands were drained in the 1960s for Tamil Nadu’s largest petrochemical refinery. Electricity for the city comes from a cluster of power plants built on the Ennore Creek, a tidal wetland that has been converted into a dump for coal-ash.

Any settlement in the region ought to have been designed for both eventualities – with growth limited not by availability of land but of water. Early agrarian settlements in Chennai and its surrounding districts did exactly this.

Shallow, spacious tanks – called erys in Tamil- were carved out on the region’s flat coastal plains by erecting bunds with the same earth that was scooped out to deepen them. Essentially, the infrastructure for water to stay and flow was created first; the settlements came later. […]

The city has pursued its aspirations to become an economic hub by promoting itself as a major IT and automotive manufacturing centre. In addition to attracting new settlers to Chennai and vastly increasing the pressure on scant resources, these industries have dealt death blows to the region’s water infrastructure.

Land-use planning today is a far cry from the simple principles that prevailed in medieval Tamil Nadu.

Wetlands were off-limits for construction, and only low-density buildings were permitted on lands immediately upstream of tanks. The reason: These lands have to soak up the rainwater before letting it to run to the reservoir.

It is this sub-surface water that will flow to the lake as the levels go down with use and time. Unmindful of such common sense, the IT Corridor (a road which houses a large number of IT companies in the city) was built almost entirely on Chennai’s precious Pallikaranai marshlands.

And the area immediately upstream of Chembarambakkam – the city’s largest drinking water tank – has now been converted into an automotive special economic zone (SEZ).

Other water bodies have been treated with similar disdain.

The Perungudi garbage dump spreads out through the middle of the Pallikaranai marshlands.

The Manali marshlands were drained in the 1960s for Tamil Nadu’s largest petrochemical refinery. Electricity for the city comes from a cluster of power plants built on the Ennore Creek, a tidal wetland that has been converted into a dump for coal-ash.

The Pallavaram Big Tank, which is perhaps more than 1,000 years old, has over the last two decades been bisected by a high-speed road with the remainder serving as a garbage dump for the locality.

In Chennai, the water utility supplies are barely a fourth of the total water demand. The remainder is supplied by a powerful network of commercial water suppliers who are sucking resources in the region dry.

Along the periphery of Chennai, and far into the hinterland, the land is dotted with communities whose water and livelihoods have been forcibly taken to feed the city. The water crises in these localities desiccated by the city never make it to the news. [more]