Where lions once ruled, they are now quietly disappearing – Lion population has declined by 50 percent in 25 years

By Olivia Prentzel

18 July 2019

(National Geographic) – For every lion in the wild, there are 14 African elephants, and there are 15 Western lowland gorillas. There are more rhinos than lions, too.

The iconic species has disappeared from 94 percent of its historic range, which once included almost the entire African continent but is now limited to less than 660,000 square miles. With fewer than an estimated 25,000 in Africa, lions are listed as vulnerable to extinction by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, which determines the conservation status of species.

To put things in perspective, the nonprofit Wildlife Conservation Network (WCN) notes that lion numbers have dropped by half since The Lion King premiered in theaters in 1994. (The Walt Disney Company is majority owner of National Geographic Partners.) [cf. Lion (Panthera leo) populations are declining rapidly across Africa, except in intensively managed areas. –Des]]

“Lions are truly one of the world’s universal icons, and they are quietly slipping away,” says Paul Thomson, director of conservation programs for WCN. “Now is the time to stop the loss and bring lions back to landscapes across the continent.” […]

Africa’s revered predators face myriad threats that put their very existence at risk. The decrease in lions’ wild prey for the bushmeat trade forces lions into dangerous contact with humans and their livestock in search of food. But if the cats prey on cattle, they may be killed in retaliation—often by poison. And as human settlements grow, lions lose their habitat and see it fragmented, making it difficult for males to find new prides and mate. (Read more about how poison is a growing threat to Africa’s wildlife.)

Poaching, too, poses a threat. Skin, teeth, paws, and claws are used in traditional rituals and medicine, and there’s a growing market for lion parts in Asia as well.

Conservationists hope to halt the decline of the fragile species by supporting the coexistence of lions and humans across Africa. Part of the solution is offsetting the financial burden required to manage the protected areas, which are the backbone of conservation, as well as protecting lions in unprotected areas, says Amy Dickman, a National Geographic grantee and research fellow at the Oxford Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) and the co-author of a 2019 report called “State of the Lion.”

“If we want lions to exist in 50 years from now in any meaningful way, we need to adjust the costs and benefits so that far more of the benefits accrue at the local level and the costs are borne at the international level,” Dickman says. [more]

Where lions once ruled, they are now quietly disappearing

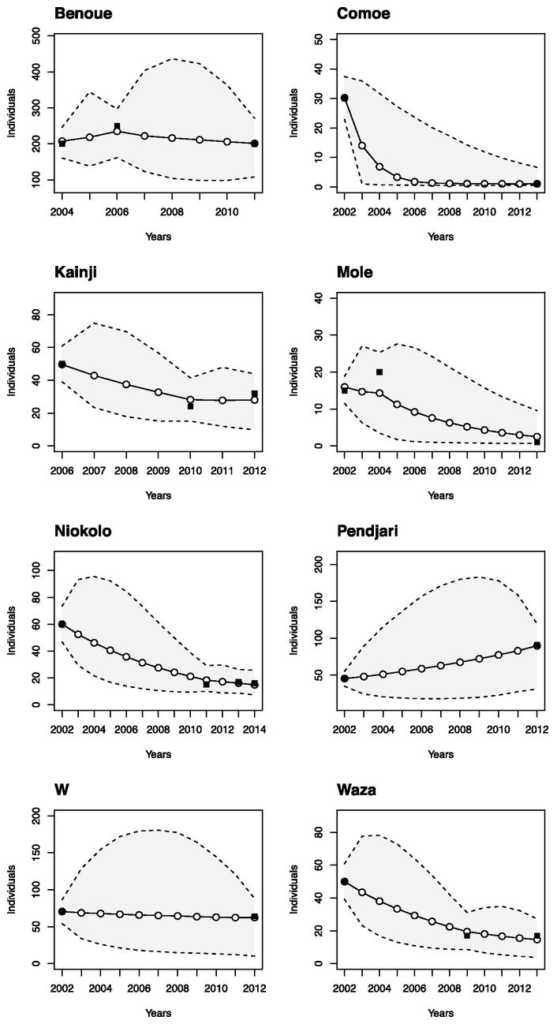

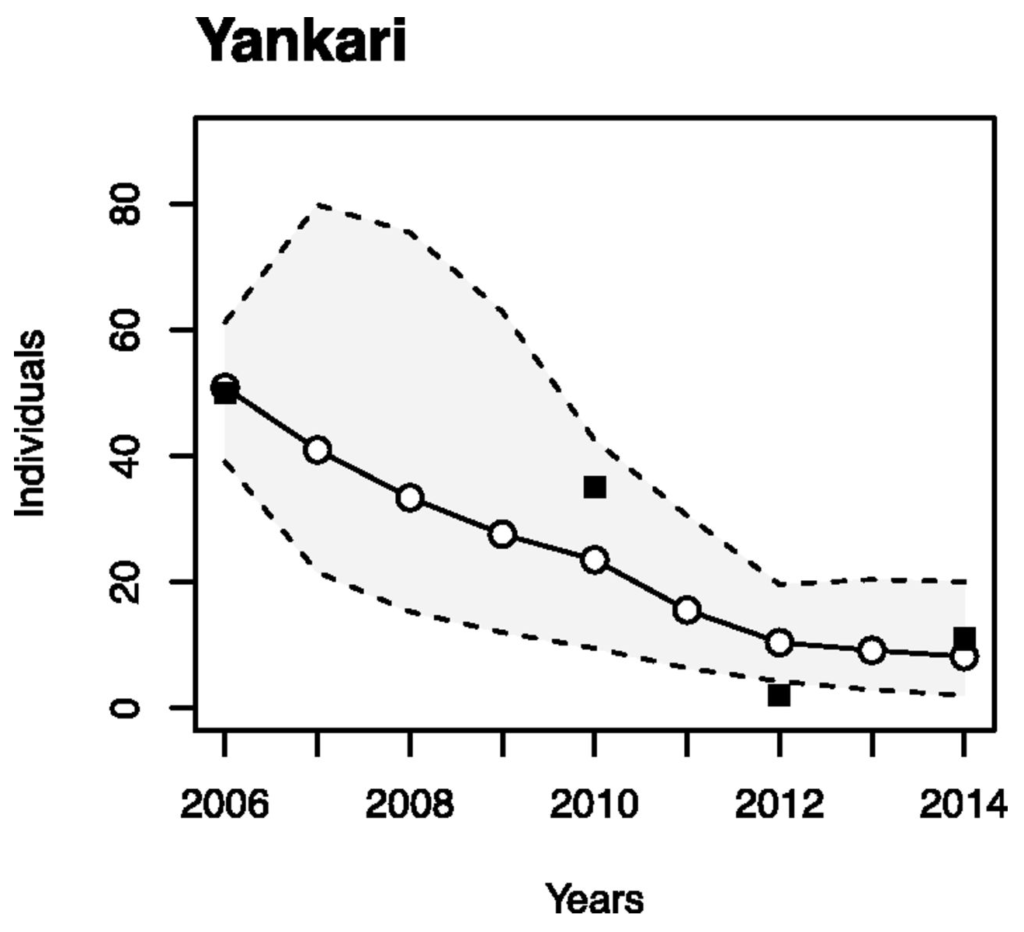

ABSTRACT: We compiled all credible repeated lion surveys and present time series data for 47 lion (Panthera leo) populations. We used a Bayesian state space model to estimate growth rate-λ for each population and summed these into three regional sets to provide conservation-relevant estimates of trends since 1990. We found a striking geographical pattern: African lion populations are declining everywhere, except in four southern countries (Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe). Population models indicate a 67% chance that lions in West and Central Africa decline by one-half, while estimating a 37% chance that lions in East Africa also decline by one-half over two decades. We recommend separate regional assessments of the lion in the World Conservation Union (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species: already recognized as critically endangered in West Africa, our analysis supports listing as regionally endangered in Central and East Africa and least concern in southern Africa. Almost all lion populations that historically exceeded ∼500 individuals are declining, but lion conservation is successful in southern Africa, in part because of the proliferation of reintroduced lions in small, fenced, intensively managed, and funded reserves. If management budgets for wild lands cannot keep pace with mounting levels of threat, the species may rely increasingly on these southern African areas and may no longer be a flagship species of the once vast natural ecosystems across the rest of the continent.

SIGNIFICANCE: At a regional scale, lion populations in West, Central, and East Africa are likely to suffer a projected 50% decline over the next two decades, whereas lion populations are only increasing in southern Africa. Many lion populations are either now gone or expected to disappear within the next few decades to the extent that the intensively managed populations in southern Africa may soon supersede the iconic savannah landscapes in East Africa as the most successful sites for lion conservation. The rapid disappearance of lions suggests a major trophic downgrading of African ecosystems with the lion no longer playing a pivotal role as apex predator.