Shifts to renewable energy can drive up energy poverty, study finds – “We don’t think of energy as a human right when it actually is”

By Cristina Rojas

12 July 2019

(PSU) – Efforts to shift away from fossil fuels and replace oil and coal with renewable energy sources can help reduce carbon emissions but do so at the expense of increased inequality, according to a new Portland State University study. [Data available here: Renewable energy injustice McGee and Greiner 2019.xlsx. –Des]

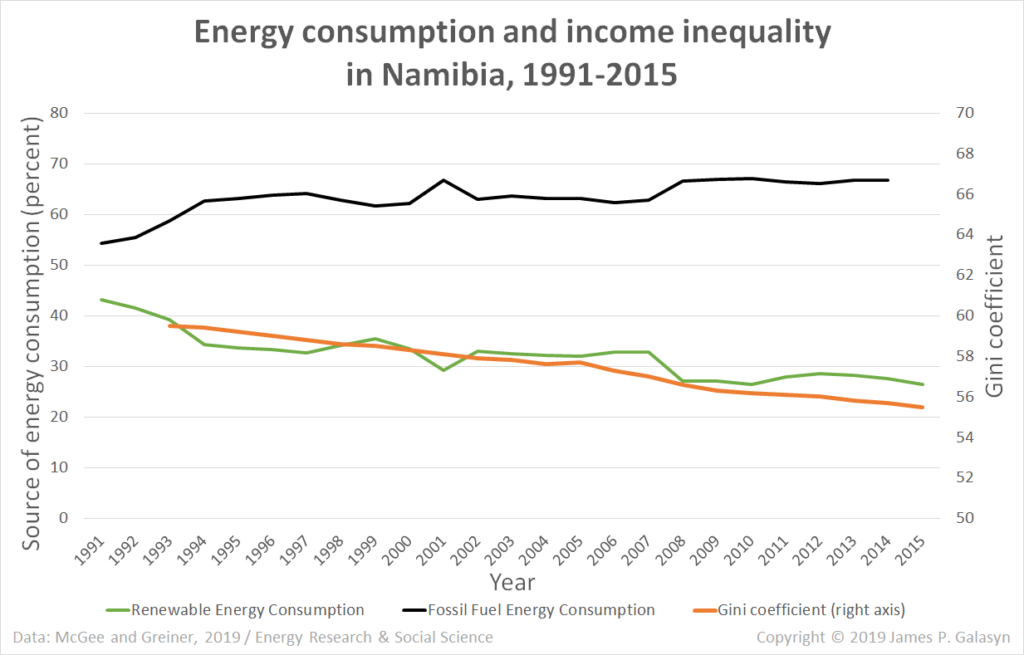

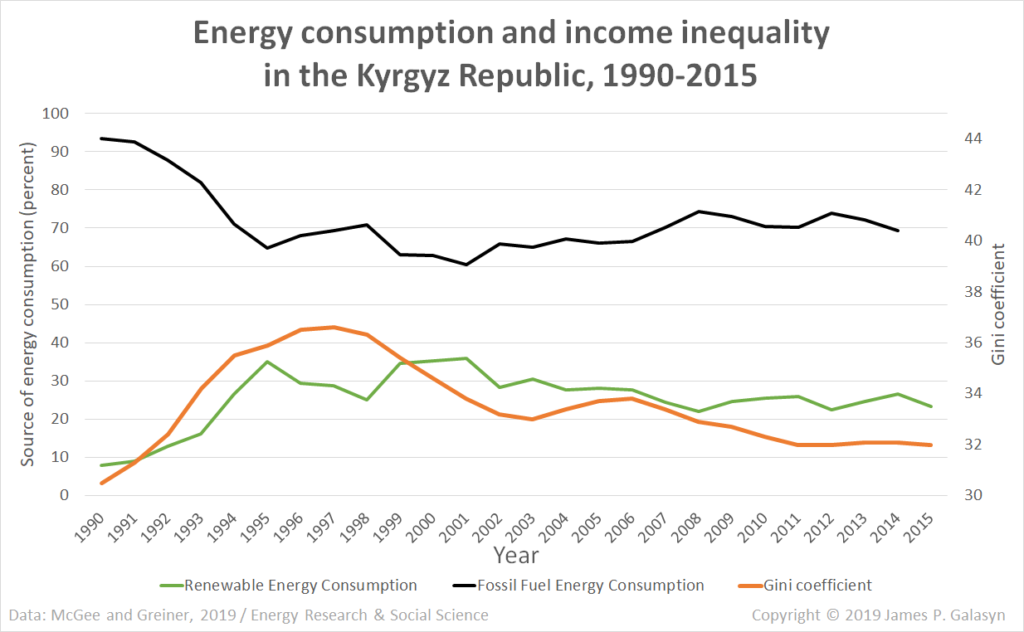

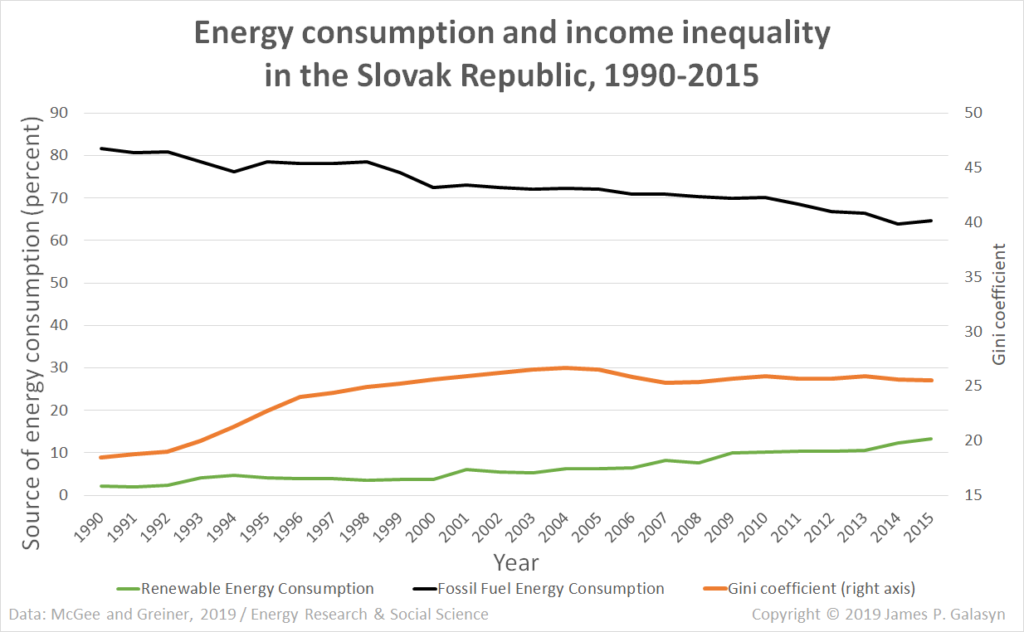

Julius McGee, assistant professor of sociology in PSU’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, and his co-author, Patrick Greiner, an assistant professor of sociology at Vanderbilt University, found in a study of 175 nations from 1990 to 2014 that renewable energy consumption reduces carbon emissions more effectively when it occurs in a context of increasing inequality. Conversely, it reduces emissions to a lesser degree when occurring in a context of decreasing inequality.

Their findings, published recently in the journal Energy Research & Social Science, support previous claims by researchers who argue that renewable energy consumption may be indirectly driving energy poverty. Energy poverty is when a household has no or inadequate access to energy services such as heating, cooling, lighting, and use of appliances due to a combination of factors: low income, increasing utility rates, and inefficient buildings and appliances.

McGee said that in nations like the United States where fossil fuel energy is substituted for renewable energy as a way to reduce carbon emissions, it comes at the cost of increased inequality. That’s because the shift to renewable energy is done through incentives such as tax subsidies. This reduces energy costs for homeowners who can afford to install solar panels or energy-efficient appliances, but it also serves to drive up the prices of fossil fuel energy as utility companies seek to recapture losses. That means increased utility bills for the rest of the customers, and for many low-income families, increased financial pressure, which creates energy poverty.

“People who are just making ends meet and can barely afford their energy bills will make a choice between food and their energy,” McGee said. “We don’t think of energy as a human right when it actually is. The things that consume the most energy in your household — heating, cooling, refrigeration — are the things you absolutely need.”

Alternatively, in poorer nations, renewable sources of electricity have been used to alleviate energy poverty. In rural areas in southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, a solar farm can give an agrarian community access to electricity that historically never had access to energy, McGee said.

“That’s not having any impact on carbon dioxide emissions because those rural communities never used fossil fuels in the first place,” he said.

The study recommends that policymakers consider implementing policy tools that are aimed at both reducing inequality and reducing emissions. McGee and Greiner said such policies would both incentivize the implementation of renewable energy resources, while also protecting the populations that are most vulnerable to energy poverty.

“We really need to think more holistically about how we address renewable energy,” McGee said. “We need to be focusing on addressing concerns around housing and energy poverty before we actually think about addressing climate change within the confines of a consumer sovereignty model.”

Shifts to renewable energy can drive up energy poverty, PSU study finds

Renewable energy injustice: The socio-environmental implications of renewable energy consumption

ABSTRACT: We explore how national income inequality moderates the relationship between renewable energy consumption and CO2 emissions per capita for a sample of 175 nations from 1990 to 2014. We find that, independent of income inequality and other drivers of emissions, increases in renewable energy consumption reduce emissions. However, when national income inequality is considered, we find that as inequality increases renewable energy consumption is associated with a much larger decrease in emissions. We also find that when fossil fuel energy is controlled for, inequality does not significantly moderate the association between renewable energy and emissions. These results suggest that fossil fuel consumption is the main vector through which inequality moderates the relationship between renewable energy and emissions. Drawing on previous work from energy poverty scholars, we theorize that national inequality influences the way renewables are deployed. Specifically, our findings suggest that renewable energy displaces more fossil fuel energy sources when inequality is increasing, while– conversely– fewer existing fossil fuel energy sources are displaced when inequality is decreasing. In additional analyses, we find that as the top 20 percent of income earners’ share of income grows, the association between renewable energy consumption and emissions decreases in magnitude. We conclude by arguing that efforts aimed at increasing renewable energy consumption should adopt policies that ensure the effective displacement of fossil fuels and reduce inequality.

Renewable energy injustice: The socio-environmental implications of renewable energy consumption